The Rebbe of Teshuva

On Parshas Nitzavim-Vayelech and the incredible journey of the Yabloner Rebbe

The accompanying shiur is available on the Orthodox Union's parsha learning app: All Parsha.

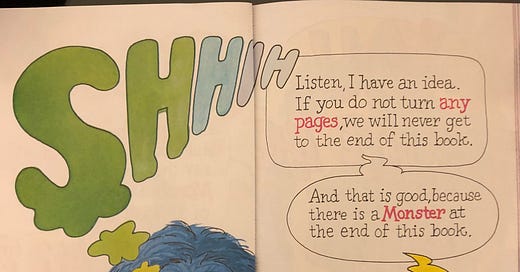

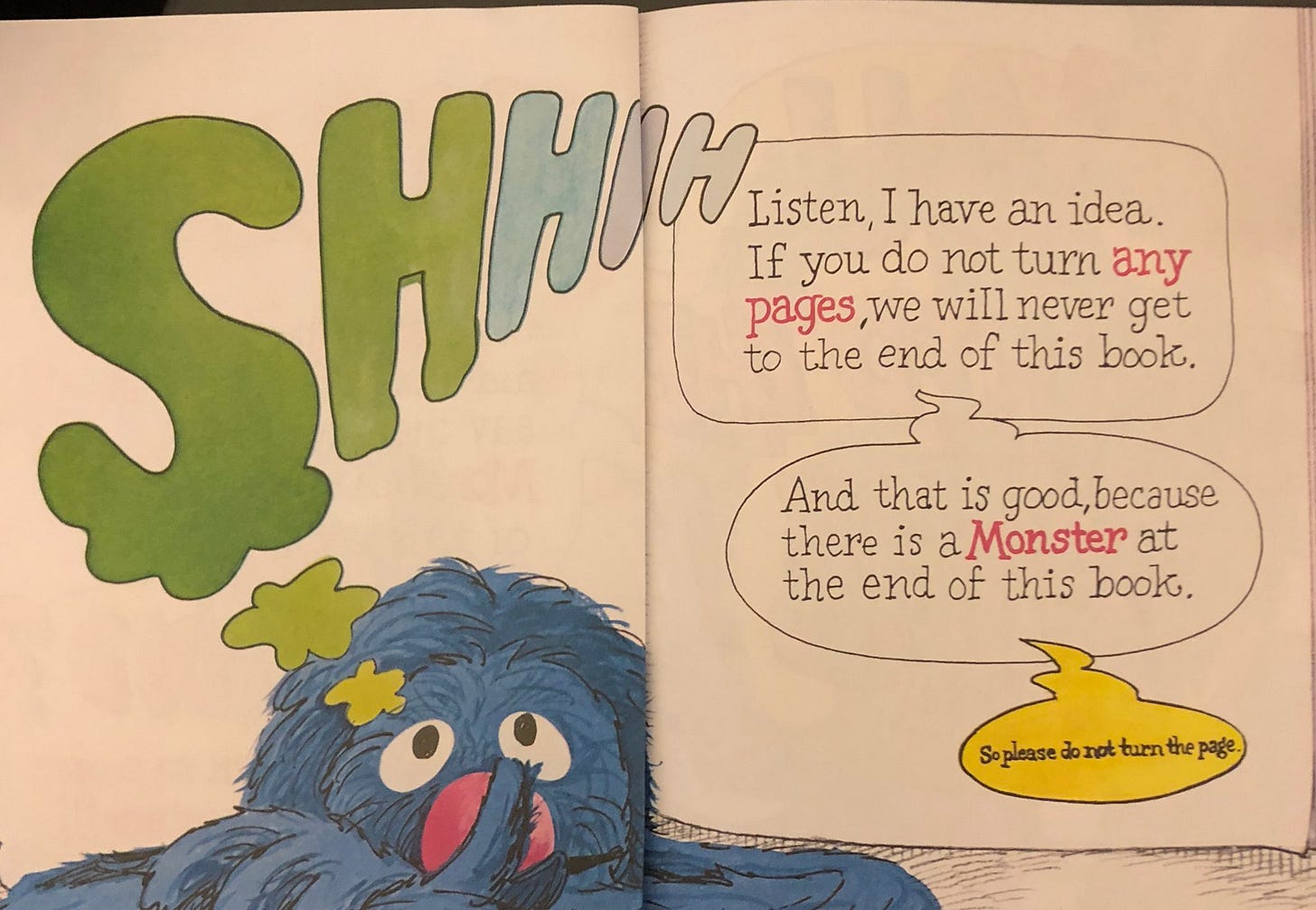

One of my favorite children’s books is called The Monster at the End of This Book. Its protagonist is the lovable, furry old Grover—the hapless character we know from his recurring role on Sesame Street.

I didn’t fully appreciate the book until I started reading it to my children. Now, it’s become my favorite to read as the High Holidays approach.

The book begins with Grover realizing what the title implies: “On the first page, what did that say,” Grover wonders. “Did that say there will be a Monster at the end of this book?” The dread starts to set in. This is not a book Grover wants to finish.

Grover does everything he can to avoid the monster. He begs the reader not to turn the page, ties down the pages, and even builds brick walls, all in the hope that he can stop the story from progressing. I’ve used similar tactics myself—distract, don’t show up, don’t pay attention—anything to avoid the monstrous experience of the High Holidays.

As the book nears its end, Grover attempts one final plea. “The next page is the end of the book, and there is a monster at the end of the book,” Grover supplicates. “Please do not turn the page—please, please, please.”

Of course, despite Grover’s protests, the reader—in my case, usually my daughter—forges ahead. And as you turn to that last ominous page waiting to be confronted by the terrifying monster the book cover portended, there is a surprise. The only person on the last page is Grover.

