On the Loss of a Leader

On V'Zos HaBracha and the controversy over the legacy of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik

The accompanying shiur is available on the Orthodox Union's parsha learning app: All Parsha.

I don’t remember when I first learned that the Torah ends with Moshe's death. I wish I did. It’s such a haunting ending that we too often take for granted because we have become so familiar with it.

In Franz Kafka’s Diaries, his entry for October 19, 1921, reflects on the ending of the Torah:

He has scented Canaan all his life; that he should see the land only before his death is unbelievable. This final prospect can only have the purpose of representing how incomplete a moment human life is, incomplete because this sort of life could last forever and yet the result would again be nothing but a moment. It is not because his life was too short that Moses does not reach Canaan, but because it was a human life.

As I once wrote in an article entitled, Unfinished Endings, there is a lot of wisdom in Kafka’s reading:

In Kafka’s reading, the Torah’s ending reflects the larger reality of human life itself, which is “nothing but a moment,” an exercise in incompleteness. Our personal narratives don’t fit neatly into a box. They don’t have ribbons on top and rarely end with group hugs. Human life ends unrequited, ever yearning, ever hoping. As Aviva Gottlieb Zornberg writes in her magisterial biography of Moses: “Veiled and unveiled, he remains lodged in the Jewish imagination, where, in his uncompleted humanity, he comes to represent the yet-unattained but attainable messianic future.”

The uniqueness of the ending of the Torah is not just about how it ends but how it was transmitted. Those final 8 verses which tell of the death of Moshe are subject to a dispute in the Talmud as to how they were written:

אָמַר מָר: יְהוֹשֻׁעַ כָּתַב סִפְרוֹ וּשְׁמוֹנָה פְּסוּקִים שֶׁבַּתּוֹרָה. תַּנְיָא כְּמַאן דְּאָמַר: שְׁמוֹנָה פְּסוּקִים שֶׁבַּתּוֹרָה יְהוֹשֻׁעַ כְּתָבָן. דְּתַנְיָא ״וַיָּמׇת שָׁם מֹשֶׁה עֶבֶד ה׳״ – אֶפְשָׁר מֹשֶׁה מֵת, וְכָתַב: ״וַיָּמׇת שָׁם מֹשֶׁה״?! אֶלָּא עַד כָּאן כָּתַב מֹשֶׁה, מִכָּאן וְאֵילָךְ כָּתַב יְהוֹשֻׁעַ; דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי יְהוּדָה, וְאָמְרִי לַהּ רַבִּי נְחֶמְיָה.

The Master said above that Joshua wrote his own book and eight verses of the Torah. The Gemara comments: This baraita is taught in accordance with the one who says that it was Joshua who wrote the last eight verses in the Torah. This point is subject to a tannaitic dispute, as it is taught in another baraita: “And Moses the servant of the Lord died there” (Deuteronomy 34:5); is it possible that after Moses died, he himself wrote “And Moses died there”? Rather, Moses wrote the entire Torah until this point, and Joshua wrote from this point forward; this is the statement of Rabbi Yehuda. And some say that Rabbi Neḥemya stated this opinion.

אָמַר לוֹ רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן: אֶפְשָׁר סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה חָסֵר אוֹת אַחַת, וּכְתִיב: ״לָקֹחַ אֵת סֵפֶר הַתּוֹרָה הַזֶּה״?! אֶלָּא עַד כָּאן הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא אוֹמֵר – וּמֹשֶׁה אוֹמֵר וְכוֹתֵב; מִכָּאן וְאֵילָךְ הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא אוֹמֵר – וּמֹשֶׁה כּוֹתֵב בְּדֶמַע, כְּמוֹ שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר לְהַלָּן: ״וַיֹּאמֶר לָהֶם בָּרוּךְ: מִפִּיו יִקְרָא אֵלַי אֵת כׇּל הַדְּבָרִים הָאֵלֶּה, וַאֲנִי כּוֹתֵב עַל הַסֵּפֶר בַּדְּיוֹ״.

