The accompanying shiur is available on the Orthodox Union's parsha learning app: All Parsha.

Perhaps the most ambitious fundraising campaign in Jewish history was assembling the funds and materials needed to build the Mishkan.

Everyone was required to give a little bit. But even after the basic contributions that everyone was required to give, the Jewish People were encouraged to give more.

We’ve all been there. Matching funds! We need your support! Anything you can do helps!

But here, something happened that may never again be repeated in the history of fundraising: The Jewish People were begged to stop giving.

“We have enough,” the builders said. We don’t need any more donations.

Adding to the strangeness—a fundraising campaign that stops because they have too much money?!—is the description of the Torah at the end of the campaign.

וְהַמְּלָאכָה הָיְתָה דַיָּם לְכׇל־הַמְּלָאכָה לַעֲשׂוֹת אֹתָהּ וְהוֹתֵר׃

Their efforts were enough (דים) and also left them with extra (והותר). Well, which one is it? Did they have exactly enough or did they have too much? Did they reach their goals or is this the bonus round?

My dearest friend, Rabbi Dr. Simcha Willig, shared a fascinating Ohr HaChaim with me many years ago. Ohr HaChaim resolves this contradiction—did they donate too much or just enough—by suggesting that Hashem made a miracle. The miracle, the Ohr HaChaim, explains was that everything that each person brought—even if it seemed extra—was incorporated into the building of the Mishkan. So even though they had extra, it was also just enough.

What, however, is the point of this miracle? Why not just collect whatever is necessary and return or not accept whatever was extra?

To understand this, let’s explore the fascinating history of Jewish charitable works, specifically the development of our favorite friend, the tzedaka box, also known as a pushke.

One of the most incredible scholars of Jewish history today is Professor Shaul Stampfer. If you have never heard of him, it is worth exploring his books and scholarship. He wrote an incredible book, Lithuanian Yeshivas of the Nineteenth Century: Creating a Tradition of Learning, which explores the early development of the yeshiva world. It is simply a must-read.

His other English book, both translated from the original Hebrew, is called Families, Rabbis, and Education: Traditional Jewish Society in Nineteenth-Century Eastern Europe, is a fascinating window into the social dynamics of the Jewish community in Eastern Europe. It is from his chapter in that book, “The Pushke and its Development,” that much of this essay is based upon.

Before we explore the development of the pushke, allow me to share a personal story about Professor Stampfer. In 2010, I visited Portland for my first-ever scholar-in-residence gig. I was still single and quite nervous. I put a lot of effort into my presentations. A few weeks later I got an email from Professor Stampfer. He was visiting Portland, where he grew up, and wrote to me to say that he saw my source sheets lying around and really enjoyed them. I was young, looking for guidance. That Professor Stampfer took the time to email a kind word to someone he didn’t know is an act of kindness that speaks volumes to his character and kindness.

But let’s talk about his scholarship.

A pushke, from the Polish word “puszka,” meaning box, is actually a fairly recent invention. These small boxes with a slit on top to insert a coin were popularized in the nineteenth century. Earlier methods of charitable giving relied upon communal taxation, meal assistance, selling aliyot, and house-to-house collections—nearly all of which, with the exception of taxation are still in use today. But all of these involved some measure of publicity—people would find out about the donation. The pushke, however, kept the size of the donation and even the donor’s identity much more anonymous.

Normally when people went door to door to collect money, they would only visit the wealthy. One of the most important contributions of the pushke was that it allowed the poor to participate in charity as well. A family could make small donations into their home’s tzedaka box and eventually an emissary from the organization that distributed the boxes would come to the home to collect the pushke once it was filled.

Aside from the poor, there was another demographic that the pushke served, namely women. “Women,” writes Professor Stampfer, “were the secret to the success of the pushke.” Most women went to shul infrequently—Shabbos and Yom Tov at most—and the home pushke opened up charitable opportunities within the home. Women composed special prayers to recite before putting money in the pushke. One moving prayer, recorded in Shas Techina, said as follows:

Ribbono shel olam, Master of the world—just as the pushke is made so that no one knows what is inside except for the collector who opens it to take out the money, so the heart of a person is hidden—no one knows what another person thinks.