“Well look at that,” an astonished Grover realizes. “This is the end of the book, and the only one here is me—I, lovable, furry old Grover, am the Monster at the end of this book.” For all of his angst and fear, the only monster confronting Grover at the end of the book was himself.

As I once wrote about in an article entitled, “The Monster at the End of the Machzor,” this book always felt like an analogy for the dread leading up to the High Holidays:

As we approach the High Holidays, it can feel like that monster is coming. We think of pages left, the seat we have in shul, the guilt and shame we may have about our own Jewish lives. But the confrontation this entire period is ultimately meant to facilitate is with ourselves.

For a time that, for so many, is filled with anticipatory dread it is interesting that in fact the way our parsha describes the process of teshuva is deliberately as something accessible and easy.

The mitzvah of teshuva—assuming it even is a mitzvah—is presented as follows:

כִּי הַמִּצְוָה הַזֹּאת אֲשֶׁר אָנֹכִי מְצַוְּךָ הַיּוֹם לֹא־נִפְלֵאת הִוא מִמְּךָ וְלֹא רְחֹקָה הִוא׃

Surely, this Instruction which I enjoin upon you this day is not too baffling for you, nor is it beyond reach.

לֹא בַשָּׁמַיִם הִוא לֵאמֹר מִי יַעֲלֶה־לָּנוּ הַשָּׁמַיְמָה וְיִקָּחֶהָ לָּנוּ וְיַשְׁמִעֵנוּ אֹתָהּ וְנַעֲשֶׂנָּה׃

It is not in the heavens, that you should say, “Who among us can go up to the heavens and get it for us and impart it to us, that we may observe it?”

וְלֹא־מֵעֵבֶר לַיָּם הִוא לֵאמֹר מִי יַעֲבׇר־לָנוּ אֶל־עֵבֶר הַיָּם וְיִקָּחֶהָ לָּנוּ וְיַשְׁמִעֵנוּ אֹתָהּ וְנַעֲשֶׂנָּה׃

Neither is it beyond the sea, that you should say, “Who among us can cross to the other side of the sea and get it for us and impart it to us, that we may observe it?”

כִּי־קָרוֹב אֵלֶיךָ הַדָּבָר מְאֹד בְּפִיךָ וּבִלְבָבְךָ לַעֲשֹׂתוֹ׃ {ס}

No, the thing is very close to you, in your mouth and in your heart, to observe it.

