The accompanying shiur is available on the Orthodox Union's parsha learning app: All Parsha.

I would have hated myself as a student. Particularly in my late teens and early twenties, I had this incredibly obnoxious quality of only wanting to speak and engage with people who I thought were much more accomplished in areas of Torah learning than myself. That alone is not such a terrible quality. Still, the way it shaped the how I interacted with teachers and friends who did not impress me with their scholarly accomplishments embarrasses me until today. For me, the only rabbi who I could respect transcended any possible accomplishment I could ever reach. I referred to these rabbis as “third-person personalities”—the kind of people who naturally inspired that level of respect, where you felt “third person” in relation to them, not just in the—“Can I ask Rebbe a question?”—way.

During my peak obnoxious period, a rebbe who had any real understanding of my own life and struggles was almost a red flag. I wanted a rebbe who didn’t even know my name, let alone my favorite TV show.

And this to me was the model of rabbinic authority. A towering rabbinic personality who was, so to speak, “the real deal.”

And, based on this week’s parsha, you couldn’t fault me entirely for feeling that way. Our parsha is usually presented as one of the key introductions to the notion of rabbinic authority. If someone has a question in Jewish Law that is not easily addressed, says the Torah, they should go to Jerusalem to inquire how they should proceed:

וּבָאתָ אֶל־הַכֹּהֲנִים הַלְוִיִּם וְאֶל־הַשֹּׁפֵט אֲשֶׁר יִהְיֶה בַּיָּמִים הָהֵם וְדָרַשְׁתָּ וְהִגִּידוּ לְךָ אֵת דְּבַר הַמִּשְׁפָּט׃

And appear before the levitical priests, or the magistrate in charge at the time, and present your problem. When they have announced to you the verdict in the case,

וְעָשִׂיתָ עַל־פִּי הַדָּבָר אֲשֶׁר יַגִּידוּ לְךָ מִן־הַמָּקוֹם הַהוּא אֲשֶׁר יִבְחַר יְהֹוָה וְשָׁמַרְתָּ לַעֲשׂוֹת כְּכֹל אֲשֶׁר יוֹרוּךָ׃

you shall carry out the verdict that is announced to you from that place that God chose, observing scrupulously all their instructions to you.

עַל־פִּי הַתּוֹרָה אֲשֶׁר יוֹרוּךָ וְעַל־הַמִּשְׁפָּט אֲשֶׁר־יֹאמְרוּ לְךָ תַּעֲשֶׂה לֹא תָסוּר מִן־הַדָּבָר אֲשֶׁר־יַגִּידוּ לְךָ יָמִין וּשְׂמֹאל׃

You shall act in accordance with the instructions given you and the ruling handed down to you; you must not deviate from the verdict that they announce to you either to the right or to the left.

For many, including my adolescent self, this became the model for rabbinic authority—an otherworldly rabbi whose rulings you should not deviate from either right or left. As the Sefer HaChinuch famously states, even following the destruction of the Beis Hamikdash and the exile of the central Sanhedrin, we are still commanded to appoint and follow the instructions of our local rabbis. Perhaps so, but why does the Torah emphasize so strongly that these rabbis need to be placed at every gate within the city? Why is it so important to have a rabbi stationed “בכל שעריך”—in every settlement?

Secondly, the Torah describes the authoritative rabbi in a strange way: וְאֶל־הַשֹּׁפֵט אֲשֶׁר יִהְיֶה בַּיָּמִים הָהֵם—the judge who is present in your day.

Umm, no duh?

