The accompanying shiur is available on the Orthodox Union's parsha learning app: All Parsha.

The third book of the Torah, Vayikra, ends with whispers. In our parsha, the long list of curses that will befall the Jewish people, known as the tochacha (lit. rebuke), is traditionally read in a whispered tone. Even whispered, the curses are frightening—destruction of Jewish civilization, exile among the nations, running in fear without even knowing who is pursuing us.

Why does Sefer Vayikra end on this note?

This is not the only list of curses we have in the Torah. A second tochacha appears in Sefer Devarim, Parshas Ki Savo. Ramban in our parsha explains that the list of curses in our parsha refers to the exile after the destruction of the first Beis Hamikdash, while the tochacha in Parshas Ki Savo refers to the pains of our current exile, following the destruction of the second Beis Hamikdash.

Interestingly, as the curses grow more and more harrowing, the Torah tells of a time when the sound of a driven leaf—later used for the title of Milton Steinberg’s classic novel on Elisha ben Avuya—will cause the Jewish people to flee and they will not even know who is pursuing them. As they run, without it even being clear if they are actually being persecuted, they will stumble over one another. The Talmud interprets this imagery to mean that Jews are responsible for one another (כל ישראל ערבים זה בזה) and will be punished for one another’s sins.

Why is our collective responsibility for one another introduced in such a negative context? Isn’t this supposed to be inspiring—why is it introduced as the reason for our exile?

And finally, our list of tochacha ends with some measure of comfort—God promises that he will still remember the covenant he made with our forefathers. There is no such comfort in the tochacha of Parshas Ki Savo. Why does our tochacha include such words of consolation as opposed to the list in Sefer Devarim? What is the function of these comforting words?

To understand all this, let’s explore the context of one famous American’s reflections on the Jewish People.

In 1867, Samuel Langhorne Clemens boarded the USS Quaker City, a former Civil War steamship, for an extended travel through Paris, Rome, and the Black Seas of Odessa. Its final destination would be the Holy Land. Clemens would eventually publish his experiences on this journey in his book, The Innocents Abroad, or The New Pilgrim's Progress, under his famed pen name Mark Twain. It would become his best selling book within his lifetime.

Twain’s portrait of the Holy Land is not flattering. He describes a diseased society, “they were infested with vermin, and the dirt caked on them till it amounted to bark.” The people who he confronted were not actually Jews, as Twain himself acknowledged, but throughout his book, associations he draws from the Holy Land are to an ancient world, untouched by modernity, and riddled with disease. As Sander L. Gilman, explains in his article “Mark Twain and the Diseases of the Jews,” Twain’s first published confrontation with the Jewish people is through a clearly Christian lens. As Gilman writes:

Thus the central question which Twain presents in his image of the Jews, reaching from the biblical leper Naaman to their contemporary surrogates, is their diseased nature and its relationship to their essence. It mirrors Twain's own questioning of his internalization of the Judeo- Christian presuppositions of the Bible. Disease and religion are indeed linked, but they are linked in the very essence of the Jew.

Twain’s impression of the Holy Land and the Jewish People would dramatically evolve over the course of his life. In 1897, Twain visited Vienna with his family in the hopes of earning some extra money on the lecture circuit. Instead, he confronted something else entirely: antisemitism. As my friend, Rabbi Elie Mischel writes in his fascinating exploration, “The Enigma of Mark Twain: Jews’ Best Friend or an Inadvertent Antisemite?:”

Expecting a pleasant and unremarkable stay in the imperial capital, the family had no inkling of the maelstrom of antisemitism that awaited them.

Rabbi Mischel explains the changing landscape of Vienna that Twain confronted:

Twain’s visit to Vienna coincided with a new wave of antisemitism in the Austro-Hungarian empire. A few months earlier, the infamous antisemite Karl Lueger was elected mayor of Vienna, lending official respectability to a form of blatant and public antisemitism that previously had simmered beneath the surface of respectable society. Hitler would later describe Lueger as “the greatest German mayor of all time” in his infamous autobiography Mein Kampf. In those days, Vienna was, in the words of journalist Carl Dolmetsch, a “cesspool of antisemitism.” Meanwhile, the infamous Dreyfus affair, in which a Jewish French army captain was falsely accused of spying for Germany, reverberated throughout Europe, triggering a wave of antisemitic riots in over twenty French cities in early 1898.