Rabbi Shimon said to him: Is it possible that the Torah scroll was missing a single letter? But it is written: “Take this Torah scroll” (Deuteronomy 31:26), indicating that the Torah was complete as is and that nothing further would be added to it. Rather, until this point the Holy One, Blessed be He, dictated and Moses repeated after Him and wrote the text. From this point forward, with respect to Moses’ death, the Holy One, Blessed be He, dictated and Moses wrote with tears. The fact that the Torah was written by way of dictation can be seen later, as it is stated concerning the writing of the Prophets: “And Baruch said to them: He dictated all these words to me, and I wrote them with ink in the scroll” (Jeremiah 36:18).

Not only does the Torah end in such a sad way but there are actual Talmudic opinions that state Moshe did not even write the final eight verses! How could it be that our teacher Moshe was not given the privilege, at the very least, of completing his own book?!

Whichever opinion is accepted, the final eight verses of the Torah are endowed with a special halachic status, as explored in detail by Rabbi Daniel Z. Feldman in his article, “The Last Eight Pesukim in the Torah.” As opposed to the normal conventions of kriyas haTorah, the public Torah reading, the Talmud says that יָחִיד קוֹרֵא אוֹתָן—plainly, meaning an individual can read them. The exact meaning of this halacha is a widespread dispute among the commentators, carefully discussed and presented by Rabbi Feldman.

Still, we are left with the gnawing question of why the Torah ends so unconventionally. Would it not have been a greater honor for Moshe to be able to finish the Torah without any halachic questions or special status hovering over the ending?

To understand this, let’s explore some of the controversies that emerged in the wake of the passing of Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik.

Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik died at the age of 90, on April 9, 1993, corresponding to Chol Hamoed Pesach, 18 Nisan 5753.

Jamin Kaslowe reported on his funeral for Yeshiva University’s newspaper The Commentator. He wrote as follows:

Approximately 5,000 mourners filled the main sanctuary, the gymnasium, and the classrooms at the Maimonides School in Boston on Sunday, April 11 in what officials said was the largest Orthodox Jewish funeral ever held in New England. For two hours, Tehillim were recited over loudspeakers at the school in memory of the Rav, Rabbi Joseph Dov Soloveitchik. The mourners then listened as the Rav’s brother, YU Rosh Yeshiva Rabbi Aaron Soloveitchik, eulogized the Rav. Rav Aaron called his brother “the founder of the spiritual life of Jewish people. He had to penetrate information into students who were raised in an environment hostile to the Torah.” The coffin was then carried down the street for a short distance, as thousands followed.

The Rav was buried in the Beth El Cemetery in West Roxbury next to his wife, Tonya, who died in 1967. Funeral organizers said that thousands more would have attended the funeral, but the last days of Pesach were beginning Sunday night, and many people from outside the Boston area were worried that they would not be able to return home in time.

During his lifetime, Rabbi Soloveitchik was known, among many things, for his hespedim (eulogies)—and after his passing, there was no shortage of students and family members who commemorated his life and legacy. Many of these tributes were later collected into the volume Memories of a Giant edited by Michael A. Bierman. His passing was also noted in the New York Times with a long obituary by Ari L. Goldman.

Reflecting on the passing of his grandfather, Rabbi Mayer Twersky cautioned that Rabbi Soloveitchik should not be remembered in a small-minded way. “In our attempt to understand, depict and appreciate a few dimensions of the Rav’s multidimensional greatness,” Rav Twersky writes, “we dare not lower the Rav zt”l to our lowly spiritual station.” Clearly remarking on some of the inelegant tributes that had already been made, Rav Twersky reminded that “our personal insecurities or ideological inconsistencies must not distract us or cloud our vision of his multi-faceted harmonious genius and greatness.”

It is unclear who, if anyone, Rabbi Twersky was referring to but for many of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s students, there was one obituary that seemed to speaking from a clouded vision.

