The accompanying shiur is available on the Orthodox Union's parsha learning app: All Parsha.

Sefer Bereishis finally comes to its conclusion.

In the final chapter of the story, Yaakov gathers all of his children and tells them that he intends to reveal the end of the story. Not just the end of their story but the collective story of the Jewish people. Yaakov was going to reveal, as Rashi explains, when Mashiach will come.

And then suddenly he stops. Instead, he gives each child a blessing.

This closing chapter is bizarre.

First, why did Yaakov want to reveal the end of story? What was he intending to accomplish?

And why did he suddenly stop?

Last, why did Yaakov instead give each child a blessing?

Rashi explains that Yaakov lost his vision of the end of days and instead just decided to talk about other things.

Really?!

Was this like a tense Shabbos meal where someone brings up a sensitive subject and then Mom pipes in and says, “Why don’t we talk about something more pleasant?”

Yaakov’s original plan to reveal the End of Days seems strange and his Plan B seems even stranger. Ok, I can’t tell you about the messianic age, but enjoy your consolation prize, a blessing.

How should we understand this sequence of events?

To understand all of this, let’s explore one of the most exciting chapters in Jewish history: the attempt to find the lost tribes.

My friend Nachi Weinstein, host of the Seforim Chatter podcast, is actually rolling out an incredible series on the lost tribes now. His guidance on this subject as well as his book recommendations were invaluable for this exploration. If you haven’t already, be sure to check out his podcast, particularly his incredible series on the lost tribes! His treatment of Jewish history is always eye-opening!

The last we hear about the Ten Tribes is in the 17th chapter of the second book of Melachim. Following the split of the Jewish Kingdom, the Assyrian Empire attacks the Jewish people and exiles the Israelite Kingdom, leaving the Kingdom of Yehuda intact. There is much speculation about which precise tribes were the ones actually exiled and even how many were exiled—it’s not clear in Tanakh—but by the time of the Mishnah it is taken as a given that ten tribes were lost.

While the Mishnah records a dispute about whether we should ever even expect the lost tribes to return, that very possibility has been wrapped up with messianic expectations. As Zvi Ben-Dor Benite writes in his book, The Ten Lost Tribes: A World History, the most comprehensive treatment of the subject:

As we have seen, the ten tribes belong in the messianic package; all the prophets lump their return together with the other signs of the end of time. If the central question about the ten lost tribes has long been: where are they? then the central question concerning the messianic age is: when will it happen? An untold number of thinkers have undertaken to answer that question.

The search for the lost tribes, infused with messianic expectations, has brought Indiana Jones-like characters out of the woodwork both from within and outside the Jewish community. Maharal, in a remarkable passage in his work Netzach Yisroel, warns people not to despair from the increasingly detailed cartography that emerged in his generation. Even if we map out much of the world, there are still places, Maharal explains, that are unknown to civilization where the lost tribes may still reside.

One of the earliest and most fabulous tales about the lost tribes is the story of Eldad Hadani. In 883 CE, a mysterious traveler named Eldad HaDani arrived at the Jewish community in North Africa claiming to be from the lost tribe of Dan. He shared harrowing stories—escaping cannibals, being sold into slavery—but most importantly claimed that the lost tribes remain intact. Beyond the Sambation River, the lost tribes still rule themselves with a powerful army and a glorious civilization. The only way, Eldad explains, to communicate with the other tribes living beyond the river is with carrier pigeons. It’s hard to ignore the resemblance to Wakanda, the fictional city in Marvel’s Black Panther. Eldad’s tales circulated and more recently have been translated into English with a commentary by Micha J. Perry in his book Eldad’s Travels: A Journey from the Lost Tribes to the Present.

The question as to the veracity of Eldad’s claims was sent before Rav Tzemach Gaon who responded positively to Eldad’s claims. This became the first in a line of major rabbinic questions evaluating the halachic possibility that those claiming to be from the lost tribes, even isolated for centuries, should still retain their Jewish identity. The most notable and exhaustive rabbinic treatment of this question is from Rav Dovid ben Zimra, known as the Radbaz, who wrote a responsa regarding the halachic status of a child born to a woman claiming descent from the lost tribes. This responsa was central to the modern day halachic debate of accepting Ethiopian Jews into the State of Israel through the Law of Return. Many of these responsa rely on the reports of Eldad HaDani as factual—the lost tribes still exist and can, in fact, return.