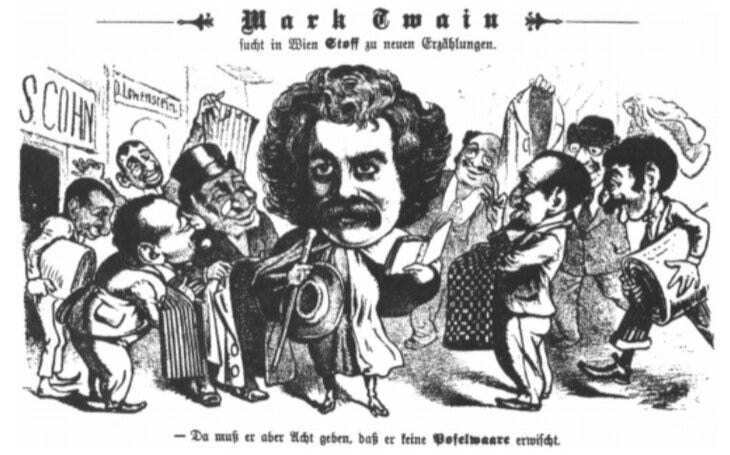

While in Vienna, Twain granted interviews to a few Jewish writers. He had grown fond of the Jewish people, especially the Yiddish stories of Shalom Aleichem. After Sholom Aleichem was described as the Jewish Mark Twain, he famously remarked, “I’m the American Sholem Aleichem.” Cozying up with Jewish writers, however, was not well-received by Vienna’s non-Jewish journalists. An antisemitic Viennesse newspaper ran a political cartoon mocking Twain’s relationship with the Jewish people. Some even accused him of secretly being a Jew himself!

Twain was unimpressed that a cultured society could be capable of such bigotry. He grew more and more sympathetic to the Jewish People. The writing of Theodore Herzl, who served as a journalist during the Dreyfus Affair, resonated with Twain’s first-hand experiences with antisemitism. Twain wrote approvingly, though humorously, of the vision of Zionism—"If that concentration of the cunningest brains in the world was going to be made in a free country (bar Scotland), I think it would be politic to stop it. It will not be well to let that race find out its strength. If the horses knew theirs, we should not ride any more"

While Twain made jokes about many other ethnicities, Twain’s daughter Clara later recalled that the prevalence of antisemitism prevented him from mocking Jews:

Papa at first did not know himself why it was that he had never spoken unkindly of the Jews in any of his books, but after thinking awhile he decided that the Jews had always seemed to him a race much to be respected; also they had suffered much, and had been greatly persecuted, so to ridicule or make fun of them seemed to be like attacking a man that was already down. And of course that fact took away whatever there was funny in the ridicule of the Jew.

In 1898, Twain wrote an article entitled, “Stirring Times in Austria,” where he mocks the recent rise in antisemitism. “They are religious men, they are earnest, sincere, devoted,” Twain wrote about the enlightened culture at the time, “and they hate the Jews.” An American lawyer wrote to Twain, following the publication of “Stirring Times in Austria,” inquiring about the roots of antisemitism and how it can be combatted:

Tell me, therefore, from your vantage-point of cold view, what in your mind is the cause. Can American Jews do anything to correct it either in America or abroad? Will it ever come to an end? Will a Jew be permitted to live honestly, decently, and peaceably like the rest of mankind? What has become of the Golden Rule?

In response to this query, Twain wrote his most famous and comprehensive treatment of the Jewish people, an essay entitled “Concerning the Jews,” first published in Harper’s Magazine in September of 1899. Over 7000 words, Twain explains the essay is meant to address 6 points:

1. The Jew is a well-behaved citizen.

2. Can ignorance and fanaticism alone account for his unjust treatment?

3. Can Jews do anything to improve the situation?

4. The Jews have no party; they are non-participants.

5. Will the persecution ever come to an end?

6. What has become of the Golden Rule?

The essay is cited most frequently for its concluding reflection on the eternity of the Jewish people. It is always worth rereading:

To conclude.—If the statistics are right, the Jews constitute but one per cent of the human race. It suggests a nebulous dim puff of star-dust lost in the blaze of the Milky Way. Properly the Jew ought hardly to be heard of; but he is heard of, has always been heard of. He is as prominent on the planet as any other people, and his commercial importance is extravagantly out of proportion to the smallness of his bulk. His contributions to the world’s list of great names in literature, science, art, music, finance, medicine, and abstruse learning are also away out of proportion to the weakness of his numbers.

He has made a marvellous fight in this world, in all the ages; and has done it with his hands tied behind him. He could be vain of himself, and be excused for it. The Egyptian, the Babylonian, and the Persian rose, filled the planet with sound and splendor, then faded to dream-stuff and passed away; the Greek and the Roman followed, and made a vast noise, and they are gone; other peoples have sprung up and held their torch high for a time, but it burned out, and they sit in twilight now, or have vanished.

The Jew saw them all, beat them all, and is now what he always was, exhibiting no decadence, no infirmities of age, no weakening of his parts, no slowing of his energies, no dulling of his alert and aggressive mind. All things are mortal but the Jew; all other forces pass, but he remains. What is the secret of his immortality?