Obviously, the rabbi has to be present in your day, are you going to go to a rabbi from a different century? The Talmud asks this exact question:

וְאוֹמֵר: ״וּבָאתָ אֶל הַכֹּהֲנִים הַלְוִיִּם וְאֶל הַשֹּׁפֵט אֲשֶׁר יִהְיֶה בַּיָּמִים הָהֵם״, וְכִי תַּעֲלֶה עַל דַּעְתְּךָ שֶׁאָדָם הוֹלֵךְ אֵצֶל הַדַּיָּין שֶׁלֹּא הָיָה בְּיָמָיו? הָא אֵין לְךָ לֵילֵךְ אֶלָּא אֵצֶל שׁוֹפֵט שֶׁבְּיָמָיו. וְאוֹמֵר: ״אַל תֹּאמַר מֶה הָיָה שֶׁהַיָּמִים הָרִאשׁוֹנִים הָיוּ טוֹבִים מֵאֵלֶּה״.

Do you really think that a person can go to a judge who is not alive in his days, the Talmud asks. Instead, the Talmud explains that it specifically mentions the judge within your days as a reminder that you should not compare the leaders of one generation to another. “Do not say,” the Talmud reminds, “How was it that the former days were better than these?” Basically, it is a runner-up prize for the leaders of each generation—they may not be as great or as wise as those from previous generations, but sometimes you just have to make do.

This is an incredibly strange teaching that doesn’t really answer the question. Did the Talmud really think that people just followed leaders from previous generations because they seemed better? Why is this even a concern? A person can only have the guidance that exists in front of them!

To understand this, let’s explore the history of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah, the central rabbinic council of Agudath Israel.

