Leadership in Crisis and in Absence

On Parshas Tetzaveh, Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzinski, and Moshe's missing name

The accompanying shiur is available on the Orthodox Union's parsha learning app: All Parsha.

It’s always curious what parsha ideas from your youth stay with you.

One of the earliest parsha ideas I remember—I’m still not sure why this has become an elementary school Rebbe favorite—is that this is the only parsha since the introduction of Moshe Rabbeinu that does not contain his name. Well, sort of. Moshe speaks Sefer Devarim in first person, so there are parshiyot where he is absent there as well. But still, this fact, which my Rebbe taught me around 30 years ago, has always stayed with me.

And maybe it is because I learned this when I was so young that I never really explored why this makes any sense.

The reason why Moshe’s name does not appear, as my Rebbe explained, is because Moshe, during the chet ha’egel, the sin of the Golden Calf, asked God to erase his name from the Torah if God does not forgive the Jewish People.

“מְחֵנִי נָא מִסִּפְרְךָ אֲשֶׁר כָּתָבְתָּ,” Moshe tells God—erase me from your book!

It is because of this statement, explains the Baal HaTurim in the introduction to Parshas Tetzaveh, that Moshe’s name is missing in our parsha.

But this leaves me with even more questions.

Is Moshe being punished for his willingness to sacrifice his legacy on behalf of the Jewish people? Just because he said these words, his name is being erased?! He was trying to help the Jewish People to preserve our collective legacy!

And secondly, even more strange, why this parsha? Even if his name should have been erased why specifically in Parshas Tetzaveh which actually comes before Parshas Ki Sisa, when Moshe actually says this to God? It seems pretty arbitrary.

And yes, there are some very clever allusions explaining that Moshe’s name really is in the parsha. Ben Ish Chai writes that Moshe’s plea to be erased from the Torah—מספרך—should be read as מספר כ', from the 20th parsha in the Torah, namely Tetzaveh. Other more intricate uses of gematria find allusions to Moshe’s name as well. The Vilna Gaon explains that if you spell out each letter of Moshe’s name (מם שין הא) the letters not represented in the actual name (ם ין א) equals 101, the same number of verses in Parshas Tetzaveh. Both are nice allusions but neither fully explain the significance of Moshe’s absence from our parsha in particular.

To understand Moshe’s leadership and the relationship to this parsha, let’s explore the leadership of Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzinski during times of crisis.

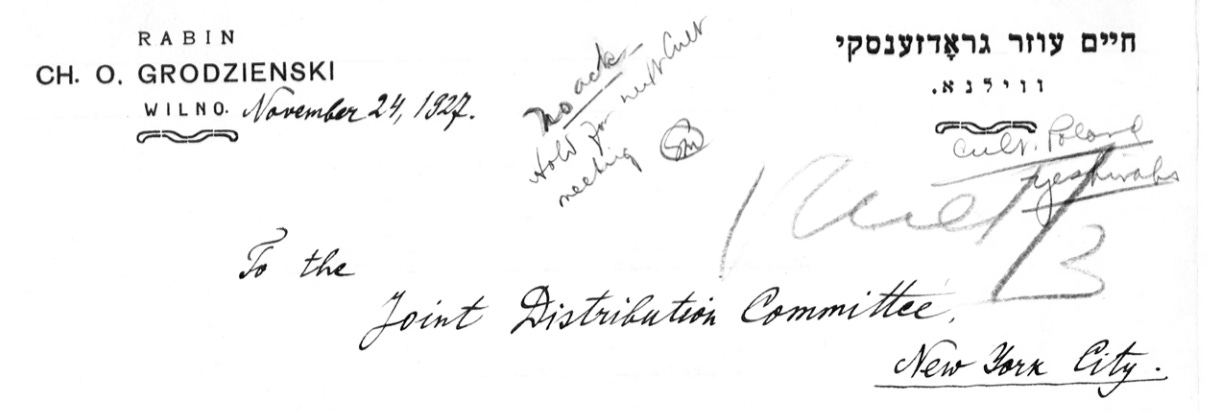

Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzinski (1863-1940) was one of the most universally recognized leaders of the Jewish People. Even among other greats, he was distinguished for his leadership, particularly in times of crisis, leading much of the efforts to save European Jewry from the Holocaust.

