Rising From Ashes: The Mishkan of Pekudei and Post-Holocaust Synagogue Reconstruction

Shani Taragin on Parshas Pekudei

We’re excited to share that Reading Jewish History in the Parsha will now feature past 18Forty guests as guest writers. Each week, they’ll bring their unique insights on how Jewish history connects with the weekly Torah portion.

This week, we are honored to welcome Rabbanit Shani Taragin, who joined us on the 18Forty podcast alongside her husband, Rav Reuven Taragin, for our extensive series on “Israel at War.” More recently, she joined us on the 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers podcast for a discussion about Israel, the hostage deal, and messianism.

Rabbanit Shani is a noted author and teacher in Israel and worldwide. She currently serves as rosh beit midrash for the women in Yeshiva University’s new academic program in Israel; on the advisory committee for the Mizrachi Olami Shalhevet program; as educational director for Mizrachi Olami alongside her husband; and as the educational director of Matan Eshkolot.

From Breach to Restoration: The Enduring Pattern of Jewish History

In the final moments of Sefer Shemot, we witness the culmination of a remarkable journey. Parshat Pekudei tells of the completion of the Mishkan, that sacred dwelling place meticulously constructed according to divine specifications. The text is marked by precision, accounting for every piece of gold, silver, and copper donated, every thread woven, every plank secured. But underlying this inventory lies a profound narrative of restoration after breach, of healing after rupture.

As Rashi notes (Shemot 38:21), the Mishkan is called "Mishkan HaEdut"—the Tabernacle of Testimony—because it stands as eternal testimony that Hashem had forgiven Israel after the devastating breach of the Golden Calf. In the wake of that spiritual catastrophe, when the newly liberated nation had faltered so dramatically at Sinai's foot, the Mishkan emerged not merely as a structure but as the physical embodiment of divine reconciliation.

This pattern—breach, devastation, and then painstaking rebuilding—repeats throughout Jewish history with haunting consistency. Perhaps nowhere is this pattern more starkly visible than in the post-Holocaust reconstruction of Jewish life, particularly through the rebuilding of synagogues across Europe, Israel, and the Americas during 1945-1960s.

The Accounting of Loss and the Inventory of Renewal

Parshat Pekudei opens with an accounting: "These are the records of the Mishkan, the Mishkan of Testimony, which were recorded at Moses' command" (Shemot 38:21). This meticulous inventory seems, at first glance, merely administrative. Yet it reveals something profound about how sacred space is established—through conscious recording, through naming what was lost (particularly as Nachmanides notes, the misuse of gold in sin, and now properly channeled) and what has been restored.

After the Holocaust, Jewish communities faced an accounting of their own—one almost too devastating to contemplate. Six million Jews murdered. Thousands of synagogues destroyed across Europe. Sacred Torah scrolls desecrated. Ritual objects looted or burned. Communities erased. The ledger of loss was beyond comprehension.

Yet amid this accounting came another form of record-keeping: the documentation of what could be recovered, what could be rebuilt. Like the detailed inventories of Pekudei, survivors and Jewish organizations began the painstaking work of tracking down stolen Judaica, documenting destroyed synagogues, and cataloging the remnants of religious life that might form the seeds of renewal.

The Jewish Museum in Prague houses silver Torah crowns and pointers gathered from destroyed Czech synagogues. The Jewish Cultural Reconstruction committee, led by figures like Salo Baron and Hannah Arendt, worked to redirect hundreds of thousands of heirless Jewish books and objects to new Jewish communities. This accounting—both of what was lost and what might be reclaimed—echoes the careful inventories of Pekudei, recognizing that before renewal can begin, we must first document what was and what remains.

The Synagogue as Testimony of Forgiveness

Rav Shmuel Berenbaum zt"l (March 13, 1920-January 6, 2008), rosh yeshiva of Mir yeshiva, born in Knyszyn, Poland 1920, studied at Ohel Torah Yeshiva in Baranowicze, led by Rabbi Elchonon Wasserman. At the onset of World War II, he traveled with the Mir Yeshiva to Vilna, Curaçao, and to Kobe, Japan, where they remained for seven months before being settled by the Japanese government in Shanghai, China. Following the war, Rav Berenbaum ( who traveled with the remnants of the Mir Yeshiva to the US, becoming rosh yeshiva of the "rebuilt" Mirrer yeshiva in 1964) teaches in his sefer, Tiferes Shmuel, that the Mishkan was far more than mere testimony of forgiveness after the Golden Calf. It served as the means of drawing close again, of recreating loyalty, and functioning as the foundation of reconciliation. The Mishkan was the physical sign that the relationship between God and Israel could move forward despite the breach.