Just a few weeks after Rabbi Soloveitchik’s passing the May 1993 issue of The Jewish Observer, the monthly magazine of Agudath Israel, noted his passing with a description that many felt fell far too short of capturing Rabbi Soloveitchik’s greatness.

Under Rabbi Soloveitchik’s name were the words זכרונו לברכה, may his memory be a blessing, rather than the more common rabbinic superlative used זכר צדיק לברכה, may the memory of the righteous be a blessing. Other subtle digs can be detected as well, including highlighting his “admitted departure from the Torah world from which he came,” as well as the cumbersome closing sentence: “His passing leaves a vacuum in the specific role that he in effect created—a vacuum that cannot conceivably be filled by any other individual.” Hardly the description of a true vacuum left after the passing of a rabbinic leader.

In Zev Eleff’s article, ‘The Jewish Observer: Champion of the Orthodox Right,” on the legacy of The Jewish Observer, he notes how their obituary for Rabbi Soloveitchik was part of a larger effort to center Agudath Israel’s ideology and marginalize those considered more Modern Orthodox:

Rabbi Wolpin’s editorials preached allegiance to the Agudah’s rabbinic establishment, often at the expense of the “Moderns” and “Centrists” who sided with the Orthodox Union, Rabbinical Council of America and Yeshiva University and their champion, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, whose obituary was rather muted and made mention of how the Rav was “alone in the path he took.”

Many senior students of Rabbi Soloveitchik were quite hurt by what they saw as an undignified obituary for a Torah giant.

