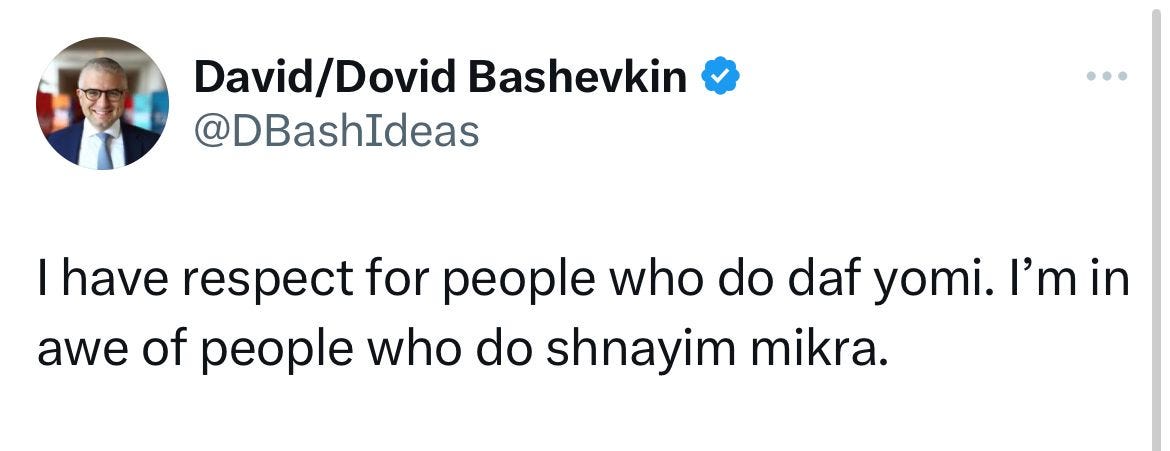

Three years ago, I began studying Daf Yomi: a page of Talmud a day in order to complete all of Talmud every seven and a half years. It rightfully gets a lot of attention. There are apps dedicated to Daf Yomi, I write an essay at the end of each tractate, and there is a well-deserved sense of heroics surrounding those committed to studying Daf Yomi each day. I don’t want to diminish that. But—and hear me out—I think we need to celebrate those who study the parsha each week.

The original Shabbos read was and always has been the weekly parsha. But the Talmud actually has a very specific way that we are supposed to review the parsha: Shnayim mikra v’echad targum—read the Torah text twice and translate once.

There is a somewhat well-known allusion to this at the beginning of Parshas Shemos. The second book of the Torah begins with the Hebrew words, “ואלה שמות בני ישראל” (And these are the names of the Jewish people) and many commentators see this beginning as an allusion to the obligation for shnayim mikra. It helps that the word שמות can also be read as an acronym for שנים מקרא ואחד תרגום.

But this leaves me with two questions:

What is exactly the point of shnayim mikra? Why read twice and translate once? Why are we told to study parsha this way? To be fair, this is not my own question. In his discussion of the laws of shnayim mikra, the Aruch HaShulchan essentially says we don’t really know the reason why. Surely there must be more to this.

Why is shnayim mikra alluded to at the beginning of Sefer Shemos? Aside from the super cute acronym, why is this the place where we find an allusion to this particular obligation? I can think of a bunch of other stories that would more neatly connect to this obligation. And I am sure with enough creativity other words could be found that would have worked equally well to build such an acronym. So why is this allusion found specifically at the beginning of Sefer Shemos?

Translation is not a matter of words only; it is a matter of making intelligible a whole culture.

— Anthony Burgess

To better understand the obligation to read twice and translate once, let’s talk a little bit about translation and its relationship to Jewish texts.

Translation is much more than just taking a word from one language and inserting a different word from another language. As Douglas Hofstadter demonstrates in his incredible book, Le Ton Beau De Marot: In Praise Of The Music Of Language, one piece of writing can be translated in an endless variety of ways. This poses a particular problem when it comes to the text of the Torah where the very language is divine. Can the Torah be translated without losing its essence?