His early life, however, was steeped in Torah study. Rav Chaim Ozer, as he is affectionally called, was distinguished as a Torah genius from a very young age. At his Bar Mitzvah, he reportedly regaled the audience by being able to finish any line from the dense commentary Ketzos haChoshen that anyone mentioned.

Honestly, this kind of story never did much for me. There have been many geniuses throughout Jewish history and that is not, in my opinion, why certain rabbinic personalities are preserved more than others. What distinguished Rav Chaim Ozer was undoubtedly that his Torah genius was combined with compassionate leadership for the Jewish People.

There have been several biographies and articles written about his life, though I think the best is Rabbi Dovid Kaminesky’s Hebrew work entitled Raban Shel Kol Bnei HaGoleh, though only the first volume focusing on his early years has been published. A shorter but excellent overview of his life was written by Rabbi Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff in the first volume of his work Rakafot Aharon.

There is a subtle irony in writing history about Rav Chaim Ozer’s life since he himself, in his approbation to Rav Yehuda Lifschutz’s historical work, Dor Yesharim, expressed hesitance with the study of history. Rav Chaim Ozer writes (see his collected letters #293):

Historically, gedolei torah never devoted their minds to delving into Jewish history or even to write books about Jewish sages of past generations. The words of our ancient and later rabbis are alive and maintained in the mouths of those who learn torah. Every study hall is brimming with rabbis and their students studying a living torah as if the words were taught that day. There is no need to memorialize tzadikim, as their words are their legacy.

However, since the decline of Judaism in Europe during the time of the Reform… there is no torah and there is no fear of God. As such, the remaining authors devoted themselves to memorialize the great figures and occurrences of past generations. Some of them intended to endear the wisdom of Israel and its gedolim to this generation. If they won’t receive this through knowledge, recognition, and vision (i.e. through learning torah), at least they should receive it through hearing stories – that they had outstanding ancestors through which they claim honor.

(Translation is from Rabbi Jonah Steinmetz’s fantastic review of Rabbi Dovid Kaminetsky’s biography)

Rav Chaim Ozer expressed similar ambivalence to the study of Jewish History when he was approached by a group of American Rabbis who wanted to know if it was appropriate to participate in the celebrations of Rambam’s 800th birthday. “Such celebrations are strange,” Rav Chaim Ozer responded (letter #306), “Rambam continues to live within the mouth of rabbonim and their students.”

Rav Chaim Ozer did not have an easy life. His first engagement, to the daughter of Rav Eliyahu Feinstein of Pruzhin, was broken off. Rav Eliyahu Feinstein was Rav Moshe Feinstein’s uncle and also the father-in-law of Rav Moshe Soloveitchik. It is not entirely clear why the shidduch was abandoned, though it seemingly weighed heavily on Rav Chaim Ozer throughout his life. The woman he was supposed to marry ended up marrying Rav Menachem Krakowski, who was later selected by Rav Chaim Ozer, to sit together with him on the Vilna Beis Din. Rav Chaim Ozer ended up marrying the granddaughter of Rav Yisroel Salanter, founder of the mussar movement. Sadly, the only child from the marriage predeceased him and did not have any children of her own.

Following the death of Rav Yitzchak Elchanan Spektor in 1896, Rav Chaim Ozer gradually moved into the center of leadership within the Jewish community. He was never formally appointed Chief Rabbi of Vilna, in deference to the old custom of not having a formal Chief Rabbi of Vilna. Even after a different rabbi, Rabbi Rubenstein was appointed to the formal government position, Rav Chaim Ozer remained the center of gravity in Vilna and gradually for all of world Jewry. This dispute created a wedge in the community and was later the inspiration for Chaim Grade’s book Rabbis and Wives.