Twain was quite proud of the essay even though he knew it would not be celebrated by either his Jewish or Christian readers. “The Jew article is my gem of the ocean,” Twain later wrote in a letter, “Neither Jew nor Christian will approve of it, but people who are neither Jews nor Christians will, for they are in a condition to know truth when they see it.”

Twain’s essay was incredibly influential and widely read in both Jewish and non-Jewish circles. Some have even argued that Twain’s essay was the unnamed inspiration behind Sigmund Freud’s 1938 work, “A Comment on Anti-Semitism.” Many Jews championed Twain’s essay as a powerful testament to Jewish survival. In 1992, the ADL (Anti-Defamation League) republished Twain’s essay along with an introduction from its then national director Abe Foxman. Foxman positively described the essay as “sounding a warning” for the dangers of antisemitism. Others felt Twain exacerbated those very same dangers with the publication of his essay. Andrea Greenbaum wrote an essay entitled, "A Number One Trouble Maker: Mark Twain’s Anti-Semitic Discourse in Concerning the Jews,” which characterizes Twain’s essay as “perhaps inadvertently, perpetuates the Jewish caricature - relentless in business, physically weak, and politically impotent.” Dan Vogel directly responded to Greenbaum’s concerns in a later essay, “Concerning Mark Twain’s Jews,” which defends Twain’s presentation of the Jewish people and accuses Greenbaum of misleading analysis of Twain’s work.

That is part of the paradox of any discussion of antisemitism—often the very traits Jews are demonized for are also the reason why they are admired. As Rabbi Mischel poignantly concludes his treatment of Twain’s relationship with the Jewish people:

But for all of his good intentions, Twain never grasped that the Jewish People’s unique aloneness is not only the root of its suffering, but also the secret to its miraculous survival and success. As painful as it may sometimes be, the Jewish People understand that aloneness is not a curse, but a blessing.

And this brings us back to the parsha and the uniqueness of the tochacha.

Sefer Vayikra seems to end on a haunting note. But the tochacha can also be read as a positive climax. The entire Sefer Vayikra is about God dwelling among the Jewish People through the building of the Mishkan and offering sacrifices. One could rightfully presume that if we no longer have such a house for God it must indicate that God has abandoned us. And that is exactly why Sefer Vayikra ends with the tochacha, the description of the destruction of the first Beis Hamikdash, our first national experience of exile. God is reminding us that no matter the hardships and suffering of exile, the Jewish People will never be completely abandoned by God. The entire Sefer Vayikra ends with the reminder that God’s ultimate and eternal dwelling place is within the Jewish People.

This is the reminder of the concluding comfort of the tochacha—God will never forget the Jewish People even when the Jewish People seem to forget God. And that is why specifically within these harrowing verses, the Talmud derives the principle of כל ישראל ערבים זה בזה, the collective responsibility of the Jewish People. Alone in the world, Jews must assume responsibility for one another. Our isolation and our connectedness are always intertwined with one another.

And this, more than any other explanation, may be the answer to Twain’s question, “What is the secret to his immortality?” The answer, of course, is the eternal promise that God made to the Jewish People. Even in our darkest moments, even when we seem to be rejected by the world, נצח ישראל לא ישקר, the eternity of the Jewish People is undeniable.

As Rabbi Sacks beautifully writes:

The people may be faithless to God but God will never be faithless to the people. He may punish them but He will not abandon them. He may judge them harshly but He will not forget their ancestors, who followed Him, nor will He break the covenant He made with them. God does not break His promises, even if we break ours.

Shabbos Reads — Books/Articles Mentioned

Mark Twain's Philosemitism: "Concerning the Jews," Sholom J. Kahn

Mark Twain and the Diseases of the Jews, Sander L. Gilmen

The Enigma of Mark Twain: Jews’ Best Friend of an Inadvertent Antisemite?, Elie Mischel

Philo-Semitism as Anti-Semitism in Mark Twain's "Concerning the Jews," Bennet Kravitz

The Lost Source in Freud’s “Comment on Anti-Semitism”: Mark Twain, Marion B. Richmond

A Number One Trouble Maker: Mark Twain’s Anti-Semitic Discourse in Concerning the Jews, Andrea Greenbaum

Concerning Mark Twain’s Jews, Dan Vogel

Check out All Parsha, where you can find weekly audio of Reading Jewish History in the Parsha, as well as other incredible presenters and amazing features that will enhance your Parsha journey!

Reading Jewish History in the Parsha has been generously sponsored by my dearest friends Janet and Lior Hod and family with immense gratitude to Hashem.

Another fantastic piece. I've heard and read excerpts from Twain's piece for years, but never heard the full story. Fascinating!

Also, as fate would have it, I just discovered on a whim "As a Driven Leaf" and purchased it two weeks ago.