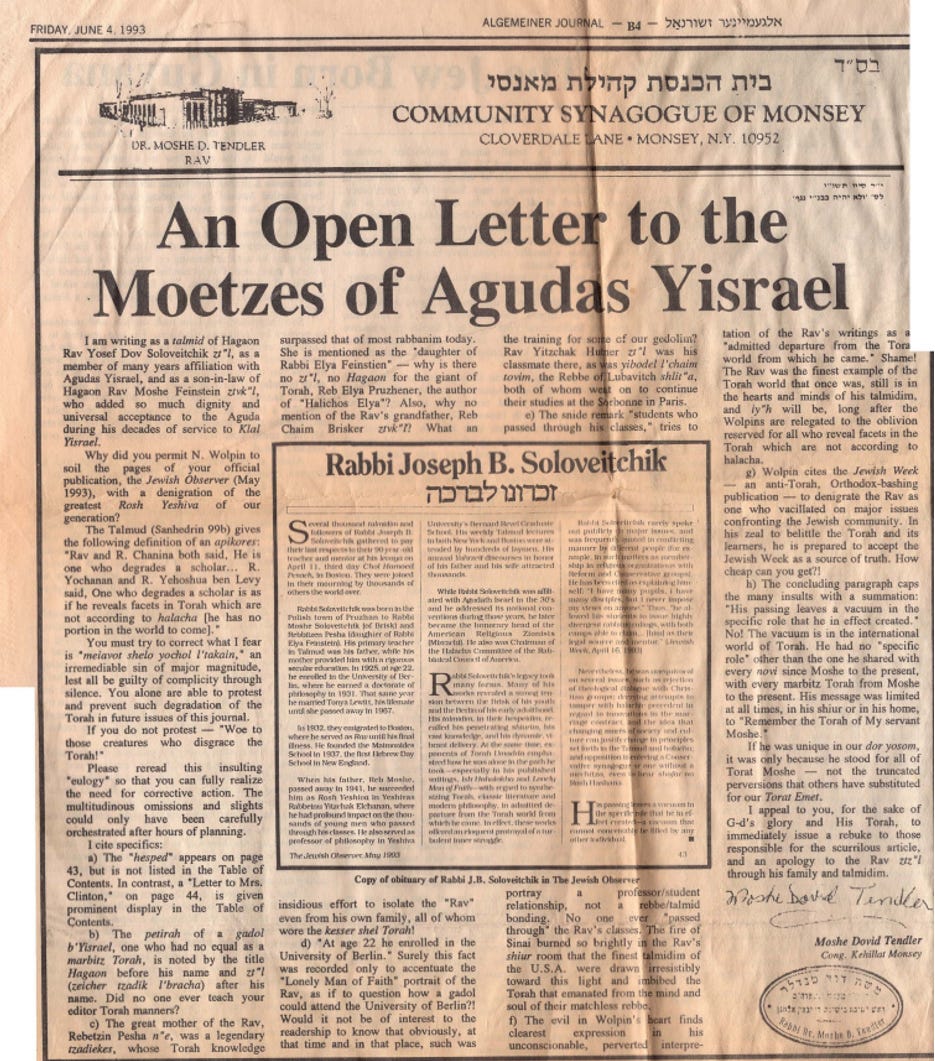

In the June 4th, 1993 edition of the Algemeiner Journal, Rabbi Dr. Moshe Tendler, a student of Rav Soloveitchik and son-in-law of Rav Moshe Feinstein published a full-page letter entitled, “An Open Letter to the Moetzes of Agudas Yisrael.” His distaste for the Jewish Observer’s decision to publish the previously mentioned obituary is not subtle. He directly asks the Moetzes, the rabbinic body of Agudath Israel, “Why did you permit N. Wolpin to soil the pages of your official publication, the Jewish Observer (May 1993), with a denigration of the greatest Rosh Yeshiva of our generation?,” he asks, referring to Rabbi Nissan Wolpin, longtime editor of the Jewish Observer. Rabbi Tendler then proceeded to list 8 offenses included within the obituary, which he deemed insulting and urged for corrective action to be taken immediately.

Given the context, a nearly Talmudic reading of an obituary measuring different slights in kavod, it is somewhat curious that Rabbi Tendler chose to use different superlatives in his letter for Rabbi Soloveitchik (zt”l) and his father-in-law, Rav Moshe Feinstein (ztvk”l, which stands for zecher tzadik v’kadosh l’vracha, may the memory of the holy righteous be remembered for a blessing). Honorific slights aside, Rabbi Tendler concludes with an appeal “for the sake of G-d’s glory and His Torah, to immediately issue a rebuke to those responsible for the scurrilous article, and an apology to the Rav zt”l through his family and talmidim.”

Rabbi Tendler was not alone in protesting the Jewish Observer’s obituary for Rabbi Soloveitchik. Rabbi Menachem Genack, also a student of Rabbi Soloveitchik as well as the CEO of the Orthodox Union, published an article entitled “Lo Chein Avdi Moshe”: The Rare Quality of Hagaon Rav Yosef Ber Soloveitchik, zt”l,” in the Jewish Press that also took issue with the obituary, which Rabbi Genack called “outrageously deficient.” While Rabbi Genack makes it clear that Rabbi Soloveitchik needs no defense, he ensures that the record is corrected “for the standard of excellence that the Rav personified.”

Not everyone agreed with Rabbi Genack’s estimation of Rabbi Soloveitchik. One emerging kollel student wrote to Rabbi Genack in the hopes of appealing to Rabbi Genack’s standing and understanding of the yeshiva world in order to explain why the yeshiva world, at the time, took such issue with Rabbi Soloveitchik. The six-page letter to Rabbi Genack lists grievances that the yeshiva world has with the legacy of Rabbi Soloveitchik. The letter, while addressed personally to Rabbi Genack, also made the rounds within the Jewish world.

Rabbi Genack responded to the concerns of the writer in the Friday, October 1, 1993 edition of the Jewish Press. After going through the writer’s points one by one, Rabbi Genack closes with a question:

We all have an important role in the survival of Yahadus in America and, beyond our triumphalism and self-congratulatory delusions, we are sadly falling short of any reasonable goals. No one more than the Rav took joy in the full Batei Midrash of the yeshiva world, including Yeshivat Rabbeinu Yitzchak Elchanan. But where dos this “us/them” mentality stop and Ahavas Yisrael begin?

