The accompanying shiur is available on the Orthodox Union's parsha learning app: All Parsha.

For a book called “Names,” Sefer Shemos seems to be sorely lacking in them.

When we are first introduced to Moshe, the Torah seems to go out of its way to keep everyone involved anonymous.

Here is how the Torah first describes Moshe’s parents:

A certain member of the house of Levi went and took into his household as his wife a woman of Levi.

The names of Moshe’s parents? Sefer Shemos, the Book of Names, does not say a word.

Even earlier, when Moshe’s midwives are introduced, the Torah does not introduce them by their real names.

The king of Egypt spoke to the Hebrew midwives, one of whom was named Shiphrah and the other Puah.

Rashi, of course, identifies the real names of the midwives: Yocheved and Miriam, Moshe’s respective, mother and sister.

Again, the book of names, and we are left nameless.

Why is the Torah’s recounting of the birth of Moshe, the most important Jew in Jewish history, missing the names of all those involved?

And why does the Book of Names, Sefer Shemos, begin without names?

To understand all of this let’s explore how the actual portrait of Moshe has been depicted through the ages.

Michelangelo’s Moses

In 1505, Pope Julius II commissioned Michelangelo to build his tomb. It took Michelangelo 40 years to complete—decades after Julius’s 1512 death.

The finished product has become iconic. Nearly eight-feet tall, at the center of the tomb is a sculpture of Moses.

The sculpture is captivating. As Rabbi Benjamin Blech and Roy Doliner explain in their captivating book, The Sistine Secrets: Michelangelo’s Forbidden Messages in the Heart of the Vatican, Michelangelo deliberately spaced Moses’s eyes too far apart, a technique he also uses in his sculpture of David. “He made the eyes slightly too far apart, extra deep, and not focused on the viewer,” they explain. “As you stare at the Moses statue today, no matter where you stand, you realize that he is not looking at you,” they write, “That’s because his gaze is fixed firmly on the future.”

They were not the only ones to be captivated by Michelangelo’s Moses.

In 1914, Sigmund Freud published an essay entitled “The Moses of Michelangelo,” that analyses the sculpture. Freud admits that he is not a professional art critic, yet something about the sculpture—or more likely, Moses himself—captivates him. Freud offers a fascinating thesis: Michelangelo did not depict the Moses of the Bible but rather an alternative history of Moses where he does not end up breaking the luchos (tablets) upon seeing the Jewish people worshipping the Golden Calf. As Freud writes:

What we see before us is not the inception of a violent action but the remains of a movement that has already taken place. In his first transport of fury, Moses desired to act, to spring up and take vengeance and forget the Tablets; but he has overcome the temptation, and he will now remain seated and still, in his frozen wrath and in his pain mingled with contempt. Nor will he throw away the Tablets so that they will break on the stones, for it is on their especial account that he has controlled his anger; it was to preserve them that he kept his passion in check. In giving way to his rage and indignation, he had to neglect the Tablets, and the hand which upheld them was withdrawn. They began to slide down and were in danger of being broken. This brought him to himself. He remembered his mission and for its sake renounced an indulgence of his feelings. His hand returned and saved the unsupported Tablets before they had actually fallen to the ground. In this attitude he remained immobilized, and in this attitude Michelangelo has portrayed him as the guardian of the tomb.

His essay includes drawings to highlight how Michelangelo could have depicted Moses—either more serene or more agitated—but clearly chose not to.

This, of course, is not the story depicted in the Bible. In the 34th chapter of Sefer Shemos, Moshe does smash the luchos. Freud acknowledges that his interpretation departs from scripture:

But here it will be objected that after all this is not the Moses of the Bible. For that Moses did actually fall into a fit of rage and did throw away the Tablets and break them. This Moses must be a quite different man, a new Moses of the artist’s conception; so that Michelangelo must have had the presumption to emend the sacred text and to falsify the character of that holy man.

Freud’s interpretation of Michelangelo tells us more about Freud than it does Michelangelo, to say nothing of Moses. Freud was nearly obsessed with the personality of Moshe, which he returned to in his final published work before his death, Moses and Monotheism. As Yosef Chaim Yerushalmi discusses at length in his book, Freud’s Moses: Judaism Terminable and Interminable (of which we have mentioned and will most likely return) Freud saw his father in Moses, and as he aged he began to look like his father and saw himself in Moshe’s image as well.

Reportedly, when Michelangelo finished the sculpture, it was so captivatingly real, the artist grabbed it by the shoulders and said to his creation, “Speak, damn it, speak!”