The synagogues that rose from the ashes of the Holocaust carried this same multidimensional purpose. They were not merely buildings of brick and stone but testimonies that Jewish life could continue, that a relationship with God remained possible even after the greatest darkness.

Consider the Nozyk Synagogue in Warsaw—the only synagogue in the city to survive the war, though heavily damaged. Its restoration and reopening in 1983 stood as powerful testimony that Jewish prayer could again rise from Polish soil. Or the New Synagogue in Dresden, Germany, destroyed during Kristallnacht in 1938, and finally rebuilt and rededicated in 2001—a gleaming dome of copper and glass testifying that reconciliation was possible even in the very country and nation that had orchestrated the Holocaust.

These reconstructed synagogues served as what the prophet Yechezkel called the "Mikdashei Me'at" (small sanctuaries), symbolizing God's presence in exile, and what the Jewish philosopher Emil Fackenheim expressed as the embodiment of the 614th commandment—the commandment not to grant Hitler posthumous victories by abandoning Judaism. Each rebuilt synagogue made concrete the audacious claim that forgiveness—even after the unforgivable—might somehow be achieved, that reconciliation remained redeemable, and that the covenant between God and Israel endured even through the valley of deepest shadow.

The Pre-War Context: Judaism at the Brink

To understand the full significance of post-Holocaust synagogue reconstruction, we must acknowledge the precarious state of Judaism in many parts of Europe even before the war. The 19th and early 20th centuries had witnessed unprecedented levels of assimilation among European Jews. Enlightenment values, secularization, and the promise of civil equality led many Jews away from traditional observance.

In Germany, Reform Judaism had dramatically transformed worship, with many congregations abandoning Hebrew prayer, traditional observances, and messianic hopes in favor of integration with European culture. In Eastern Europe, growing numbers of Jews were embracing secularism, socialism, and Zionism as alternatives to traditional religious life. The massive waves of immigration to America further disrupted established communities.

The Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment) had opened doors to secular education and professional advancement but had also created generations of Jews increasingly disconnected from traditional learning and practice. By the 1930s, many observers feared for Judaism's future in the diaspora—not because of physical threat, but because of internal dissolution.

It was into this already fragile context that the Holocaust struck—not only destroying communities physically but threatening to sever the transmission of tradition entirely. The few who emerged from the death camps often found themselves the last remaining practitioners of particular customs, the sole inheritors of specific melodies, the final repositories of ancient traditions.

Pakod Yifkod: The Promise of Redemption

In the word "pekudei" itself we find a profound connection to Jewish memory and redemption. The root p-k-d carries connotations of remembering, accounting, and assigning. It appears in one of the most significant phrases in Jewish history in the final verses of Sefer Bereishit (50:25): "pakod yifkod"—"God will surely remember you"—the coded message of redemption that Joseph entrusted to his brothers, promising eventual deliverance from Egyptian exile.

Centuries later, when Moshe approached the enslaved Israelites, he invoked this very phrase as proof of his divine mission. The words "pakod pakadeti”—"I have surely remembered you,” recorded at the opening of Sefer Shemot (3:16)—signaled that the promised redemption had finally arrived. This linguistic connection between accounting, remembering, and redemption runs like a golden thread through the conclusion of Sefer Shemot in Parshat Pekudei and Jewish history more broadly.

For Holocaust survivors, the reconstruction of synagogues represented a modern fulfillment of "pakod yifkod"—the divine promise that God would remember His people even after catastrophe. Each cornerstone laid, each Torah scroll restored, each melody reclaimed echoed this ancient assurance that exile would not be permanent, that divine remembrance would ultimately lead to restoration.

This understanding transformed the physical work of synagogue reconstruction into spiritual labor with messianic dimensions. The survivors who painted synagogue walls, transported and restored old arks, crafted new arks, and transcribed Torah scrolls were not merely rebuilding buildings but enacting redemption, participating in a divine accounting that would ultimately balance the ledgers of history.

The Synagogue as Mikdash Me'at: Creating Sacred Space

Like the Mishkan in Parshat Pekudei, each post-Holocaust synagogue served as a small sanctuary, a miniature version of the Temple where divine presence might dwell among the people. For communities rebuilding after devastation, this concept took on urgent new significance.

The closing verses of Pekudei describe how God's presence filled the completed Mishkan: "Then the cloud covered the Tent of Meeting, and the glory of the Lord filled the Tabernacle" (Shemot 40:34). This divine indwelling represented the ultimate healing after the breach of the Golden Calf—God had not only forgiven but had drawn close again, choosing to dwell among an imperfect people.