Interestingly, it is not entirely clear which mitzvah these verses are actually talking about. Rashi seems to think it is talking about Torah. The Ramban, however, assumes it is talking about teshuva. He writes:

וְטַעַם כִּי הַמִּצְוָה הַזֹּאת, עַל כָּל הַתּוֹרָה כֻּלָּהּ. וְהַנָּכוֹן כִּי עַל כָּל הַתּוֹרָה יֹאמַר (דברים ח':א'), כָּל הַמִּצְוָה אֲשֶׁר אָנֹכִי מְצַוְּךָ הַיּוֹם, אֲבָל הַמִּצְוָה הַזֹּאת, עַל הַתְּשׁוּבָה הַנִּזְכֶּרֶת, כִּי וַהֲשֵׁבֹתָ אֶל לְבָבֶךָ (דברים ל':א') וְשַׁבְתָּ עַד ה' אֱלֹהֶיךָ (דברים ל':ב'), מִצְוָה שֶׁיְּצַוֶּה אוֹתָנוּ לַעֲשׂוֹת כֵּן. וְנֶאֶמְרָה בַּלָּשׁוֹן הַבֵּינוֹנִי, לִרְמֹז בַּהַבְטָחָה כִּי עָתִיד הַדָּבָר לִהְיוֹת כֵּן. וְהַטַּעַם לֵאמֹר כִּי אִם יִהְיֶה נִדַּחֲךָ בִּקְצֵה הַשָּׁמָיִם וְאַתָּה בְּיַד הָעַמִּים, תּוּכַל לָשׁוּב אֶל ה' וְלַעֲשׂוֹת כְּכֹל אֲשֶׁר אָנֹכִי מְצַוְּךָ הַיּוֹם, כִּי אֵין הַדָּבָר נִפְלָא וְרָחוֹק מִמְּךָ אֲבָל קָרוֹב אֵלֶיךָ מְאֹד לַעֲשׂוֹתוֹ בְּכָל עֵת וּבְכָל מָקוֹם. וְזֶה טַעַם בְּפִיךָ וּבִלְבָבְךָ לַעֲשׂוֹתוֹ, שֶׁיִּתְוַדּוּ אֶת עֲוֹנָם וְאֶת עֲוֹן אֲבֹתָם בְּפִיהֶם, וְיָשׁוּבוּ בְּלִבָּם אֶל ה', וִיקַבְּלוּ עֲלֵיהֶם הַיּוֹם הַתּוֹרָה לַעֲשׂוֹתָהּ לְדוֹרוֹת, כַּאֲשֶׁר הִזְכִּיר (דברים ל':ב'), אַתָּה וּבָנֶיךָ בְּכָל לְבָבְךָ, כְּמוֹ שֶׁפֵּרַשְׁתִּי (שם)

Which one is it? In fact, in one of the most famous stories in the Talmud, known as the Tanur shel Achnai, it seems clear that these verses are talking about Torah. In the story of Tanur shel Achnai, a rabbi tries to bring proofs to his opinion through miracles and heavenly voices. Despite the acts of wonder performed on his behalf, the other rabbi is not convinced. “The Torah is not in Heaven,” the rabbi explains, citing our parsha’s statement, לא בשמים היא.

The phrase לא בשמים היא makes sense when it applies to Torah—rabbinic interpretation is how we approach Torah, not through prophecy, but what on earth does it mean when applied to teshuva? And why do we use the same verses to seemingly discuss two vastly different topics—Torah and teshuva?

To understand all this let’s explore the incredible story of the Hasidic Rebbe who left traditional Jewish life and finally returned.

When the Zionist movement first began, most Chassidic communities were hesitant to join the effort to help settle the land. The Land of Israel was seen by many, particularly in the Hassidic community, as a place where Jewish observance would be nearly impossible—there was a strong presence of secular Jews, it was nearly impossible to earn a living, and the future seemed so unknown in the foreign Holy Land.

The Galinsky family, whose father Rav Mallen Galinsky, was the Dean of Shaalvim, has a remarkable letter from the Chortkover Rebbe written to their grandfather.

In the letter, written Rosh Chodesh Elul of 1931, the Chortkover Rebbe cautions his chassidim not to be afraid of getting involved in settling the Land of Israel. Stop complaining about the secular influences, he writes, and create communities in Israel. How else will the holy character of the Land of Israel remain intact if it is neglected by the Chassidic community?