More than anything else, what really accelerated the adoption of the pushke was increased relations between the Jews of Europe and the emerging Jewish community in Israel. Eastern European immigration to Israel began picking up in the late 18th century—first a wave of chassidim in 1765 and then a wave of students of the Vilna Gaon in 1808. Much of the early struggles in fundraising parallel issues we still see today. There were concerns that money raised for the Jewish communities in Israel was instead being used to support other local causes. Rav Shneur Zalmen of Liady, the first Rebbe of Chabad, known as the Baal HaTanya, actually signed a letter prohibiting funds raised for Israel to be used for local causes. Rav Shneur Zalmen’s steadfast support for the Jews of Israel was one of the many accusations hurled against him that eventually had him arrested as a traitor to the Russian government.

Another familiar fundraising issue was turf wars between fundraisers. Chassidim and misnagdim, aside from their roiling ideological battles, also fought over fundraising territories. In 1812, a tentative agreement was reached between chassidic and misnagdic fundraising dividing the territories of Eastern Europe. Rav Yisrael M’Shklov, one of the prized students of the Vilna Gaon was one of the signatories.

In 1813, Rav Dov Ber Schneerson, the second Rebbe of Chabad, known as the Mittler Rebbe, wrote a letter encouraging the use of the pushke in the home. This is one of the first references to the pushke, likely made soon after the innovation became popularized in Eastern Europe. The letter is quite moving. He writes:

…the placement of pushkes is a very wise practice that is advisable in my eyes because of the reason and foundation for the commandment to give charity that we have at all times. Specifically, during breakfast and dinner a person should give to a pushke that they have in their home next to their table two coins or so before eating…and specifically because the amount that is given into a pushke is hidden and the person who receives the money doesn’t know who gave it and the person who gives doesn’t know who it is for—this really fulfills the highest level of charity as outlined by the Rambam.

To this day, Colel Chabad is one of the oldest running charities in Israel—established by the first Rebbe of Chabad in 1788 and still running today!

Pushkes brought charity into the home. More and more institutions began to rely on them. The first Yeshiva to distribute pushkes was Volozhin Yeshiva. One famous Polish writer described that in every Jewish home, there were two pushkes—one for Volozhin Yeshiva and one for the Jews of Jerusalem.

When other yeshivas saw the success of pushkes, they began to distribute them as well. Not surprisingly, the administrators of the Volozhin yeshiva did not take too kindly when they saw other yeshivas mimic their fundraising tactic. There was actually a din Torah (rabbinical court case) when leaders of Volozhin Yeshiva objected to the Mir Yeshiva distributing pushkes as well—the former claiming hasagot gvul, infringing on their territory! The beis din decided, however, that every yeshiva had a right to distribute their own charity boxes. This is how, eventually, pushkes made their way to the United States in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Like many fundraising methods we see, even today, once a method is proven successful, everyone jumps on board. Who doesn’t remember the counters of old Queens pizza stores that were covered in pushkes from different organizations? Pushkes became so overwhelmingly common that in 1877, Rav Yitzchak Elchonan Spector issued a decree that only organizations who had a long-standing tradition of collecting with pushkes could distribute their pushkes.

The fascinating Hebrew work, The Chaluka, published in 1912 by Rabbi Avraham Moshe Lunz, collects many letters regarding fundraising disputes and proclamations related to the politics surrounding the pushke. Even Rav Yitzchak Elchonen Spector softened his view, later just insisting that those placing pushkes should receive prior approval from the established charities in Israel.