Battles over the legacy of Rabbi Soloveitchik would continue for years after his passing. As is often the case, individuals who identified too right or too left of Rabbi Soloveitchik struggled to appreciate the scope of his legacy and appropriately estimate the greatness of his character.

In February of 1999, Edah, a progressive Modern Orthodox organization, held its first conference, ''Orthodoxy Encounters a Changing World,” at the Grand Hyatt Hotel in New York City. Although Rabbi Soloveitchik had passed several years prior, his legacy still loomed large at the conference. As the New York Times reported:

When nearly 1,500 modern Orthodox Jews gathered several months ago for their inaugural conference, the figure who dominated the proceedings was nowhere to be found among the rosters of speakers or panelists or people there. Rabbi Joseph Dov Soloveitchik had died six years earlier and had ceased most public activity nearly a decade before that.

Yet the convention of the group, Edah, featured no less than three sessions devoted to the life and work of the Rav — the teacher, as Rabbi Soloveitchik was reverently known. Four of his books were being sold. Even in a conclave thick with prominent rabbis and religious scholars, it was Rabbi Soloveitchik whom one saluted as the gadol, or great rabbi.

The conference, which discussed many emerging issues within the Modern Orthodox community, such as women’s prayer groups, was seen by many as a departure from the actual wishes of Rabbi Soloveitchik. Most notably, Rabbi Soloveitchik’s son-in-law, Rabbi Ahron Lichtenstein publicly responded to the use of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s legacy to buttress the ideology of the two-year-old Edah movement. In a March 1999 article published in The Forward entitled, “Take Rav Soloveitchik at Full Depth,” Rabbi Lichtenstein implored his readers not to “pigeonhole the Rav within the confines of a narrow ‘camp.’” Rabbi Lichtenstein's words, which included a scouring critique of Modern Orthodoxy are always worth revisiting (in fact, allow me to mention as an aside that my mother had this article hanging on the wall of her office for many years after it was published):

Shallowness is, however—and I say this as a devoted friend rather than as an adversary—the Achilles’ heel of much of Modern Orthodoxy. As such, it elicited some of the Rav’s sharpest critiques of religious modernism. Flaccid prayer, lukewarm commitment to learning, approximate observance, tepid experience — anything that reflected comfortable mediocrity in the quality of acculturated American Judaism, he deplored and sought to ennoble. This is not to suggest that he regarded the anti-modernists as his ideal. He had high standards of spirituality, and few met them fully. But with respect to this particular failing, I believe it is fair to state that both intellectually and emotionally, he regarded it as afflicting the modern community more than others. His ideological commitment to the cardinal concerns of Modern Orthodoxy—an integrated view of life, the value of general culture, and the significance of the State of Israel—and his genuine pride in some of its accomplishments did not prevent him from demanding that it hold a mirror to its face and probe for intensity and depth.

Finally, the shallowest cut of all is the attempt to pigeonhole the Rav within the confines of a current narrow “camp.” At the recent Edah conference, a paper decrying right-wing revisionism concerning the Rav was widely circulated. Surely, however left-wing revisionism—in the form of convenient conjectural hypotheses regarding what would have been his position with respect to certain flashpoints—is no less deplorable. Had the Rav been compelled to choose between what Ms. Kessler describes as “the fervently Orthodox yeshiva world” and its denigrators, there is not a shadow of a doubt as to what his decision would have been. The point is, however, that he did not want to make that choice, and he did not need to make it. He sought, as we should, the best of the Torah world and the best of modernity. For decades, sui generis sage that he was, the Rav bestrode American Orthodoxy like a colossus, transcending many of its internal fissures. Let us not now inter him in a Procrustean sarcophagus.

And this brings us back to our parsha and the death of Moshe.

In the final retelling of Moshe’s death, the authorship of the final eight verses is in dispute.

Rabbi Soloveitchik explains that this is why Moshe was crying. He wanted to be able to finish teaching the Jewish People Torah. Moshe knew the transmission of his death would not have the same qualities as the rest of the Torah, so Moshe began to cry. All he wanted was to teach the Jewish People Torah.