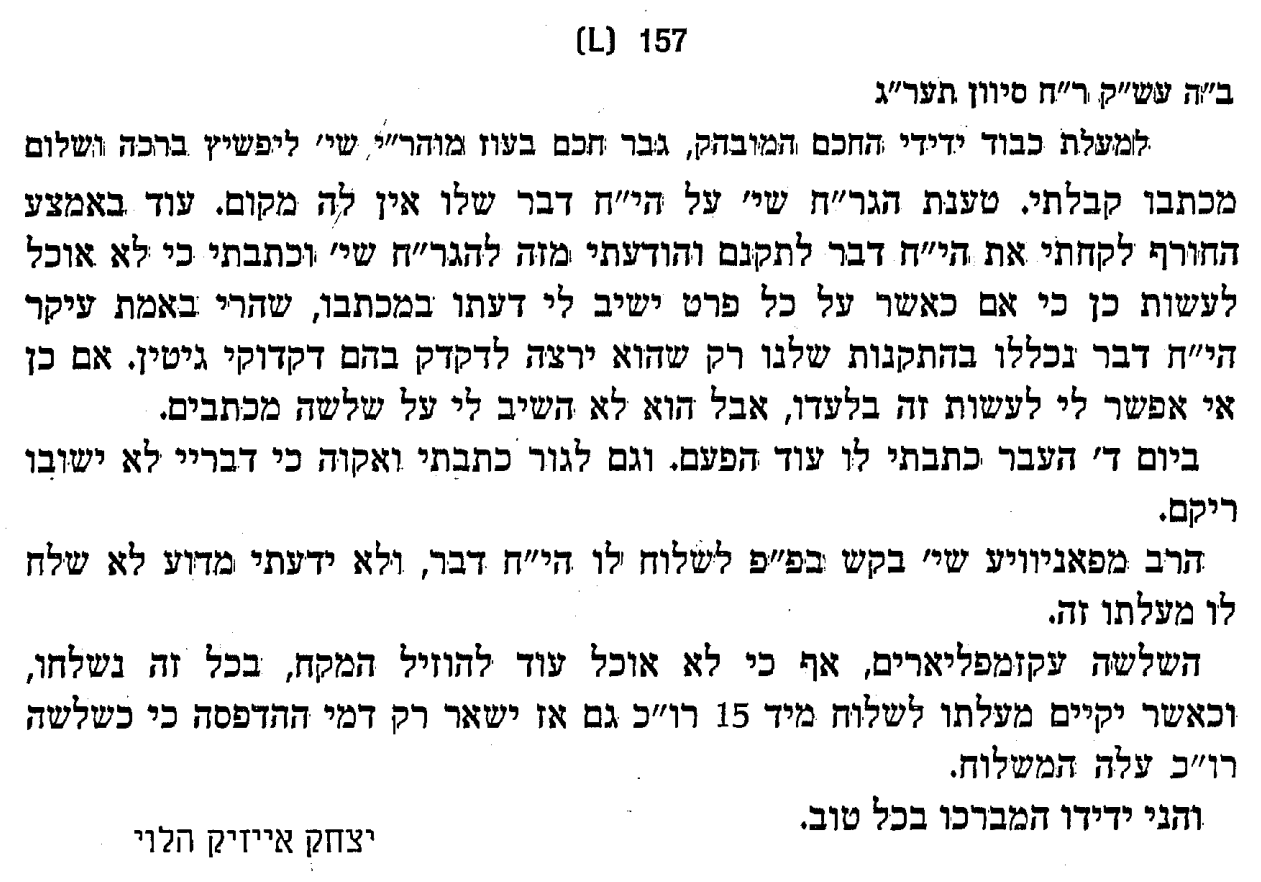

In 1912, in the city of Katowice, Poland, a venerated group of the leading rabbis in the world convened to formally establish Agudath Israel, an organization dedicated to the preservation and development of traditional Jewish life. Due to the invitations being sent out quite late, not every rabbi who was invited was able to attend, including Rav Avraham Yitzchak Kook, who then served as Chief Rabbi of Yaffo. Rabbi Yitzhak Isaac Halevy Rabinowitz, a close friend of Rav Kook, was one of the leaders of the nascent Agudath Israel Movement—his work Doros HaRishonim presents a traditional history of the development of Jewish practice.

To govern Agudath Israel and ensure it would always have rabbinic guidance, they established a central rabbinic governance body that would later be called “Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah,” the Council of Great Torah Sages. Not everyone was thrilled by the name. Rav Yitzchak Halevy much preferred the simpler name, “Vaad HaRabbanim,” (rabbinic council) to the other suggestion “Vaad Gedolei Yisroel,” which he described as like being shot with an arrow when he first heard it. Eventually, it was the term Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah that prevailed—a committee that still operates over a century since its founding.

Rav Yakov Rosenheim, co-founder of Agudath Israel, explained the importance of a Moetzes at the conference:

If “Agudath Yisrael” aims to always be the organized representative of Kelal Yisrael, it has to be led by Da’as Torah…The supreme religious counsel of Agudath Israel has to be a Mo’etses Gedolei Hatorah, a council of the greatest Torah scholars, the luminaries of all lands. Their decision must be the final word whenever practical activity needs to be measured according to the guidelines of the holy Torah and a course of action established.

If only it were so simple.

One of the first issues that arose was the objection of Rav Chaim Soloveitchik, who was revered by all attendees most especially Rabbi Isaac Halevy. Apparently, Rav Chaim Soloveitchik had 18 concerns he wanted to be addressed before moving forward with the proposals of Agudath Israel. Notably, he was concerned with the formation of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah. Initial reports had actually included Rav Chaim as one of the members of the supreme rabbinic council, but he did not end up joining.

What were the 18 concerns of Rav Chaim Soloveitchik?

It is not entirely clear. The letter detailing the concerns was lost according to Rav Yakov Rosenheim.

A great deal of light, however, was shed on this entire episode through the research of my dearest friend Rabbi Yaakov (Jake) Sasson and the greatest wedding present of all time. I happen to be a very difficult person to buy presents for—I genuinely feel blessed that I have everything I could ever want in life. A new book never hurts, but there are not too many gifts that get me excited—though this should not discourage anyone from trying! When I got married my friend, Yaakov Sasson, gave me an incredible wedding present: unpublished research about Rav Moshe Soloveitchik and the family’s issues with the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah.

