The accompanying shiur is available on the Orthodox Union's parsha learning app: All Parsha.

I'm trying to remember the first couple I ever heard of getting divorced. As a child, it was a jarring piece of news. Wait, not all marriages last forever? Suddenly, you start paying a little closer attention to how your parents speak to each other—quietly gauging if your own family might come undone too.

I've always been oddly fascinated by divorce. My favorite tractate of Talmud? You guessed it—Tractate Gittin, the one all about divorce. Trust me, my wife didn't find it very charming when I told her. Thankfully, we're happily married.

:)

Even now, whenever I hear about a couple getting divorced, I can’t help but feel curious. I wonder: Why? When did they first know? Could it have lasted if they had tried harder?

I don't ask these questions out loud, and I don’t gossip to find the answers, but I'd be lying if I said they weren’t on my mind. They're compelling questions because the nature of romantic relationships and commitment is so mysterious—and so central to our sense of self.

The mystery of divorce truly begins with its presentation in the Torah.

In the beginning of the 24th chapter of Sefer Devarim we are presented with the source for divorce in the Torah:

כִּי־יִקַּח אִישׁ אִשָּׁה וּבְעָלָהּ וְהָיָה אִם־לֹא תִמְצָא־חֵן בְּעֵינָיו כִּי־מָצָא בָהּ עֶרְוַת דָּבָר וְכָתַב לָהּ סֵפֶר כְּרִיתֻת וְנָתַן בְּיָדָהּ וְשִׁלְּחָהּ מִבֵּיתוֹ׃

A man takes a woman [into his household as his wife] and becomes her husband. She fails to please him because he finds something obnoxious about her, and he writes her a bill of divorcement, hands it to her, and sends her away from his house

וְיָצְאָה מִבֵּיתוֹ וְהָלְכָה וְהָיְתָה לְאִישׁ־אַחֵר׃

And she leaves his household and becomes [the wife] of another man

The way that the laws of marriage and divorce are portrayed seems almost backward. The Torah spends a great deal of time detailing the laws of divorce but barely says a word about the details of actual marriage. In fact, many laws of marriage are learned from the laws of divorce! That seems ominous.

A principle throughout the Talmud’s discussion of the laws of marriage and divorce is that marriage laws are derived from divorce because of the juxtaposition of the Torah’s description of the dissolution of the marriage (ויצאה) and the creation of a new marital bond following the divorce (והיתה). The Talmud calls this מקיש הויה ליציאה — connecting the “becoming” of marriage to the “leaving” of divorce.

In one incident in the Talmud, Reish Lakish literally screams at the top of his lungs like a squawking bird, “We must juxtapose the laws of divorce to the laws of marriage!”

Why is divorce presented in such a strange way in the Torah? And why do we rely on divorce to derive so many of the laws of marriage? It almost feels like divorce is the main event, while the details of marriage itself are left so unarticulated in the Torah and the Talmud.

To understand the significance of Jewish divorce and marriage, let’s explore some of the most famous divorces in Jewish history.

Sadly, Jewish history is filled with many divorces. Many notable rabbis had marriages that did not work out. There are two divorces, however, that have rightfully received an unusual amount of attention from scholars of Jewish history—and only one of them involves a Jew!

Henry VIII

One of the most famous divorces in Jewish history was not even a Jewish divorce. In fact, it created a new church!

Henry VIII was married to Catherine of Aragon (her parents Ferdinand and Isabella expelled the Jews of Spain in 1492), but the marriage did not produce a male heir for the throne, so Henry sought a divorce.

Interestingly, Catholics are generally not permitted to divorce because the Catholic Church believes that marriage is a sacrament, a lifelong covenant that mirrors the relationship between Christ and the Church. According to Catholic teaching, marriage is indissoluble once it is validly entered into. This belief is rooted in Christian scripture, especially in Jesus’ words in the Gospel of Matthew: "What therefore God has joined together, let no man separate" (Matthew 19:6).

But Henry had a plan. He wanted to marry a member of the Queen’s entourage named Anne Boleyn—a figure I first heard about from the Blue’s Traveler’s song Hook. The only way he could end his marriage with Catherine was with an annulment from Pope Clement VII. When Pope Clement VII refused to grant the annulment, citing that the marriage was valid, Henry had to find another way to annul his marriage to Catherine.

