The accompanying shiur is available on the Orthodox Union's parsha learning app: All Parsha.

There are more famous opening sentences than closing sentences.

“Call me Ishmael.”

“As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.”

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.”

Even those who are not so biblio-curious could likely identify which books these are from—spoiler alert—Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, and Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities.

But what about last lines? How many final sentences can you remember?

Interestingly, the Torah itself has one of the most famous last lines:

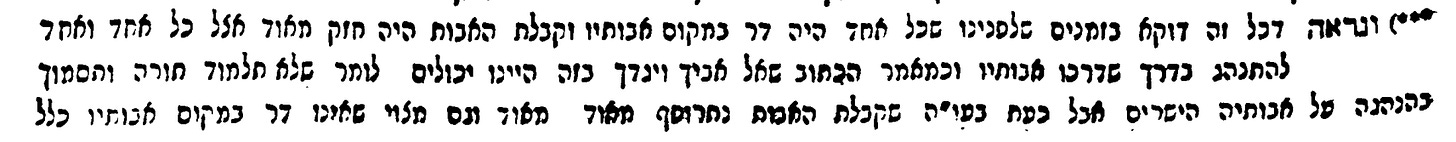

וּלְכֹל הַיָּד הַחֲזָקָה וּלְכֹל הַמּוֹרָא הַגָּדוֹל אֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה מֹשֶׁה לְעֵינֵי כׇּל־יִשְׂרָאֵל׃

And for all the great might and awesome power that Moses displayed before all Israel.

But that is not the only last line of the Torah.

Sefer Devarim is, in a sense, the beginning of a new Torah. Or at least the Torah from a new perspective. As opposed to the other books of the Torah, the entire Sefer Devarim is written in first-person through the eyes of Moshe. The nature of the sefer is clearly different than those before it.

In fact, in his introduction to Devarim the Abarbenel asks whether we should consider Sefer Devarim equally with the other books of the Torah. Is Sefer Devarim the word of God said from Moshe’s perspective or is this book really Moshe’s perspective that was later canonized within the Torah?

At the heart of Sefer Devarim is the question: What exactly is the nature of Sefer Devarim?

The unique status of Sefer Devarim raises another question about last sentences. In a sense, the Torah as the unmediated word of God really ends with Sefer Bamidbar. After Sefer Bamidbar, the Torah is given over through the eyes of Moshe. So how does the final book of the unmediated Torah of Hashem end before introducing Sefer Devarim? In short, pretty anti-climatically.

Sefer Bamidbar ends by returning to the story of the daughters of Tzelofchad, who were concerned that they would not inherit their father after his passing. In the final act of Hashem’s Torah before the reins are, so to speak, handed over to Moshe, we revisit an inheritance dispute. Why is this the last story we read in the Torah before stepping into the Torah through Moshe’s eyes in Sefer Devarim?

To understand this, let’s explore the life and legacy of Sarah Schenirer and the Beis Yaakov movement.

For most of Jewish history, Jewish education was reserved primarily for men, and a serious Jewish education was reserved primarily for men of great intellectual promise. Yeshivas were populated by those who could potentially become Jewish leaders. Jewish education was not seen as a basic necessity for Jewish children in the modern world. For most, especially women, Jewish education was transmitted in the home rather than in a yeshiva or a formal school.

Beginning at the turn of the 20th century, the lack of a formal Jewish schooling system began to take its toll, primarily on young women. Once secular public school systems began to flourish, women were given a strong basis of secular education but their Jewish education remained extraordinarily weak. Slowly, there began to be an epidemic of sorts with reports of young women leaving the traditional Jewish community—some converted or intermarried, some even became prostitutes. In 1900 there was an outcry within the Orthodox world when reports surfaced of a young Chassidic woman who planned on converting to marry her non-Jewish boyfriend.