So what about the opinion that Yehoshua wrote the final eight verses? Why didn’t Hashem, according to this opinion, at least allow Moshe to write the final verses?

The ultimate realization of Moshe’s dream to teach the Jewish People Torah was accomplished by rendering Moshe himself unnecessary. Instead, his student wrote the final verses. A teacher is only finished teaching when their very presence is no longer needed—when the presence of the teacher continues within the lives of the students.

And this is the closing message of the entire Torah. Our teacher Moshe did not join us in the Land of Israel, but his absence is the ultimate testament to his enduring presence. The Torah of Moshe continues to reside within each of us.

And this explains the final words of the entire Torah:

וּלְכֹל הַיָּד הַחֲזָקָה וּלְכֹל הַמּוֹרָא הַגָּדוֹל אֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה מֹשֶׁה לְעֵינֵי כׇּל־יִשְׂרָאֵל׃

And for all the great might and awesome power that Moses displayed before all Israel.

What awesome powers of Moshe do these final words of the Torah refer to?

Rashi explains:

לעיני כל ישראל. שֶׁנְּשָׂאוֹ לִבּוֹ לִשְׁבֹּר הַלּוּחוֹת לְעֵינֵיהֶם שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר "וָאֲשַׁבְּרֵם לְעֵינֵיכֶם" (דברים ט') וְהִסְכִּימָה דַעַת הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא לְדַעְתּוֹ, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר "אֲשֶׁר שִׁבַּרְתָּ" (שמות ל"ד) — יִישַׁר כֹּחֲךָ שֶׁשִּׁבַּרְתָּ:

This refers to the fact that his heart inspired him to shatter the Tablets before their eyes, as it is said, (Deuteronomy 9:17) “And I broke them before your eyes” (Sifrei Devarim 357:45), and the opinion of the Holy One, blessed be He, regarding this action agreed with his opinion, as it is stated that God said of the Tablets, (Exodus 34:1) אשר שברת "Which you have broken", [which implies] "May your strength be fitting (יישר; an expression of thanks and congratulation) because you have broken them" (Yevamot 62a; Shabbat 87a).

The final words of the Torah recall one of the seemingly darkest incidents in the Torah: When Moshe broke the first set of luchos in front of the eyes of the Jewish People.

Why end on such a dark note?

The Torah ends on this note as a positive reminder that Moshe’s Torah now continues within each of us, the Jewish People. The shattering of the first set of luchos, the Beis HaLevi explains (see his Drashos 17-18), is what ensured that the transmission of the Torah in future generations would be from teacher to student rather than all written down in a book. The shattering of the first set of luchos is what made Moshe’s role as teacher permanent for all generations—Yiddishkeit would not be able to be grasped through a text. Instead, the Torah resides in the hearts and minds of the Jewish People within each generation. After the shattering of the luchos, the Torah was no longer exclusively a text—we, the Jewish People, became the primary vehicle of Torah. Toras Moshe, the teaching and traditions of Moshe, continues through the generations from teacher to student. In Moshe’s absence, we finally discover his enduring presence.

Shabbos Reads — Books/Articles Mentioned

The Diaries of Franz Kafka, 1910-1923, Franz Kafka

Unfinished Endings: Unresolved Conclusions are Quintessentially Jewish, Dovid Bashevkin

The Last Eight Pesukim in the Torah, Daniel Feldman

Memories of a Giant: Reflections on Rabbi Dr. Joseph B. Soloveitchik zt"l, Michael A. Bierman

A Glimpse of the Rav, Mayer Twersky

Check out All Parsha, where you can find weekly audio of Reading Jewish History in the Parsha, as well as other incredible presenters and amazing features that will enhance your Parsha journey!

Reading Jewish History in the Parsha has been generously sponsored by my dearest friends Janet and Lior Hod and family with immense gratitude to Hashem.

Where can I read the entire text of the letters quoted?