One such Chassidic leader who did make a serious effort to settle the Land of Israel was a little known rabbi named Yechezkel Taub, the Yabloner Rebbe.

It is important to note that the details of his life, let alone the very legacy of his story may have likely been lost to Jewish history were it not for the incredible research and efforts of my friend Rabbi Pinni Dunner. I actually did an entire 18forty episode just on this remarkable story that I first discovered through Rabbi Dunner’s brilliant article, The Amazing Return of the Yabloner Rebbe.

Rav Yechezkel Taub became the Yabloner Rebbe—a Chassidus with an impressive following before the Holocaust—at the age of 24, after the untimely passing of his father. What started as a traditional and festive Chassidic community changed drastically in 1924, when, following a visit from the illustrious Rav Yeshaya Shapiro, brother of the famed Piaseczno Rebbe, the Aish Kodesh, Rav Taub was convinced to establish a Chassidic settlement in the Land of Israel.

The ambitious dream energized Rav Yechezkel Taub and his entire Chassidic community. With the help of the JNF, they purchased a large tract of farming land and prepared to build their lives in the Holy Land. Ninety Chassidic families joined Rav Taub in Israel, including the parents of eventual Chief Rabbi Rav Shlomo Goren.

At first, the arrival of a group of Chassidim from Europe was greeted with sensational enthusiasm. Dignitaries and leaders from across the spectrum visited the newfound yishuv and marveled at the site of a Chassidic farming village.

Not everyone, however, was so excited. Many secular Zionists thought it was a waste of time and resources to give untrained Chassidim so much farming land. “How dare these Hasidim from Jabłonna and Kozhnitz be allowed to immigrate to Eretz Yisrael and waste precious land,” David Ben-Gurion said at the 1925 Zionist Congress.

Soon, however, the mood dampened. Arab farmers refused to leave the land the Chassidim had purchased, and their efforts at creating sound infrastructure were plagued with disaster—bridges collapsed, malaria outbreaks, and financial turmoil.

In an effort to save the community, Rav Taub traveled to the United States to raise more money but returned to the Land of Israel without the requisite funds needed to further develop the land. Eventually, in an effort to place the community on more stable financial ground, Rav Taub worked out a deal with JNF whereby they would own and oversee the administration of the nascent farming community. The village’s name was then changed from Nachlas Yaakov, after Rav Taub’s father to Kfar Chassidim, as it is still known today.

This JNF deal led to even more problems. As members of his community in Poland began to inquire about their investment in Israel, Rav Taub had to admit that there was no longer any designated land for them—it was signed over to JNF. They accused Rav Taub of stealing their money.

In a last-ditch effort to secure enough money to pay off his debts and repossess the land he had handed over to JNF, Rav Taub traveled to the United States in 1938. He would not return to Kfar Chassidim for nearly half a century.

While he was fundraising in the States, word about the atrocities of the Holocaust began to trickle down. Most Yabloner Chassidim were murdered by the Nazis. Rav Taub was crestfallen, alone, and faced with a completely uncertain future. As Rabbi Dunner writes, he then made a drastic, unthinkable choice:

The pain was overwhelming. And moreover, where was God in all this? Did He even exist? If He did, was it not crystal clear that He had utterly abandoned the Yabloner Rebbe? So many people’s lives had been lost or devastated—and he, Yechezkel Taub, had been the agent of their destruction. His entire Hasidic sect had been wiped out, and those who remained alive in Kfar Hasidim despised him for his role in wrecking their lives.

In late 1944, as the full weight of his distressing predicament became clear, and his anger at God grew and kept on growing, the Yabloner Rebbe decided on a drastic course of action. Without Hasidim, he decided to himself, he was no longer a rebbe—a rebbe has to have Hasidim, and his Hasidim were gone…

And just like that, one day, Rabbi Yechezkel Taub—the revered Yabloner Rebbe, scion of the Kuzmir Hasidic dynasty, at one time leader of thousands of devoted followers, and trailblazing Orthodox Zionist settler—removed his yarmulke, cut off his sidelocks, shaved off his beard, quietly changed his name, and filed immigration papers to become a naturalized citizen of the United States.