This research remained unpublished for nearly 5 years at the request of the Soloveitchik family—there were many sordid details from the entire affair that did not reflect well on many rabbis. That was until Moshe Ariel Fus, in a brilliant Hebrew article in Hakira, published nearly all of the available research. Once it had already been published, Rabbi Sasson, then published his own follow-up, filling in some of the details that were missed by Rabbi Fus. Both articles are absolutely fascinating and provide an important window into the differing models of Jewish leadership.

In a 1923 article in Moment, a Yiddish newspaper, Rav Moshe Soloveitchik, eldest son of Rav Chaim, shared more of his father’s concerns and objections, specifically those aimed at the formation of a central rabbinic body, the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah. Jewish leaders are not appointed, argued Rav Moshe. “They became the leaders of the generation without appointment,” Rav Moshe writes, “only through their great source of Torah and wisdom, of which all have been drinking.” According to Rav Moshe Soloveitchik, his father objected to the Moetzes because the entire idea of a central governing body was foreign to the Jewish People—once the Sanhedrin in Jerusalem was disbanded, that was no longer how the Jewish community was run.

In a separate address, Rav Moshe Soloveitchik reiterated his father’s position:

נניח כי אפשר ליצור בזמננו מוסד אוטוריטטי כזה, אבל לזה צריך הסכמת עם ישראל כולו ואינו תלוי ברצון מפלגה...אמנם היו אוטוריטטים לישראל גם בזמנים מאוחרים וגם בזמנים הכי מאוחרים, ושכולנו עוד זוכרים אותם, אבל לא איש שמם הכיר אותם לגדולי תורה והיו בעיניו לאוטוריטטים, אבל לאוטוריטטים. העם ליצור אוטוריטטים מעשה ידי אדם? אוטוריטטים כאלה לא יכיר העם

Let's say that it is even possible to create such an authority in our time, but this requires the consent of the entirety of the Jewish People and does not depend on the will of any party... Indeed, there were appointed authorities of the Jewish people even at very late times as well, but not a single person recognized them as authentic gedolim but rather just as authoritative. To create man-made authorities? Such authorities will not be recognized by the people.

Rav Moshe’s presentation of his father’s position regarding the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah caused quite a stir. Some questioned his biases given his affiliation with Mizrahi, a competing Jewish umbrella organization to Agudath Israel. Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzinski, arguably the most esteemed Torah leader at the time, wrote a strong response to Rav Moshe Solovetichik arguing that Rav Chaim did not have any issues with the notion of a Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah. He even claimed Rav Chaim served as its defacto head!

Rav Chaim’s concerns regarding the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah may never be entirely clear, but it most certainly ushered in a new age of rabbinic authority. A centralized body of appointed leading rabbis clearly conceived Jewish leadership as a top-down hierarchical structure. As my teacher, Rabbi Dr. Ari Bergmann argues in his incredible work, The Formation of the Talmud: Scholarship and Politics in Yitzhak Isaac Halevy’s Dorot Harishonim, Rabbi Isaac Halevy’s conception of the Moetzes closely paralleled his theories regarding the authority of the Talmud itself.

Where does the Talmud derive its authority?

This question, first posed by Rav Yosef Karo in his commentary Kessef Mishnah on Rambam, has two primary approaches. Some, like Rav Isaac Halevy, argued that the Talmud derived its authority from centralized, top-down authority, which he called the Beis HaVa’ad. Similarly, Rav Elchonan Wasserman suggests that the Talmud’s authority is a product of a centralized gathering of all major Torah scholars, which he argues possesses the same authority as the Sanhedrin in Jerusalem, who collectively agreed upon the binding nature of the Talmud. These approaches both emphasize the power of rabbinic authority, paving the way as Professor Lawrence Kaplan argues, for the popularization of the concept of Daas Torah.