Rav Chaim Ozer’s leadership was global and local, the highest level of scholarship coupled with deep empathy and concern for the Jewish People. In one moving story, recounted by Rabbi Rakeffet, a young couple approached Rav Chaim Ozer for a blessing before their wedding and mentioned in passing that they didn’t have any relatives nearby. Rav Chaim Ozer, knowing the kallah (bride) didn’t have anyone to teach her the laws of family purity, immediately offered to teach her these laws himself. “Do not be ashamed,” Rav Chaim Ozer told her, “that you don’t know these laws—they are the basis of Jewish family life but you don’t have family nearby to teach you, so I will.”

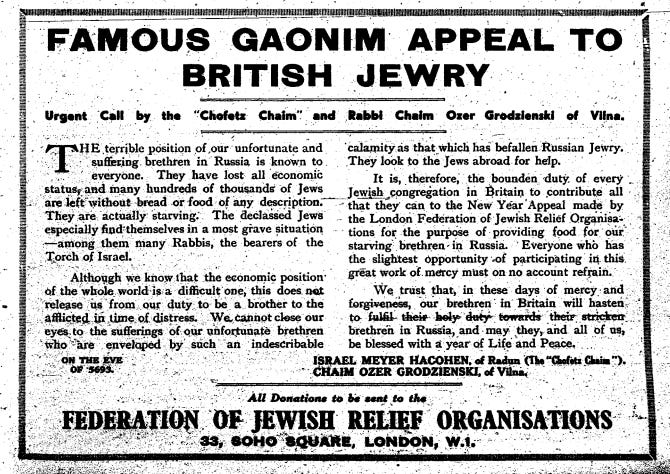

He also led global movements—he was instrumental in the founding of Agudath Israel and coordinated aid efforts during WWI and in 1924, along with the Chofetz Chaim, established the Vaad HaYeshivos providing financial support for Torah students throughout Europe.

Nothing, however, could prepare world Jewry for the horrors to come.

In 1932, a year before the formal rise of Nazi Germany, Rav Chaim Ozer was already overwhelmed and somewhat concerned about what the future had in store for European Jewry. He wrote the following letter (vol. 1 #20) to his nephew—the translation is again from Rabbi Jonah Steinmetz’s fantastic review of Rabbi Dovid Kaminetsky’s Rav Chaim Ozer biography:

Thank God we and our family are well. However, there is no shortage of burdens and aggravation. There is a decline in the physical and spiritual condition, causing many people to come to discuss and pour their bitter hearts out, and it is upon me to listen to their sighs all day. The institutions are on the verge of closure (lit. hang on nothingness), the Rameilles Yeshiva which is my load has no foundation or basis, and the future is covered in fog.

In 1939, Hitler invaded Poland, and Yeshiva students throughout Europe found refuge in Vilna. Rav Chaim Ozer made sure all of the Torah students were cared for and directed each synagogue in Vilna to care for the Yeshiva students. So many students had come to Vilna for refuge that the Lithuanian government asked Rav Chaim Ozer to coordinate places for them in other parts of the country, which he agreed to. As Ben-Tsiyon Klibansky painstakingly details in his book, The Golden Age of Lithuanian Yeshivas, towns sent emissaries to Vilna and vied to host the yeshiva students. The towns fought among themselves for who would have the privilege of hosting the yeshivas that were then crowded in Vilna.

As the situation in Europe began to deteriorate rapidly, so did the health of Rav Chaim Ozer, who placed the burden of coordinating all of the war refugee efforts on his shoulders. He was in touch with rabbis throughout the world, including the United States, most notably Rabbi Leo Jung and Rabbi Eliezer Silver. Throughout this time, Rav Chaim Ozer did not stop answering halachic questions—the final volume of his responsa, Achiezer, was published in 1939. The haunting introduction addresses why Torah should even be published during a time of such crisis:

Is a time of crisis an appropriate time to be publishing Torah? Should not the questioner ask, the Jewish People are drowning in a sea of tears and you are singing?…This, however, is the power of the Jewish People and their commitment to God and Torah that in every period—even as the sword is pressing against their neck—Torah remained a delight every day.