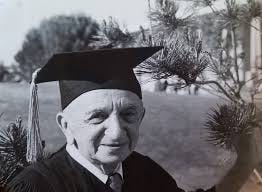

He spent the rest of his life in relative obscurity living in California. He never married and had minimal affiliation with the Jewish community. Only a handful of older Jews even knew his story. He changed his name to George Nagel.

During his time as George Nagel he became involved in real estate, but for the most part stayed under the radar. In his 80’s he enrolled in college to get an undergraduate degree in psychology. At the very end of his life, at the behest of his great-nephew, he decided to return to Israel and his town of Kfar Chassidim. He was still nervous that the community members resented him at best or, at worst, thought he was a criminal. It was why he had run away from that life in the first place.

He finally mustered up the courage to visit. He had no idea what to expect. And, as Rabbi Dunner movingly describes, when he finally returned to the his village he was greeted by throngs of his former Chassidim:

They arrived at the hall, which was packed with hundreds of people who had gathered to meet the man who had put Kfar Hasidim on the map. Old and young, religious and secular—everyone connected to the village was there. A seat at the front was left empty for George, and as a hush descended he slowly made his way toward his seat and sat down under the large welcome sign that adorned the front wall. An elderly man stood up and turned towards George.

“Rebbe, do you remember me?” he asked.

George looked at him, trying to figure out who he was.

“I’m not sure,” he said. “Are you Chaimke? Chaimke Geldfarb?”

Chaimke smiled. “Yes, Rebbe, it’s me.” His voice was hoarse with emotion. “On behalf of all the residents of our Kfar, I want to welcome you back home. You were probably nervous to come here. You probably think we are angry with you. You probably think that because you brought us here from Poland, away from our homes, away from our families, to build your dream, not ours. And then it all went wrong, so you think we are angry that it all went wrong. But Rebbe, if that’s what you think, you’re mistaken. Because Rebbe—you saved our lives—if it were not for you, we would all have been killed by the Nazis.”

“Look over there …” Chaimke pointed toward a group of people in the middle of the hall. “That’s my son with his wife and children, and next to him my two daughters with their husbands and children. My parents, uncles, aunts, brothers, sisters, and their children—all murdered by the Nazis. But we came with you, Rebbe. We built this place. We founded this village. We survived. And you were the one who saved our lives. And for that we thank you. Thank you for our lives, and for the lives of our children and grandchildren. We can never thank you enough.”

Chaimke sat down, and an old woman rose to speak.

“Rebbe, do you remember me?”

George looked carefully at her.

“Sheindel, is that you?”

“Sheindel, yes, but now they call me Shoshana.”

Sheindel had a lump in her throat as she spoke, and she struggled to get the words out. “Rebbe, Rebbe, where have you been for so many years? We missed you! We needed you! Without you we would all be dead, and we would not have had our beautiful lives in our beautiful Israel. Why did you leave? Everything turned out OK in the end. Look at us, look at how lucky we are. We escaped from the murderers and built our own homes in God’s promised land. You said we could do it, and we did it.”

Sheindel began weeping. Tears flowed down her cheeks, as her daughter next to her put an arm around her shoulder.

“Rebbe, come home,” Sheindel sobbed, “you’ve been gone for far too long. It’s time to come home.”

After 40 years of loneliness the Yabloner Rebbe had returned home.

I asked Rav Moshe Weinberger in our episode on the Yabloner Rebbe why he thought the Yabloner Rebbe’s story was so important. He had recently brought members of his shul to his gravesite. While visiting the burial plot of the Yabloner Rebbe, in Kfar Chassidim, Rav Moshe Weinberger spoke, as follow:

There’s that part of ourselves that’s real, that wants to do the right thing, and then you get side tracked. You get lost, and you feel that you let Hakadosh Baruch Hu down in your life, and that nobody cares for you, nobody wants you. When he came back, and this woman said, they start calling, “Rebbe, Rebbe,” and she said, “If not for you, we would have all been dead. We would have been killed in Poland.” Can you imagine all those years, he never thought of it like that? It’s so crazy. There’s so many good things that we do, and there’s so many positive changes that we make in helping our children and other people. But you never think of that. You always think of the bad stuff. So he saved so many people, he saved these families, and all the years he never thought of that. So all the years, he couldn’t think of coming back to Eretz Yisrael. He couldn’t think of putting on a pair of tefillin. He couldn’t put on a pair of tefillin. He couldn’t think of doing anything.