Not everyone agreed with this approach. Many took a different stance arguing that the canonization of the Talmud was a function of communal authority rather than rabbinic authority. Meaning, rabbinic authority really derives from the power of the community each respective rabbi represents. It’s not about finding the biggest rabbi, it is about finding the rabbi with the most widespread acceptance. It is not the rabbis who wield power, it is the community that through its acceptance of Torah text—which is accomplished through students, subsequent commentaries, and actual mass adoption—canonizes its power. Yes, Rav Moshe Feinstein was a great rabbi, one of our greatest, but there have been many great rabbis who never achieved the widespread acceptance of Rav Moshe. What distinguishes Rav Moshe—and really any authoritative text or opinion—is its adoption by the Jewish community. This approach, which is articulated by Rav Moshe Soloveitchik, Rav Kook, and later by Rav Shlomo Fischer, emphasizes communal authority as the primary vehicle of both Talmudic authority and ongoing rabbinic power.

Interestingly, when Rav Moshe Feinstein, who served as the chairman of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah in the United States of America, was interviewed by the New York Times, he articulated the source of his own authority more in line with Rav Moshe Soloveitchik than with the actual vision of Agudath Israel. “You can’t wake up in the morning and decide you’re an expert on answers,'“ Rav Moshe explained to The Times, “If people see that one answer is good, and another answer is good, gradually you will be accepted.”

(It is just important to note that this argument should not be marshaled to advance non-Orthodox views, given by sheer numbers they are, so to speak, the most widely accepted movement. Ignorance is not acceptance. Acceptance is an active choice made by members of the halachic community—who aim to preserve the binding status of halacha—to adopt a particular view. Just because most Jews don’t keep Shabbos does not make violating Shabbos permissible. Acceptance is a function of educated practice. No opinion or practice persists without the community that sustains it.)

Different conceptions of Talmudic authority yield very different visions of contemporary rabbinic authority. Is it top-down—like Rav Yitzchak Isaac Halevy and the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah—or is it bottom-up—like Rav Moshe Soloveitchik, Rav Kook, Rav Shlomo Fischer?

As Rabbi Dr. Ari Bergmann explains in his book:

From Halevy’s perspective, the supreme authority of Mo’etses Gedolei Hatorah was well-grounded in theory and tradition. More specifically, the talmudic beit hava’ad imagined by Halevy was the ideal historical precedent for a rabbinic conclave modeled after the Sanhedrin. The Sanhedrin’s authority extended beyond halakhic rulings to include such communal decisions as the appointment of the king, the choice to go to war, and the expansion of the city of Jerusalem. According to Halevy, the beit hava’ad and the Mo’etses Gedolei Hatorah possessed similar authority. Furthermore, just as the decisions of the Sanhedrin could not be contradicted, and any elder who did so would be deemed a rebellious elder [zaken mamre], the Agudah-affiliated Mo’etses Gedolei Hatorah held ultimate sway. Rabbi Wasserman, who explained the authority of the Babylonian Talmud in precisely such terms, as discussed in chapter 3, was one of the main proponents of the Da’as Torah of Mo’etses Gedolei Hatorah and was perhaps the most articulate spokesman for the Agudah ideology of the interwar period. Halevy’s international conclave of rabbinic authorities thus came to be the centerpiece of Agudath Israel and conferred upon it authority and pedigree.

And that brings us back to our parsha.

Why is there such an emphasis that you must go to the judges within your days? As if it would be possible to go to anyone else. Is this just some runner-up prize for later generations so they don’t look with disdain at their loser rabbis? C’mon, we’re not all so bad!

Instead, the emphasis on judges specifically within your days centralizes the communal role from which all rabbinic authority ultimately derives. It is not enough to just have incredible rabbis and brilliant leaders—they must also reflect the needs and character of the generation they serve. Every generation needs its own style and approach to Jewish leadership because each generation is unique and it is within the acceptance of each generation that rabbinic authority ultimately derives.

It is not just about rabbinic authority, it is about communal authority—the Jewish People ultimately decide how it will be preserved, if at all.