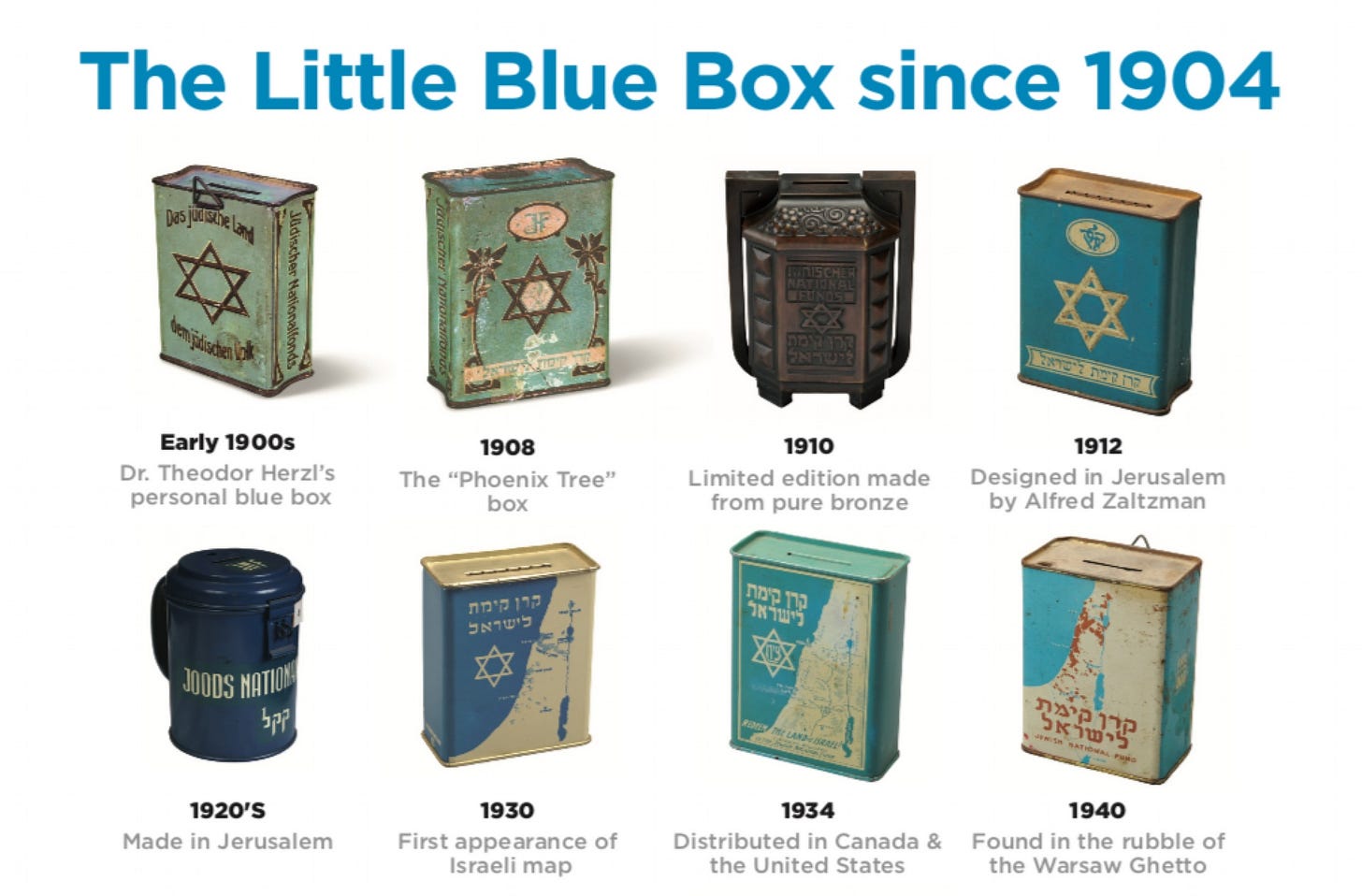

In 1897, at the First Zionist Congress, the idea was suggested to establish a central fund that would allow for the purchase of land in Israel for the emerging Zionist movement. This eventually gave rise to the Jewish National Fund and their ubiquitous blue boxes. It took a while for the Zionist movement to fully embrace the use of the pushke, perhaps because they had so long been associated with Eastern European yeshivos and pre-Zionist settlements in Israel. One rogue Galiciener named Chaim Kleinman made his own makeshift pushke to collect for the Jewish National Fund. Once others saw the success of pushkes for JNF they became wildly popular. By 1939, almost 250,000 pushkes had been distributed.

Professor Stampfer concludes his incredible article by calling attention once again to the primary force that really made the pushke what it is today: women. He writes:

The pushke was effective as a fundraising tool as long as it was integrated into a regular pattern of home ritual. By the integration of rituals involving the giving of charity by women the pushke found its place in fundraising history. In retrospect it would not be an exaggeration to claim that most of that land purchased by the Zionist movement was bought with the donations of women. Similarly, it was due to the devotion of women and not of men that the yeshivas of eastern Europe continued to exist even when the rich turned their back on them. It was due to women donors that the kolelim in Erets Yisra’el survived and even flourished…the institutions that were supported by pushkes in critical transitional years are still with us today. They survived because in critical years they could rely on the donations of countless women week after week.