One of Henry’s advisors introduced him to Oxford Hebraist Robert Wakefield, who had a solid command of rabbinic sources. Wakefield devised an argument based on Talmudic sources that would render his marriage to Catherine null and void. Essentially, Henry wanted to argue that his marriage to Catherine was never binding because she was previously married to his brother—seemingly a violation of the Biblical prohibition of marrying your brother’s spouse mentioned in Leviticus 18:16. Of course, the laws of yibum, Leverite marriage, make this far more complicated because there are circumstances where there is an outright commandment to marry a brother’s spouse as is mentioned in our parsha (Deut. 25:5).

There were no Jews left in England for Henry to consult since all of the Jews were expelled in 1290. So his advisors traveled to Venice to figure out if, in fact, the laws of yibum were still binding. The response he got was from Jacob Rafael of Modena, who sided with the Church’s original opinion that the marriage could not be annulled.

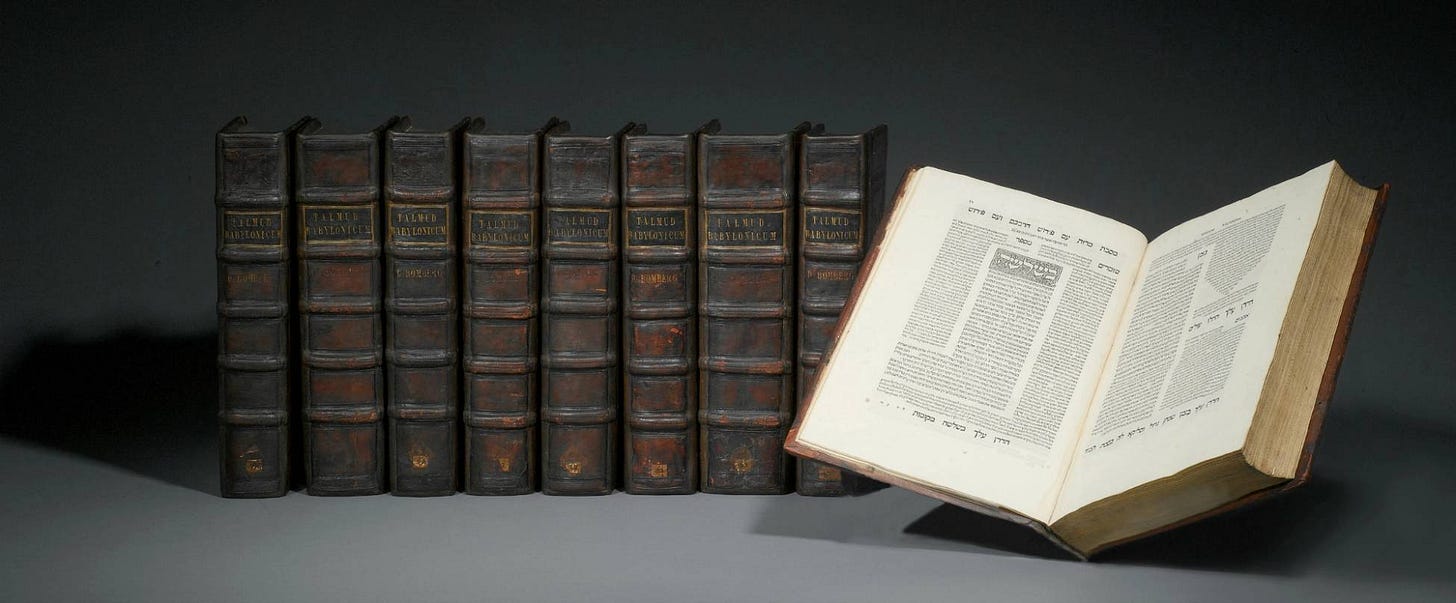

It was during this time, that Henry VIII purchased the nine-volume set of Talmud published by Daniel Bomberg, which had been completed just a few years prior in 1523. Without a clear path to annulment from the Church, the Italian rabbinate, or the Talmud, Henry VIII did the next best thing: He started his own Church. Henry broke from the Catholic Church, declaring himself the head of the Church of England through the Act of Supremacy in 1534. This allowed him to annul his own marriage and led to the English Reformation, separating England from the authority of the pope.

An interesting postscript to this story is how the Bomberg Talmud, originally purchased on behalf of Henry VIII, ended up in the hands of the famed Jewish bibliophile Jack Lunzer. Lunzer spent nearly his entire career as a book collector searching for a complete set of the original Bomberg Talmud. Eventually, he acquired the very Talmud that had been bought for Henry VIII—a piece that became the crown jewel of his collection, known as the Valmadonna Trust.

It is one of the most remarkable stories in the history of book collecting.