What I care about is the courage of the person to do that, to come back. I care so much about the heart-breaking escape from Yiddishkeit, that he ran away because he felt he was no good, which is happening to so many of our kids and so many of our adults. Even the ones that are still frum, you look at them davening. They’re running away. Why are they running away? It’s not because they don’t believe in the Ribono Shel Olam. You think for a second he stopped being a chassidishe rebbe? He was all the years that he was George Nichol, Nagel, he called himself Nichol, George Nichol in Los Angeles, a businessman, every single minute he was Reb Yechezkel Taub, the rebbe from Yablon.

When it dawned upon him. When that woman called out, that’s what struck me in that narrative that I read. I don’t know if it was on Yom Kippur or later, when she just screamed out, “Rebbe!” He’s looking at himself, like, “Me?”

Once she said that, “Rebbe,” and he looked at himself again as not being George Nichol, but as being Yechezkel Taub, an einekel from tzadikei elyon, I’m now going back to the chozer and beyond, from all those tzadikim he came from, and that he was a person that spent his whole life, the earlier part of his life in kedusha and tehara. A million mikvos, a million tefillos, a million blatt gemara, sefarim hakedoshim, chassidim.

Then all of a sudden, he came back. From whatever madrega he came back, but he came back. So I think that we owe him, to come here to say thank you. Because this story to me is more inspiring than all of the stories I read about, the ones that never, ever had any detours.

And it is this perspective that I think highlights the connection between לא בשמים היא, it is not in heaven, and its meaning in the context of both Torah and Tefillah.

When we say the Torah is not in Heaven we mean that it is upon the interpretive community of the Jewish People to discover and determine the meaning of our Torah. It gives the Jewish People agency to create interpretive meaning. We don’t look towards God or even prophets to interpret and apply the laws of the Torah, the meaning rests in the hands of the Jewish People.

And in a similar way, this is exactly what underlies the concept of teshuva. Real teshuva, a return to who we really are, is itself an act of interpretation. Instead of interpreting a verse of the Torah or a line in the mishnah, Teshuva invites us into the world of self-interpretation. We are the text, so to speak, and we have the agency to find meaning and purpose in the narrative of our life. Teshuva is the act of interpretation that allows us to discover the true meaning of our very self.

I once heard in the name of Rav Moshe Shapiro that very often we tell ourselves that we would be able to do teshuva if only we were in a certain place. If only I was back in yeshiva. If only my parents were more supportive. If only my friends were more serious. To each of these “if only’s” we answer “לא בשמים היא,” it is not of there—שמים meaning not “heaven” but a plural for the word שם, meaning there. Teshuva is not in any of the “theres” in our lives. We hold the capacity and the agency to find the interpretive meaning in our lives to uncover our immutable connection to God.

Teshuvah is always close, it is always here, because it is always about us. It is always about transforming and sweetening us. Teshuvah is not a confrontation with an ominous alterity, it is the embrace of an idealized self. We are the monster at the end of the machzor.

Shabbos Reads — Books/Articles Mentioned

The Monster at the End of the Machzor, Dovid Bashevkin

The Amazing Return of the Yabloner Rebbe, Pini Dunner

The Amazing Return of the Yabloner Rebbe (Rabbi Dunner’s website), Pinni Dunner

The Rebbe of Change, 18forty Podcast

Check out All Parsha, where you can find weekly audio of Reading Jewish History in the Parsha, as well as other incredible presenters and amazing features that will enhance your Parsha journey!

Reading Jewish History in the Parsha has been generously sponsored by my dearest friends Janet and Lior Hod and family with immense gratitude to Hashem.

Wow, beautiful article

Thank you

This was wonderful, thank you!!!!!