The most comprehensive overview I have ever found on the history of Torah translations is Leonard Greenspoon’s Jewish Bible Translations: Personalities, Passions, Politics. And like any discussion of a translation of the Torah, it begins with the first translation of the Torah, the Septuagint, which was the translation of the Torah into Greek. The Talmud actually recounts this story whereby King Ptolemy separated 70 rabbis into different rooms and miraculously they all emerged with the same translation—carefully altering any potentially offensive or easily misunderstood passages. (Rav Hutner once joked that it would have been a bigger miracle if the 70 rabbis were placed in the same room and were able to emerge with a consensus on the translation!)

Much of what we know about the origins of the Septuagint derives from the “Letter of Aristeas,” which purports to be a contemporary account from the third century BCE. Some of the letter is even quoted by Josephus. The story, as told through the letter is that King Ptolemy was urged by the Chief Librarian of the magnificent Library of Alexandria to procure a translation of the Torah. The letter goes into great detail about their translator’s daily schedule and the gifts that were in turn sent to the Beis Hamikdash. It is a fascinating letter but later scholars have cautioned that it should be taken with a grain of salt. Much of the letter may have been written centuries later and it clearly is trying to assert that the status of the Septuagint should be immutable. The letter ends with a curse upon anyone who adds or deletes anything from the Greek translation.

In many ways, the Septuagint set the stage for all future translations and the enduring hesitation the Jewish community has had with the act of translation itself.

English translations of the Torah did not bode much better. The first person to translate the Bible into English was William Tyndale. But as detailed in Rebecca Romney’s fun book Printer’s Error: Irreverent Stories from Book History, the Church did not look kindly at English translations of the Bible. Tyndale spent much of his life as a fugitive and was eventually burned at the stake. But it was Tyndale’s translation that eventually paved the way for the most famous rendition of the Bible into English: the King James Bible. Printed just 75 years later, over 75% of the King James Version (KJV) was based on Tyndale’s translation. Christian influence is not hard to detect in the KJV translation but, as Robert Alter writes in his work The Art of Bible Translation, was its “inspired literalism.” They believed in the sanctity of the text of the Bible and therefore one should not “play games with God’s words.”

Of course, modern times have seen an explosion of markedly Jewish translations of the Torah—from Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan’s The Living Torah, the Artscroll revolution, and Koren’s brilliant additions to the art of translation.

Still, hesitancy for translation remains—perhaps not as much as it should.

There is a letter from Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, preserved in his collected letters, Community, Covenant, and Commitment, that I think articulates the necessary concern that Torah translations should evoke.

In 1953, Rabbi Soloveitchik was asked about the RCA’s participation in the Jewish Publication Society’s effort to produce a new translation of the Torah. The JPS wanted to form an interdenominational committee to oversee the project.

Rabbi Soloveitchik, ever gracious, explained that he could not sanction such participation. His concern, he explained, was that the translation would need “to satisfy the so-called modern scientific demands for a more exact rendition in accordance with the latest archeological and philological discoveries.” Allowing for the influence of critical Biblical studies was not something that “we, representatives of Torah sh-be-al peh [the Oral Torah], can lend our name to such an undertaking.”

And what if all of the other major Jewish rabbinic bodies participate? Would it not feel strange if Orthodox Jewry were left out of this endeavor? Rabbi Soloveitchik did not mince words in response to this question. He writes:

I noticed in your letter that you are a bit disturbed about the probability of being left out. Let me tell you that this attitude of fear is responsible for many commissions and omissions, compromises and fallacies on our part which have contributed greatly to the prevailing confusion within the Jewish community and to the loss of our self-esteem, our experience of ourselves as independent entities committed to a unique philosophy and way of life. Of course, sociability is a basic virtue and we all hate loneliness and dread the experience of being left alone. Yet at times there is no alternative and we must courageously face the test.

In the very same letter, Rabbi Soloveitchik addresses a different point, which I think actually relates even more directly to the larger role of translation in Jewish thought. In 1954, there was a push for American Jewish communities to set aside a specific Shabbos to commemorate the tercentenary of Jewish community in the United States, which began in 1654 when Asser Levy and a group of 23 Sephardic Jews fled Brazil, for New Amsterdam to seek refuge from the Portuguese Inquisition. It was a moving idea, but one which Rabbi Soloveitchik raised concerns about. He writes:

As to the Thanksgiving Sabbath set aside by the Tercentenary Committee, I must say that such action is very disturbing for two reasons. First, traditional Judaism looks askance upon synthetic prayers and artificial services. We should avoid as much as possible the arbitrary proclamation of a day of prayer and supplication which is typical of religion whose supreme authority rests with a hierarchy.