Rav Chaim Ozer passed away on the 5th of Av, Friday, August 9th, 1940. The spiritual father of the migrating yeshivas, to borrow Klibansky’s description, his children were devastated. Trucks were rented to bring neighboring yeshiva students back to Vilna in time for the funeral. American Jewry was devastated as well—Rav Chaim Ozer had been in touch constantly with American rabbis to coordinate the war efforts. Agudath Israel, the organization that Rav Chaim Ozer helped found, organized a memorial service. Led at the time by Rabbi Eliezer Silver, whose great-great-grandson Rafi is my class (!), Rabbi Solovetichik was invited to deliver a eulogy. He knew Rav Chaim Ozer from his time in Berlin where they would spend time talking in Torah learning together. Had Rav Chaim Ozer married Rav Eliyahu Feinstein’s daughter, they would have been family. Rabbi Soloveitchik’s remarks turned to our parsha, Tetzaveh, and its description of the unique vestments of the Kohen Gadol, namely the tzitz and the choshen. The tzitz, Rabbi Soloveitchik explained, is worn on the head of the Kohen Gadol, representing Torah scholarship; the Choshen, with the names of the twelve tribes carved onto it, covered the heart of the Kohen Gadol, representing compassion and connection to the entirety of the Jewish People. True leadership, Rabbi Soloveitchik explained, must encompass both—the head and the heart. And that was Rav Chaim Ozer—who possessed both the head and heart to lead the Jewish people during one of the darkest periods in all of Jewish history.

Interestingly, as far as I know, the eulogy was never fully translated into English. It was however summarized in English in a May 1992 article of the Jewish Observer, marking the 70th anniversary of Agudath Israel, the organization that Rav Chaim Ozer helped found.

And that brings us back to our original question on this week’s parsha.

Moshe pleads with God to forgive the Jewish People after the sin of the Golden Calf. Erase me from your book, Moshe cries! Moshe is not willing to continue his leadership without the Jewish People.

Like Rav Chaim Ozer, in times of pain and crisis, he refused to leave the side of his people.

So Hashem removes his explicit name from Parshas Tetzaveh. Instead, his name is alluded to implicitly—through gematria and other allusions. This is the ultimate form of leadership—the very subject of our parsha. The highest form of leadership is when the legacy and vision of the leader remain present even when it is not explicitly there. It is the unbreakable bond, as the Lubavitcher Rebbe once explained, between the Jewish people and their leader Moshe that even when he is not explicitly present, he can still be found.

And it is that leadership, embodied by Moshe and leaders of the generation like Rav Chaim Ozer, that continues to steward the hearts and minds of the Jewish people. Even in their explicit absence, we remain connected.

Special thank you to my friend Duvi Safier for sharing the incredible letters and telegrams cited above!

Shabbos Reads — Books/Articles Mentioned

Raban Shel Kol Bnei HaGoleh, Dovid Kaminetsky

The Golden Age of Lithuanian Yeshivas, Ben-Tsiyon Klibansky

Rakafot Aharon (Volume 1), Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff

When History is His Story A Review of R. Dovid Kamenetsky’s “Rabeinu Chaim Ozer: Raban Shel Kol B’nei Ha’golah, Jonah Steinmetz

Check out All Parsha, where you can find weekly audio of Reading Jewish History in the Parsha, as well as other incredible presenters and amazing features that will enhance your Parsha journey!

Reading Jewish History in the Parsha has been generously sponsored by my dearest friends Janet and Lior Hod and family with immense gratitude to Hashem.

You mentioned R' Rakeffet, and referenced one of his books, but you neglected to quote what R' Rakeffet always says regarding that eulogy: R' Soloveitchik changed his mind 180 degrees regarding the role of Gedolim in leadership and politics, and left the Aguda. R' Rakeffet points to the March on Washington urging the US Govt to intervene in protecting Jews in Europe, which did nothing. He writes about it in his biography of the Rav.