Bertha Pappenheim, who would later be immortalized as Anna O. one of the earliest documented cases of effective psychotherapy, spoke out specifically about the concerns of prostitution within the Orthodox community. “There are an immense number of young Jewish women,” Bertha writes, “who fall into prostitution even while they are still living with their very religious parents.” In 1912, she met with the Aleksanderer Rebbe in the hopes of marshaling his leadership on this matter. Not much came from the meeting, though the rebbe was quite concerned.

Something needed to be done. The old model was clearly not working.

And it is here that the story of Sarah Schenirer is told in multiple ways. According to the traditional accounting, preserved in the memories of most Beis Yaakov students until today, Ms. Schenirer, after securing the approbations and agreement of leading Torah leaders decided to begin a women’s education revolution by opening schools known as Beis Yaakov.

That, of course, is not the entire story.

As Leslie Ginsparg Klein demonstrates in her incisive article, “Sarah Schenirer and Innovative Change: The Myths and Facts,” there has been a considerable amount of revisionist history in the retelling of Sarah Schenirer’s founding of Beis Yaakov. Most importantly, the role of rabbinic approval—most notably that of the Chofetz Chaim—is often exaggerated in modern retellings to frame her revolution as working with the direct approval of rabbinic leadership. In truth, while her brother, a Belzer chossid, did consult with his rebbe, the Belzer rebbe, alongside his sister Sarah Schenirer (the rebbe wished them bracha v’hatzlacha, much success), Sarah Schenierer did not actively solicit direct rabbinic approval for her movement. As Sarah Schenirer writes in her memoir:

I could not get my dream of establishing a religious school for girls out of my head. At first [my brother] laughed at me. “Why do you want to start busying yourself with political parties?” he wrote back. But when I answered him that I was firmly resolved not to abandon this mission, he wrote me: “Nu, let us go to Marienbad where the Belzer Rav is now, and we will hear whether the tzaddik of the generation agrees to it.” There was no end to my joy. Although I did not have much money, I hurriedly prepared myself for the trip. When I arrived in Marienbad, I and my brother went immediately to the Belzer Rav. My brother, who was a ben bayis there, wrote in his kvittel: “She wants to educate Jewish daughters in the Jewish derech,” and I heard the answer from the tzaddik’s holy mouth myself: Bracha v’hatzlacha. The words were like the most expensive balsam oil, instilling fresh courage in my limbs. The blessing from the great tzaddik gave me the best hope that my strivings would be fulfilled.

And while the Chofetz Chaim did address the issue of women’s education in his halakhic work Likkutei Halachot, the work was published in 1911—before Sarah Schenirer opened up her first school.

It was only in 1933 that the Chofetz Chaim wrote a letter directly giving his approval for the Beis Yaakov movement. But that letter was not written at Sarah Schenirer’s behest—it was Agudath Israel who had requested the letter to convince a local rabbi to allow a Beis Yaakov to open up in his community. It was not rabbinic approval that allowed the Beis Yaakov movement to flourish; rather, the movement's success garnered the approval. As Dr. Ginsparg-Klein writes:

What changed and ultimately garnered Bais Yaakov rabbinic and communal approval was the movement’s success. Sarah Schenirer’s first school grew from 25 students to 40 within a few months and other towns began petitioning Schenirer for help replicating her school in their locations. Her accomplishments caught the attention of the local Agudath Israel branch in 1919, which lent support to the fledgling school. In 1924, the national Agudath Israel adopted the Bais Yaakov school system, accepting fiduciary responsibility. Founded by adherents of Rabbi Hirsch, Agudath Israel sought to improve education in Eastern Europe, including how girls were educated. Additionally, Agudath Israel was a political party within the Polish parliament and wished to court the vote of women, who had been awarded the right to vote in 1918.