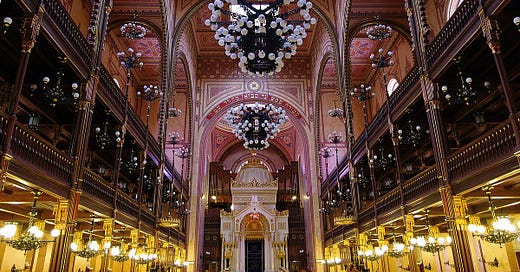

Similarly, the post-Holocaust synagogue became the primary site where surviving Jews could experience divine presence amid the wreckage of history. The Dohány Street Synagogue in Budapest (the largest in Europe, restored in the 1990s), the Nozyk Synagogue in Warsaw (the only Warsaw synagogue to survive the war), and the Park East Synagogue in New York (which became home to many survivors)—all became places where the experience of divine presence could somehow be reclaimed after the horror of "divine absence" that Elie Wiesel and others had testified to witnessing in the death camps.

The synagogue offered a revolutionary response to the theological crisis of the Holocaust. If Auschwitz raised the question of where God was during humanity's darkest hour, the rebuilt synagogue offered not an intellectual answer but an experiential one—here, in this sacred space, divine presence could be felt again through prayer, community, and ritual.

The Universal Invitation: From Vayikra to Modern Welcome

Parshat Pekudei concludes Sefer Shemot, immediately followed by Sefer Vayikra, which begins with God calling to Moshe from the newly completed Mishkan. This literary connection reminds us that the purpose of the Mishkan was not merely its construction but its function—to serve as the place where every Israelite, regardless of status, could approach God through sacrifice and prayer.

The opening of Vayikra—"And He called to Moses"—initiates this universal invitation. The sacrificial system detailed in the following chapters democratized spiritual access, providing pathways for every person to seek atonement, express gratitude, and draw near to the divine.

The post-Holocaust synagogue embodied this same spirit of universal invitation at a moment when it was desperately needed. In a world where Jewish identity had been grounds for extermination, the rebuilt synagogues flung open their doors with radical hospitality. They became spaces where Jews of all backgrounds—secular and religious, Ashkenazi and Sephardi, European-born and American-raised—could reconnect with tradition on their own terms.

Consider the story of the Lincoln Square Synagogue in New York, founded in 1964 by Holocaust survivors and American Jews. Under Rabbi Shlomo Riskin's leadership, it pioneered a welcoming approach that made traditional Judaism accessible to Jews with limited religious backgrounds. With classes for beginners, explanatory services, and an atmosphere of inclusion, it embodied the spirit of Vayikra's universal invitation.

Or look at the Crown Heights Jewish community in Brooklyn, where Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidim—many of whom had fled Europe during the Holocaust—developed revolutionary outreach methods centered on the synagogue as a welcoming space. The Lubavitcher Rebbe's emissaries established synagogues worldwide with a singular mission: to create spaces where every Jew, regardless of background or knowledge, could reconnect with their heritage.

This radical hospitality was not merely strategic but theological—rooted in the belief, expressed in the transition from Pekudei to Vayikra, that sacred space exists to facilitate relationships. The meticulously accounted Mishkan of Pekudei finds its purpose in the universal invitation of Vayikra. Similarly, the carefully reconstructed post-Holocaust synagogues found their purpose not in architectural splendor but in their function as gateways of return for disconnected Jews.

From Accounting to Encounter

As we reflect on Parshat Pekudei alongside the post-Holocaust reconstruction of Jewish life, we discern a profound pattern: Meticulous accounting serves as a prelude to a transformative encounter. The detailed inventories of the Mishkan's materials prepare the way for divine indwelling. Similarly, the careful documentation of Jewish losses after the Holocaust prepared the way for a renewed encounter with tradition, community, and God.

The word "pekudei" itself points to this progression—from accounting to presence, from remembrance to redemption. When Moshe completed the inventory of the Mishkan's materials, the divine glory descended. When Jewish communities completed their accounting of what remained after the Holocaust, a different kind of presence emerged—not the visible cloud of glory described in Shemot, but the palpable presence of a tradition reborn against impossible odds.

The synagogues built after the Holocaust stand as modern-day "Mishkanot HaEdut" – tabernacles of testimony. They testify not only to what was lost but to what has been reclaimed, not only to historical trauma but to theological resilience. Like the original Mishkan, they testify that breach is never the end of the story, that divine-human partnership continues, and that sacred space can always be rebuilt—even from ashes.

In our generation, as direct memory of the Holocaust fades, yet as modern Oct. 7 pogroms and antisemitism resurface, these synagogues and the communities they house become even more precious as testimonies. They remind us that the Jewish story is one of persistent rebuilding, of sacred accounting, and of the audacious faith expressed in the words that connect Joseph's promise to the Mishkan's completion to our modern moment: "pakod yifkod"—God will surely remember, and redemption will surely come. Chazak chazak venitchazek!

A small correction, as far as I understand it nobody actually went to Curaçao, they just needed a document for travel through the Soviet union.