One enduring issue many have raised in reaction to Michelangelo’s Moses is the presence of horns on the head of Moses. Are the horns residual antisemitism, depicting Jews as demonic, a poor translation of the word keren used to describe Moshe (Ex. 34:29), or something else entirely?

At the end of the fourth century CE, St. Jerome translated the entire Bible into Latin, a translation now known as the Vulgate. The most obvious explanation for the horns on Michelangelo’s Moses is the poor translation of the Hebrew word keren that appears in the Vulgate. As Stephen Bertman argues in his article, “The Antisemitic Origin of Michelangelo’s Horned Moses,” this was not just an error in translation. “Rather than representing an innocent "mistake' as many have claimed,” Bertman writes, “the horns of Michelangelo's Moses actually symbolize—and serve to perpetuate—a legacy of antisemitism that stretched from antiquity to the Renaissance.”

Not everyone sees such nefarious motives behind Michelangelo’s horns.

The Moses in the tomb was not the original plan. Originally Moses was supposed to adorn the tomb of Julius II from much higher ground. Michelangelo’s original plan had to be reworked as it was far too expensive and impractical. And, as Blech and Doliner argue, Michelangelo created horns for Moses in the hopes that from the elevated perch of the sculpture, the horns would be invisible and just refract light creating the illusion of light emanating from his head, exactly as described in the Bible.

Michelangelo was hardly antisemitic, as they argue throughout the book. In fact, his art betrays more of an anti-church bias. Instead, they explain, “the artist has planned Moses as a masterpiece not only of sculpture, but also of special optical effects worthy of any Hollywood movie.”

Rembrandt’s Moses

Just over a century after Michelangelo completed his sculpture, Rembrandt completed his work, “Moses Breaking the Tablets of the Law,” in 1659.

He did not repeat Michelangelo’s controversial decision to depict Moses with actual horns. Instead, Moses’s face is seen glowing. Additionally, Moses is holding two tablets—consistent with the Biblical description. The Hebrew words on the tablets are both legible and generally correct.

Rembrandt’s fealty within his painting to biblical and, more notably, rabbinic accuracy, is no doubt attributable to his warm relationship to the Jews of Amsterdam, most notably to Menasseh ben Israel. As Steven Nadler masterfully argues in his work, Rembrandt’s Jews, the artist relied upon his relationship with Menasseh ben Israel to accurately portray Biblical scenes, as interpreted through rabbinic literature. Perhaps the most notable example of this is Rembrandt’s work Belshazzar's Feast, which depicts the scene in the fifth chapter of Daniel through the rabbinic interpretation offered in the Babylonian Talmud (Sanhedrin 22a).

As Nadler writes:

Whatever the circumstances of their initial meeting, what probably brought the two men together, in the end, was need. Rembrandt’s need. He wanted to get the details right. Menasseh, perhaps more than anybody—with his easy ability to explain matters Jewish to non-Jews, and with his knowledge of rabbinic literature, mysticism, and messianism—could help him. Right down to the serif of the aleph.

As Shalom Sabar writes in his article, “Between Calvinists and Jews: Hebrew Script in Rembrandt’s Art,” the artist’s interaction was a glimpse into a more peaceful coexistence and mutual enlightenment that, at times, modernity brought. “At best it allowed for a better knowledge of the other,” Sabar writes, “closer interaction and an exchange of ideas, all of which reflects a rather improved and tolerant approach to Jews and Judaism.”

Menasseh ben Israel, who hoped to bring a messianic reconciliation through his work looked at these forms of collaborations as a glimpse towards a Christian reevaluation of their relationship towards the Jewish People. As he writes in his work Mikveh Yisroel:

So at this day we see many [Christians] desirous to learn the Hebrew tongue of our men. Hence may be seen that God has not left us; for if one persecutes us, another receives us civilly and courteously.

Rabbi Yisroel Lipschutz’s Moses

Controversies around depictions of Moshe were not limited to gentile portraits. A different storm brewed around the image of Moshe but this time the source was not a painting but a legend repeated in a rabbinic commentary on the Mishnah.