Sarah Schenirer dreamed of a world where women could fully actualize themselves. In many ways, she was disinterested in the traditional life expected of most women at the time. Her 1910 marriage ended in 1913—though it was already clearly falling apart just a year into the union. She wanted a more loving marriage and a husband who was more attentive to her spiritual ambitions. In some ways, the marriage was doomed from the start. In a 1910 diary entry entitled, “The last day before my wedding,” Schenirer confided her desire for a different kind of life:

When I think about that, I just can’t stop crying. But maybe I should be brave enough to say: ‘No! I don’t want to!’ Only you, my dear diary, allow me to express it all, even as you keep silent, stubbornly silent. And my ideal, somewhere in my soul, is only to work for my sisters! Oh, if I could only persuade them one day what it means to be a true Jewish woman, who doesn’t do things just because of her mother or because she’s afraid of her father, but only out of true love for the Creator himself, who has elevated us above all the nations and sanctified us with his commandments. Ah! If I could manage to do that, I would be so happy, a hundred time happier than any millionaire. Have I lost my mind? Now, in this era of progress, I dream about something like that.

Throughout this period in Sarah Schenirer’s life, she was preoccupied with the dream of working alongside Jewish women to create a world of new spiritual opportunities in the modern world.

One of the most definitive perspectives on Sarah Schenirer’s motivations and the early years of Beis Yaakov comes from a different diary, that of Bracha Levin. Schenirer also kept a diary though it has not been published in its entirety. Still, Naomi Seidman, in her incredible work, Sarah Schenirer and the Beis Yaakov Movement: A Revolution in the Name of Tradition, translates large portions of it. More recently, the diary of Bracha Levin, a Lithuanian Orthodox woman, was published in 2013, originally in Hebrew, and later translated and analyzed by Rachel Manekin in her eye-opening article, “The Cracow Bais Yaakov Teachers’ Seminary and Sarah Schenirer: A View from a Seminarian’s Diary.” Levin’s diary provides a window not only into the motivations of Sarah Schenirer in establishing the Beis Yaakov movement but also on the experiences of a young student in their Teacher’s college in those early years.

In one passage in Levin’s diary, she recalls a time when Schenirer shared how the original idea of starting Beis Yaakov came about. It began, according to Levin’s retelling, when Sarah Schenirer heard a sermon from Rabbi Moshe Flesch on Shabbos Chanukah about the heroics of Judith. She was so moved by the rabbi’s words that she wanted to find the original Torah sources that the rabbi was drawing upon. She bought the commentary of Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch on Psalms as well as the commentary of Marcus Lehmann on Pirkei Avos, and began sharing Torah thought with young women. Her Chassidic brother teased her that she was beginning to look like a Zionist, who at the time were also very involved in Jewish education. At her brother’s behest they went to visit the Belzer Rebbe, who wished her success but, according to Levin’s retelling, urged her not to teach Hebrew. That was not a problem, despite her best efforts Schenirer was never able to learn the Hebrew language.

Schenirer realized that the key to Jewish influence was becoming more fluent in Torah. As she writes:

I myself, however, did not know anything! I took a prayer book with a translation, and every day I first taught myself to translate the words of the prayers and the blessings into Yiddish and this is what I later taught to my pupils. It was very hard work. The language was foreign to me but the ideal gave me strength to suffer, struggle, and win. And indeed I succeeded. I received help from heaven. My idea spread more and more and found for itself a broader horizon. Later, there were people who helped me in my work, and so my ideal developed until it was realized in the Bais Yaakov seminary.

Aside from the stories about the formation of Beis Yaakov, Bracha Levin’s diary offers a fascinating glance into the world of the early Beis Yaakov schools. When Levin first arrived at the seminary in 1929, she felt considerably out of place. As opposed to the Chassidic women who predominantly came from Poland, Bracha was Lithuanian and had more modern sensibilities than her Chassidic counterparts. Much like Beis Yaakov schools today, there were questions about authenticity and modesty that bothered Bracha when she first arrived. She writes:

I have delved deeply into the life in our institution. Not just me, but also the very devout, the Hasidic daughters, have noticed it. In another half a year, the second year will produce its teachers. Is there one among them whose external behavior reflects her inner conviction? They are all full of flattery and deception. They pretend to be devout in front of the teachers but when walking out to the park they allow themselves everything. They wear dark stockings in front of Mrs. Schenirer, but for the park the stockings are completely light. On account of this, a big fight erupted between our Lodz students and the students of the second year. Sala, who is considered the most beautiful among them, told us about her being photographed wearing a bathing suit. And she will be a “Bais Yaakov” teacher? Not even one of the Tarbut seminary students would consider being photographed half-naked.