And as Dr. Jeremy Brown retells:

In the 1950s there was an exhibition in London to commemorate the readmission of the Jews to England under Cromwell. Lunzer noted that one of the books on display, from the collection of Westminster Abbey, was improperly labelled, and was in fact a volume of a Bomberg Talmud. Lunzer called the Abbey the next day, told them of his discovery, and suggested that he send some workers to clean the rest of the undisturbed volumes. They discovered a complete Bomberg Talmud in pristine condition, and Lunzer wanted it. But despite years of negotiations with the Abbey, Lunzer's attempts to buy the Talmud were rebuffed.

Then in April 1980, Lunzer's luck changed. He read in a brief newspaper article that the original 1065 Charter of Westminster Abbey had been purchased by an American at auction, but because of its cultural significance the British Government were refusing to grant an export license. Lunzer called the Abbey, was invited for tea, and a gentleman's agreement was struck. He purchased the Charter from the American, presented it to the Abbey, and at a ceremony in the Jerusalem Chamber of Westminster Abbey the nine volumes of Bomberg's Babylonian Talmud were presented to the Valmadonna Trust.

You can hear Jack Lunzer tell the entire story here:

Cleves Get

Like many, I first heard about the story of the Cleves Get from Rabbi Dr. Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff. Aside from being one of the great scholars and raconteurs of Jewish history, his MA thesis was about the divorce in Cleves. As he recounts, he got the idea for studying this chapter of Jewish history from his rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, who had mentioned that it would make a superb thesis.

On a Tuesday in 1766, the 8th of Elul, Isaac the son of Lazer Newburg from Mannheim, Prussia got married to Leah, the daughter of Jacob Gunzhausen of Bonn, Prussia. “This inconspicuous event,” as Rabbi Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff explains, “later developed into the cause celebre of responsa literature of this period.” Nearly every major rabbi weighed in on the controversy that would soon unfold.

On the Shabbos before the wedding Isaac already began exhibiting some strange behaviors—he looked depressed and would manically pace back and forth. Despite inquiries from Leah’s parents, Isaac insisted he was fine and the wedding went off without a hitch.

Things began to really spiral the Shabbos after the wedding. Isaac took the dowry money and without informing anyone—including his new wife Leah—fled. He was later found living on a farm run by a non-Jew, claiming he had run away to escape government persecution. There were a few other flare-ups early on in the marriage—when a waitress intimated to Isaac that she had heard the story of him fleeing, he became hysterical all over again. Isaac kept on insisting he was persecuted but could not provide any concrete details.

Eventually, Isaac decided that the only way forward was divorce. He planned to flee to England afterward, and he chose the Rabbinical Court in the town of Cleves—conveniently on his escape route—to administer the proceedings. Isaac appeared before the Beis Din, answering all their questions satisfactorily. The marriage ended, but the controversy was just beginning.

Isaac's parents were not present for the divorce proceedings. In fact, Isaac hadn’t even told them he was getting divorced. When they found out, they were outraged, immediately assuming that Leah’s parents had orchestrated the divorce so she could claim half of the marriage assets. Isaac’s father then approached the head of the Rabbinical Court in Mannheim to have the Cleves divorce annulled. The Mannheim Beis Din formally petitioned the more prestigious Frankfurt Beis Din to nullify the divorce between Isaac and Leah that had been executed in Cleves.

The question at hand was whether or not Isaac was mentally competent enough at the time of the divorce for the proceedings to have halakhic validity. On the one side was the rabbi in Cleves, Rabbi Israel Lipschutz, who felt Isaac was of sound mind at the time of the divorce. The Frankfort Beis Din however annulled that divorce on the basis that Isaac’s earlier erratic behavior was a clear indication that he was not completely of sound enough mind to execute a divorce.

Soon enough more and more rabbis began to weigh in. Rav Yaakov Emden, who had achieved renown for his battles against the Sabbateans, ruled that the divorce was completely valid. Other rabbinic luminaries weighed in as well, most assuming that the divorce was valid. Rav Aryeh Loeb of Metz, known as the Shaagas Aryeh—the title of his responsa, also declared the divorce valid. Rav Ezekial Landau, known as the Nodeh B’Yehudah, penned a lengthy responsa, accussing the Frankfort Beis Din of being unnecessarily stubborn in their refusal to reconsider their annulment of the divorce.

The involvement of the Nodeh B’Yehudah infuriated the Frankfurt Beis Din, led by Rabbi Avraham Abush. They issued a sort of cherem, declaring that anyone who opposed their ruling and annulled the divorce would be barred from holding any position in the community.

A divorce between two relative unknowns ended up embroiling the entire rabbinate.