A similar formulation can be found in the responsa Bnei Banim of Rav Yehuda Henkin:

המלצתי עליו הכתוב "ובאת אל הכהנים הלוים ואל השפט אשר יהיה בימים ההם". ידועה שאלת הגמרא, וכי תעלה על דעתך שאדם הולך אצל הדיין שלא היה בימיו? ועוד יש לדייק שהיתה לתורה לאמר ואל השופט אשר בימים ההם, ולמה כתבה "יהיה" שהיא מלה יתרה? אלא יש שופט שחי בדור ואינו מאותו הדור כי אינו מכיר מצבו ובעיותיו, ולכן באבות אמרו אל תדין את חברך עד שתגיע למקומו, מקומו דוקא, שתבקר שם ותראה איך נתגדל ומהי המציאות, - וכן הרבה מצאנו מקומו שפרושו מקום דוקא וכמו במקום שבעלי תשובה עומדים אין צדיקים גמורים יכולים לעמוד שפרשוהו במחיצה בגן עדן, וגם על הארץ בעלי תשובה עומדים בצדקתם בסביבה שצדיקים גמורים היו נטמאים שם. - וזהו שאמר הכתוב ובאת אל השופט אשר יהיה בימים ההם, שמצוה לבוא לשופט המכיר תנאי הימים, ואולם היא גם מצוה על השופט להכיר תנאי הימים ואם לאו אל יורה וזהו אשר יהיה בימים ההם שהמלה "יהיה" מצוה על השופט. ורבנו הגמו"ז זצלה"ה היה שופט מימיו ומימינו והכיר בין ביהודים ובין בעולם הרחב, ואת כל תנאי הדור.

We are commanded to go to the judge of our time because we need leaders who understand and appreciate the unique challenges and opportunities of each generation.

Commenting on this very verse, the Talmud says: יפתח בדורו כשמואל בדורו, Yiftach within his generation is like Shmuel of his generation. Presumably, like the plain meaning of the verse, the Talmud is basically giving a runner-up comfort trophy to Yiftach. Look, you’re no Shmuel, but each generation has to take what they can get.

וזהו יפתח בדורו כשמואל בדורו (ראש השנה כ"ה ע"ב) ששמעתי בשם ר"ב קדוש ז"ל דרצה לומר מי שפותח שער חדש בעבודת השם יתברך בדורו הוא המנהיג האמיתי כשמואל בדורו, דבכל דור יש התחדשות ופתיחתו הוא על ידי מנהיג הדור

Rav Tzadok has a beautiful interpretation of this Talmud passage. Yiftach is not a noun referring to the Prophet, it is a verb. Yiftach, meaning someone who is פותח, who opens up new doorways, new entry points for the service of God is the true leader, like Shmuel, of their generation. And each generation needs its own unique doorway.

Shabbos Reads — Books/Articles Mentioned

The Formation of the Talmud: Scholarship and Politics in Yitzhak Isaac Halevy’s Dorot Harishonim, Ari Bergmann

The Politics of Torah: The Jewish Political Tradition and the Founding of Agudat Israel, Alan L. Mittelman

Responsa: The Law as Seen By Rabbis for 1,000 Years, Israel Shenker

הרב משה הלוי סולובייצ'יק ומאבקיו ב"מועצת גדולי התורה" ו"אגודת הרבנים" בפולין, משה אריאל פוס

השלמות למאמר: הרב משה הלוי סולובייצ'יק ומאבקיו במועצת גדולי התורה ואגודת הרבנים בפולין, יעקב ששון

Daas Torah: A Modern Conception of Rabbinic Authority, Lawrence Kaplan

Check out All Parsha, where you can find weekly audio of Reading Jewish History in the Parsha, as well as other incredible presenters and amazing features that will enhance your Parsha journey!

Reading Jewish History in the Parsha has been generously sponsored by my dearest friends Janet and Lior Hod and family with immense gratitude to Hashem.