This concern, I believe, relates even more centrally to the role and concerns related to translation. Here, Rabbi Soloveitchik is not concerned about translation in the classical sense—taking words from one language and rendering them into another—but a deeper form of mistranslation—the translation of experience. A Jewish celebration cannot be simply translated into the typical language and programmatic sensibilities of American societies. A religious celebration cannot be declared in the same way the government might dedicate a day of remembrance or erect a new street sign. Imposing American sensibilities, however noble, onto Jewish ritual would be, in effect, a mistranslation.

For Rebbe Nachman the light of translation is the possibility of the 'essence' undergoing a process of change so significant that it can now be found in the 'inessential', yet through some impossible power it retains its 'essential' nature.

—R’ Joey Rosenfeld, based on Likkutei Moharan #19

Let’s return to shnayim mikra. We are told to read twice and translate once. We are not simply translating, many commentaries explain, but we are recreating the giving of the Torah itself. When the Torah was given, it was first given at Sinai to Moshe, it was then repeated to the people, and the people then “translated” and perpetuated the values of Torah within each generation. Translation—the ability to remain connected to an original text regardless of language—actually highlights the immutability of Torah. Remaining connected to Torah regardless of language, society, or circumstance, writes Maharal, allows us to connect to the Torah ideas that transcend language itself. The translation embodies the highest form of Torah: the one that lives within our hearts and minds.

And this may be why the initiative for shnayim mikra is couched in the story of the Jewish people descending to Egypt. We were entering a new society and an antagonistic culture. How can we remain tethered to our values under such circumstances? The answer of course is through translation. Whenever the Jewish people descend into the Egypts of our lives, we have the reminder of shnayim mikra. No matter the place, no matter the circumstances, the power of translation ensures we can always remain tethered to the original.

We are about to begin an exciting journey—reading twice, translating once. And I hope the connections and ideas we share here serve as a translation of sorts for our collective lives. A reminder that the ideas of Torah continue to endure and reverberate through our history.

Shabbos Reads — books/articles mentioned in this email

Jewish Bible Translations: Personalities, Passions, Politics, Leonard Greenspoon

Le Ton Beau De Marot: In Praise Of The Music Of Language, Douglas Hofstadter

Printer’s Error: Irreverent Stories from Book History, Rebecca Romney

The Art of Bible Translation, Robert Alter

Community, Covenant, and Commitment: Selected Letters and Communications: Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik

Check out All Parsha, where you can find weekly audio of Reading Jewish History in the Parsha, as well as other incredible presenters and amazing features that will enhance your Parsha journey!

Reading Jewish History in the Parsha has been generously sponsored by my dearest friends Janet and Lior Hod and family with immense gratitude to Hashem.

"As to the Thanksgiving Sabbath set aside by the Tercentenary Committee, I must say that such action is very disturbing for two reasons. First, traditional Judaism looks askance upon synthetic prayers and artificial services. We should avoid as much as possible the arbitrary proclamation of a day of prayer and supplication which is typical of religion whose supreme authority rests with a hierarchy."

With all due respect to the Rav, the Rav seems to be a making a lot of assumptions about "traditional Judaism" here that are somewhat contradictory to known history. The S&P community of the US celebrates Thanksgiving as a "local Purim," complete with a reading of the "Megillat Washington," and that is not the only "local Purim" in the world; Jewish communities across history established local Purims, such as Frankfurt's Purim Vinz, or Purims in Yemen, Italy, Vilna, and elsewhere. Kabbalat Shabbat is one of the most popular services, and it's full of "synthetic prayers," if by "synthetic," he means "post-Talmudic." Speaking of which, Kabbalat Shabbat is also an "artificial service," if by "artificial" he means "post-Talmudic." And of course his own Modern Orthodox movement has accepted new holidays.