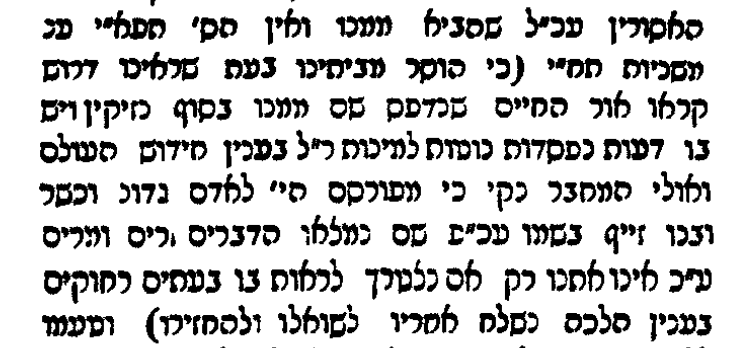

In Rabbi Yisroel Lipschutz’s masterful commentary on the Mishnah, Tiferes Yisroel, he quotes the following legend:

After Moshe redeemed the Jewish people from Egypt an Arabian King sent an artist to paint Moshe’s portrait. When the Arabian King received the portrait he asked one of his advisors who was an expert in analyzing an individual’s characteristics based on the facial patterns to look at the portrait of Moshe. The report of this expert was very unflattering. Moshe, the expert explained, possessed terrible personal traits—he was greedy, arrogant, and unkind. The Arabian King was shocked. He thought something must have been wrong with the portrait, so he set out to meet Moshe himself. When he met Moshe, he saw the portrait was correct. How could this be? Moshe himself explained that he did indeed possess these unseemly natural characteristics but through his self-discipline and self-development he managed to overcome them.

As Professor Shnayer Leiman explains in his classic treatment of this legend, “R. Israel Lipschutz: The Portrait of Moses,” this commentary created quite a controversy.

Broadsides decried the disrespect this legend displayed for our teacher, Moshe. Rabbi Eliyahu Dovid Rabinowitz-Tuemim, the father-in-law of Rav Kook, said it was poor judgment to include this story, which he asserts came from pagan myths.

His critics were not wrong, as Professor Saul Lieberman has shown the legend actually originates from the Greco-Roman period but it was not originally about Moshe—the original version was about Socrates!

The Tiferes Yisroel, while a classic, did not escape controversy. In a responsa of the Munkatcher Rebbe, Sheilos U’ Teshuvos Minchas Elazar #64, he references the commentary but adds that he does not have the work in his home—after he saw some of the more iconoclastic ideas in the work he removed it from his house. He even suggests that his son may have added in forged commentaries!

We do not know what the face of Moshe actually looked like, but the attempts throughout the centuries to depict his likeness have garnered a great deal of controversy. Ultimately the search for Moshe’s portrait has yielded a portrait of the relationship between art and the Jewish community through the ages.

Moshe’s parents and midwives are all introduced anonymously.

This, explains Maharal, was not an accident.

Moshe represents a transcendent redemption that is beyond any specific upbringing, parents, or delivery. He was the destined redeemer of the Jewish people. His parents’ names are absent to emphasize that the redemption he represents transcends his specific parents or delivery.

And Moshe in a larger sense represents the transformation of every Jew throughout Sefer Shemos. The Book of Names begins nameless. Within the exile of Mitzrayim, we are but cogs in a larger machine—products of an enslaved system that obscures our individual purpose. Moshe, the redeemer of the Jewish people and each of us, rises above this form of subjugation and reminds the Jewish people to rediscover our individual names and purpose.

Through Moshe’s name and portrait, we are given the strength to discover our own.

Shabbos Reads — Books/Articles Mentioned

The Sistine Secrets: Michelangelo’s Forbidden Messages in the Heart of the Vatican, Benjamin Blech & Roy Doliner

The Moses of Michelangelo, Sigmund Freud

Freud’s Moses: Judaism Terminable and Interminable, Yosef Chaim Yerushalmi

The Antisemitic Origin of Michelangelo’s Horned Moses, Stephen Bertman

Rembrandt’s Jews, Steven Nadler

Between Calvinists and Jews: Hebrew Script in Rembrandt’s Art, Shalom Sabar

R. Israel Lipschutz: The Portrait of Moses, Shnayer Leiman

Check out All Parsha, where you can find weekly audio of Reading Jewish History in the Parsha, as well as other incredible presenters and amazing features that will enhance your Parsha journey!

Reading Jewish History in the Parsha has been generously sponsored by my dearest friends Janet and Lior Hod and family with immense gratitude to Hashem.

As Prof. Leiman writes, the Tiferes Yisrael most probably got this story from a chasidic sefer (fittingly) named Ohr Pnei Moshe (P. Chukas), he brings it from previous seforim but doesn’t name them. This idea, without the story, is already found in previous chasidic seforim such as Degel Machne Efraim (p. Ki sisa) and Teshuas Chein (p. Toldos) based on the gemara Bechoros 5a.

Thanks for the great article.

I first read about that Tiferes YIsrael in R Dr Abraham Twerski’s LET US MAKE MAN and it blew me away as an 18 yr old. This was a great piece on Shemos, thank you.