It’s not hard to imagine a modern community Beis Yaakov dealing with similar issues—trying to appeal to women from different types of homes and communities, while not alienating them. There’s a comfort in knowing that the struggle of Beis Yaakov rebels changing into less modest clothes while not in school was a phenomenon that was present at Beis Yaakov’s inception.

The social politics between the women at the time also has some modern-day resonance. Bracha complains about the cultural and religious differences between the girls from Poland and Lithuania:

I do not know why, but what an abyss there is between the girls from Poland and the girls from Lithuania, what a mutual lack of understanding! I started talking to them [the Lithuanians] about the way they conduct themselves at home. Much to my great surprise, I saw that almost all the Lithuanians continued to behave as they did before attending Bais Yaakov. The little impression it had made on their behavior when they were in school completely disappeared. All of them continued to visit the movies and the theater. Chaya rode the bicycle and took walks with guys, and so on. It is a somewhat sad sight. We see from this that the influence of Bais Yaakov is limited if it can have an impact only within its own environment. Indeed, whence would be the source of its influence on us? We the Lithuanians with the tormented hearts, we need recognition. Unlike some of the Hasidic daughters, we can’t say: “What do you mean? Mrs. Schenirer said it is forbidden, and that is why it is forbidden!” After all, there are many other Orthodox sources from which one may draw a conclusion. I have read and heard about many exalted religious figures. Why won’t they let us read books that provide us with some sort of basis that would allow me to know what I ought to love and what I should hate. . . . When my soul is fed up with the dry studies, and I yearn a little for more nourishment, I approach my Hebrew books that I brought with me. For example, Gordon’s poetry [Judah Leib Gordon, 1830–1892, one of the most important poets of the Haskalah]. Or instead, I could have read something that opposes him, something that would have filled up the void inside me, and some of the Lithuanians.

Bracha did not want a Jewish education that amounted to just information, she wanted a Jewish education that made her feel seen. “We are in need not only of a teacher, but of a friend,” Bracha writes, “a friend who would live among us, not high above us, and who would take part in our joys and feel us when we are distressed.”

Like many modern-day young men and women, Bracha was frustrated at times when she didn’t understand the reasons behind Jewish practice. As she writes:

We study here religious laws [dinim] that even my devout father was never strict about, but here they are considered a severe violation. Sometimes, when I ask for the reason of a prohibition, she [Schenirer] tells me, “Because this is how it should be. I myself do not know why.” A nice response for my skeptical soul! Do I need to follow all these things that even Mrs. Schenirer, who is called our “spiritual mother,” doesn’t know why she follows, and that my heart tells me are time-bound things [from which women are exempt] of little value?

Despite her frustrations, Bracha Levin warmed up considerably to Sarah Schenirer and began to see her not only as a role model but as an ideal woman. After a few disgruntled months, she began to deeply respect Sarah Schenirer:

The truth is that our principal, Sarah Schenirer, is an ideal woman, good as an angel. She would never say a bad word about any person and works hard each day without taking anything for herself. She cares for us like a mother, and her devoutness, though a bit exaggerated, comes from the depth of her soul and faith. She is pure. Doesn’t one need to respect a woman like that? Are we to bow down in front of those women who adorn themselves and spend most of their money for vanity to fulfill all their foolish desires? Here we see a great aspiration to labor for the soul of the people.