Rabbi Rakeffet adds an interesting postscript to the entire incident:

As a final tribute of respect and love for their departed Rabbi, the Frankfort Jewish Community resolved to engage no successer to Rabbi Abraham Abush who validated the divorce issued in Cleves. Finally, in 1772, Rabbi Pinchas Halevi Ish Horowitz (known as the Hafl’ah) was chosen as the successor to Rabbi Abraham Abush, because he had never issued any responsa validating the divorce.

In a post-script to that post-script, Rabbi Rakeffet notes that Rabbi Horowitz did in fact pen an entire responsa on the topic that argued with Rabbi Abush and validated the divorce, but ink spilled all over the finished responsa. He was convinced by another Rabbi present not to bother re-writing it.

Perhaps the most fascinating part of the tale is what happened to Isaac and Leah. According to one account, as cited by Rabbi Pinner Dunner in his marvelous account of the Get of Cleves in his utterly fascinating book Mavericks, Mystics & False Messiahs, they eventually reconciled. They had abided by the Frankfort decision that the divorce was annulled, so neither had dated anyone else. When they eventually remarried, just to be sure, Isaac said to Leah, “את עוד מקודשת לי בטבעת זו כדת משה וישראל” — “You remain betrothed to me.”

And this brings us back to our parsha and the unique approach of the Torah to marriage and divorce.

My dear friend and colleague, the ever-brilliant, Rabbi Itamar Rosensweig, has a powerful approach to the Torah’s conception of divorce. Divorce, argues Rav Itamar in a deeply sourced Hebrew article, is what allows us to preserve an idealized form of marriage. A marriage should be a spiritual loving union and a marriage that is filled with fighting, jealousy, and negativity undermines the very point and purpose of the Jewish of marriage. Divorce preserves the sanctity and purity of marriage.

Unlike Christianity, which views divorce as a final severance, Judaism not only recognizes divorce but sanctifies it. This highlights a fundamental difference in how Christianity and Judaism perceive exile. The destruction of the Temple and our current exile are often compared to a divorce. As Rav Tzadok points out, all the narratives about the Temple's destruction are found in Tractate Gittin, which deals with divorce. For Christianity, the Temple’s destruction was seen as a definitive sign that God had irrevocably ended His covenant with the Jewish people. In contrast, Judaism sanctifies both absence and exile, understanding that even in separation, divinity can still dwell. Divorce, in this sense, preserves the sanctity of the idealized relationship—one we continue to hope will be restored.

Divorce then is not just another commandment, but a central part of the Jewish conception of relationships themselves. In order to preserve the sancitity of our relationships we also must have a sanctified process to dissolve them. When absence serves a holy purpose, it is sanctified as well. When Rabbeinu Tam, of the most prolific Baalei Tosafos was asked about writing a name of a idol in a gett (a Jewish divorce document), he cried out, “God forbid to mention the name of an idol in the Torah of Moshe and Yisrael.” Divorce is more than a contractual agreement, just as marriage is more than a mere acquisition. It touches on the very essence of the Jewish concept of intimacy. Perhaps this is why divorces provoke such controversy and response, as seen in Cleves. In any case, we continue to pray for God to reunite with the Jewish people and bring us the comfort we so deeply need, “את עוד מקודשת לי בטבעת זו כדת משה וישראל” — “You, the Jewish People, remain my betrothed.”

Shabbos Reads — Books/Articles Mentioned

The Greatest Story in the Annals of Book Collecting, Jeremy Brown

Henry VIII, Oxford’s Hebraists and the Rabbis of Venice in the 16th Century, Eli

Yevamot Interlude: Henry VIII, Yevamot, and the Sotheby’s Auction, Jeremy Brown

The Divorce in Cleves, 1766, Arnold Rothkoff

Mavericks, Mystics & False Messiahs: Episodes from the Margins of Jewish History, Pinni Dunner

Mitzvas Geirushin [Hebrew], Itamar Rosensweig

Check out All Parsha, where you can find weekly audio of Reading Jewish History in the Parsha, as well as other incredible presenters and amazing features that will enhance your Parsha journey!

Reading Jewish History in the Parsha has been generously sponsored by my dearest friends Janet and Lior Hod and family with immense gratitude to Hashem.

Great article! I finally understand a bit of your obsession with Gittin

Sorry to spoil a good story, but after a flurry of excitement when Jack Lunzer first acquired the Talmud - indeed a marvelous story!- it was determined that the Talmud belonged/was bought by an Oxford Professor of Hebrew, Richard Brauerne. When Sothebys sold the Talmud, their brochure didn’t mention Henry!