Which brings us back to our parsha.

Why, the Ohr haChaim asked, did God make a miracle that even what was extra (הותר) and not needed for the building of the Mishkan was still incorporated into the final structure as if it was absolutely necessary (דים)?

The Ohr HaChaim writes something beautiful:

ואולי שישמיענו הכתוב חיבת בני ישראל בעיני המקום כי לצד שהביאו ישראל יותר משיעור הצריך חש ה' לכבוד כל איש שטרחו והביאו ונכנס כל המובא בית ה' במלאכת המשכן, וזה שיעור הכתוב והמלאכה אשר צוה ה' לעשות במשכן הספיקה להכנס בתוכה כל המלאכה שעשו בני ישראל הגם שהותר פירוש שהיה יותר מהצריך הספיק המקבל לקבל יותר משיעורו על ידי נס. או על זה הדרך והמלאכה שהביאו היתה דים לא חסר ולא יותר הגם שהיתה יותר כפי האמת והוא אומרו והותר כי נעשה נס ולא הותיר:

God was sending a message to the Jewish people that each of their individual efforts was absolutely essential in the building of the Mishkan. Even when someone came with a few coins or jewelry that wasn’t actually truly needed for the construction of the Mishkan, God wanted to show the Jewish people that all of their efforts were truly needed because each Jew is essential and our commitment is vital.

No one wants to be told that they are not needed by their community. No one wants to be superfluous. Like my dear friend Rabbi Dr. Simcha Willig always reminds me, when approached with a request, “How can I help?” No one wants to be turned away and feel unneeded and unwanted.

And much like the revolution of the pushke that democratized giving and literally supported yeshivos and the very building of the modern State of Israel, the Mishkan showed the Jewish people that there is no such thing as a superfluous Jew. Every donation was incorporated and every Jewish effort, no matter how big or small, was received as an essential part of the building of the Mishkan. A reminder that every Jew counts.

Shabbos Reads — Books/Articles Mentioned

“The Pushke and its Development” in Families, Rabbi and Education: Traditional Jewish Society in Nineteenth-Century Eastern Europe, Shaul Stampfer

The Chaluka (Hebrew), Avraham Moshe Lunz

The Colel Chabad Pushke: From the Rebbe’s Letters

Check out All Parsha, where you can find weekly audio of Reading Jewish History in the Parsha, as well as other incredible presenters and amazing features that will enhance your Parsha journey!

Reading Jewish History in the Parsha has been generously sponsored by my dearest friends Janet and Lior Hod and family with immense gratitude to Hashem.

"A pushke, from the Polish word “puszka,” meaning box, is actually a fairly recent invention. These small boxes with a slit on top to insert a coin were popularized in the nineteenth century."

The invention of the pushka is quite ancient already mentioned in Melachim ll, 12:10 and in Mishna Shekalim. However its popularization and its place in private homes might be a recent phenomenon.

Thanks for another great article.

The Ktav VeHaKabbalah has a similar interpretation of בגדי השרד--literally, "the leftover fabric".

בגדי השרד:…שרד לשון יתרון כמו שנאמר עד בלי השאיר לו שריד…והיינו לפי שנאמר ”והמלאכה היתה דים לכל המלאכה לעשות אותה והותר“. ולא נאמר מה נעשה ביתרון הזה, לכן למען חזק לב המתנדבים פן יחושו לעצמן שיהיה הנותר מוטל בבזיון ככלי אין חפץ בו מיד כאשר נצטוו אל הרמת תרומת הקדש, להפיס דעתם לזרזם הובטח להם מאז מראשית כי גם מן היתרון יעשו בגדי קדש וגם אלה יעלו לרצון לשרת בקדש, וממילא יובן כי על כן לא הוזכר בצוואת עשיית הבגדים ענין בגדי שרד, ולאשר לא נודע מתחלה שירות בגדים אלה ומה יעשה בהם לזאת עשו מן היתרון הזה מעשה אורג יריעות ישרות מבלי שום תמונת לבוש…

--הכתב והקבלה, שמות לא:י