Still, even as her admiration for Schenirer grew, Bracha at times remained quietly skeptical if Sarah Schenirer’s model of religious devotion was accessible to young women like herself:

I love her very much, but what can she give me? Her devoutness is the one of an innocent child. She is very simple and does not know life at all. Her devoutness stems from her heart, not from her mind, and that is why there is nothing she could give to me. We all love her and are ready to do everything for her.

Sarah Schenirer passed away in 1935. Shortly before her death, she sent a letter to be read at the last siyum of the Beis Yaakov seminary. She urged the young women to stay pure and focused on their holy work—never being too self-congratulatory or too dismissive about their own potential. To the young teachers graduating from Beis Yaakov’s teacher’s seminary, she writes:

You, dear children, are going out into the wider world and will be entrusted with the pure souls of children. You have to raise these souls as true people of Israel!

Remember, the fate of the younger generation, and thus of the entire people is dependent on you…

The holy Torah ends with the words, “and for all the great might and awesome power that Moses displayed before all Israel” [Duet. 34:10]. This teaches us that the righteous man has the same power as God to perform miracles…

And this brings us back to our parsha and the nature of Sefer Devarim.

Sefer Devarim is deliberately expressed through the perspective of Moshe as a reminder that our own perspective is a part of the unfolding of the Torah. In other words, Sefer Devarim is the beginning, so to speak, of the Torah sh’baal Peh, the Oral Torah. It is the perspective of orality canonized within the written book—leading to the ultimate culmination which is the final words of the the Sefer that reinforce, as Sarah Schnerir explained, the power and potential of humanity to express divinity. The first four books of the Torah are written from God’s perspective, explains the Maharal, and the final book of the Torah is written from a human perspective.

And this is why Sefer Bamidbar ends by returning to the story of the daughters of Tzelofchad.

The Rebbe of Izhbitz, Rav Mordechai Yosef Leiner, explains that the reason we return to the story of the daughters of Tzelofchad right before beginning Sefer Devarim is to remind the Jewish People that in the world of Sefer Devarim, where Torah begins to be mediated through a human perspective, we will need the added initiative to apprehend divinity in this world. The daughters of Tzelofchad were not content without realizing their share of the inheritance of the land of Israel. They wanted a Torah that addressed their perspective and their state within the world—they demanded a share in the Torah.

And this in many ways is exactly the revolution of Sarah Schenirer. Oftentimes her legacy is mischaracterized as a revolution in women’s Jewish education. It was that, but it was not only that. Her primary revolution was in the nature of education itself—for men and women—realizing that in this modern world, every Jew needed the basic foundation of Jewish education. No longer for elites or rabbis, Jewish education became essential for the formation of Jewish identity—the core idea of education that still endures today. And it all began with a woman who insisted that she too had a share in our richest inheritance, תורה צוה לנו משה מורשה קהלות יעקב, the Torah itself.

Shabbos Reads — Books/Articles Mentioned

Sarah Schenirer and the Beis Yaakov Movement: A Revolution in the Name of Tradition, Naomi Seidman

Ongoing Constitution of Identity and Educational Mission of Bais Yaakov Schools: The Structuration of an Organizational Field as the Unfolding of Discursive Logics, Shoshanah M. Bechhofer

Sarah Schenirer and Innovative Change: The Myths and Facts, Leslie Ginsparg Klein

Legitimizing the Revolution: Sarah Schenirer and Orthodox Girls Education, Naomi Seidman

The Cracow Bais Yaakov Teachers’ Seminary and Sarah Schenirer: A View from a Seminarian’s Diary, Rachel Manekin

Check out All Parsha, where you can find weekly audio of Reading Jewish History in the Parsha, as well as other incredible presenters and amazing features that will enhance your Parsha journey!

Reading Jewish History in the Parsha has been generously sponsored by my dearest friends Janet and Lior Hod and family with immense gratitude to Hashem.