Perhaps one of the most remarkable stories involving the search for the lost tribes was led by Menashe ben Israel, one of the most incredible figures in Jewish history. Menashe ben Israel lived for a period in the same neighborhood as Rembrandt and may have advised Rembrandt on some of his artistic depictions of the Bible. Some even assume one of Rembrandt's small rabbinic etchings is of Menashe ben Israel.

In 1644, Antonio Montezinos, also called Aaron Levi arrived in Amsterdam with a report that he had found the lost tribes. During his time wandering as a Portuguese converso, he stumbled upon an Indian tribe in South America. He was convinced they were from the lost tribes. They recited Shema and claimed their forefathers were Avraham, Yitzchak, and Yaakov. After arriving in Amsterdam his story soon came before Menashe ben Israel.

This was not an exclusively Jewish fascination. John Dury, a Calvinist minister also heard about Montezinos’s story. He became convinced that the American Indians were from the lost tribes—an idea that fueled his Christian hopes that the reemergence of the lost tribes might usher in the End of Days. More and more Christian millenarians, those convinced the End of Days was near, began reaching out to Menashe ben Israel in the hopes he could either confirm the existence of the lost tribes or, at the very least, investigate these reports.

Initially, Menashe, while intrigued, was not convinced. But Rabbi Menashe ben Israel returned to the prophecies of Daniel and began to wonder if, in fact, his Christian friends were perhaps on to something. “When He shall have accomplished to scatter the power of the holy people,” the 12th chapter of Daniel writes, “all these things shall be finished.” Perhaps, Menashe ben Israel reasoned, the way to bring the Messianic age is to have Jews scattered in each corner of the world. With the discovery of alleged Jews in the Americas, maybe the time of Messiah has finally arrived.

There was, however, one problem.

Even if the Indians were, in fact, lost tribes, there was still one place that did not have Jews: England.

Jews were expelled from England in 1290 under the orders of Edward I. It seemed like redemption was so close—Jews were scattered everywhere—if only they would be allowed readmission to England.

Rabbi Menashe ben Israel published his work Mikveh Yisroel in 1650. It was an outgrowth of his correspondence with Christian millenarians. It was published in 3 languages—Spanish, Latin, and English—in the hopes that its contents would persuade the widest audience possible of the messianic potential of locating all of the lost tribes and having Jews throughout the world.

Mikveh Yisroel opens with a dedication addressed specifically to the English parliament. But a book alone would not be enough to persuade a country to readmit Jews centuries after they were expelled. Instead, Menashe decided to travel to England in the hopes of prevailing upon parliament. He departed to England in September of 1655.

The English people were not as enthusiastic about the readmission of the Jewish people. In the translator’s preface to the English edition of Mikveh Yisroel, the translator, Moses Wall, writes that his goal was to “remove our sinful hatred from off that people.”

Oliver Cromwell, then Lord Protector of England, was not dismissive of Menashe ben Israel. Menashe was careful to make the case for the return of the Jewish people to Israel primarily for utilitarian reasons—specifically the potential boon Jews could offer the economy. Cromwell was in favor of the Jewish return to England but when the vote was brought before the government body for debate, in what is known as the Whitehall Conference, they emerged without a clear recommendation.

Menashe ben Israel was crestfallen. It seemed his mission to England had failed. His disappointment turned to mourning when his son Samuel, who accompanied him to London, died in September of 1657. He left England a broken man. Menashe ben Israel died just a month later, after returning from England, on November 20. 1657.

Menashe’s efforts, however, were not a complete failure. Charles II, who after losing a battle to Cromwell in 1651 had been in exile, finally returned and assumed the throne in 1660. Cromwell had passed away two years earlier, but Charles II ordered that his remains be exhumed and his head was mounted on a spike outside of Westminster Hall for the next 25 years. But the small Jewish community that surfaced during the time of Menashe ben Israel’s efforts remained and Charles II allowed them to stay. They brought one of Menashe ben Israel’s former colleagues, Rabbi Yaakov Sasportas, to lead the community. Rabbi Sasportas just a few years later would lead the battle against Shabbetai Tzvi.

Menashe ben Israel’s efforts to bring redemption would ultimately provide a platform for Rabbi Yaakov Sasportas to ensure the false messianic hopes of Shabtai Tzvi would never be realized.

Yaakov gathers his children, the twelve tribes. He will reveal to them the end of days.

What was he hoping to accomplish?

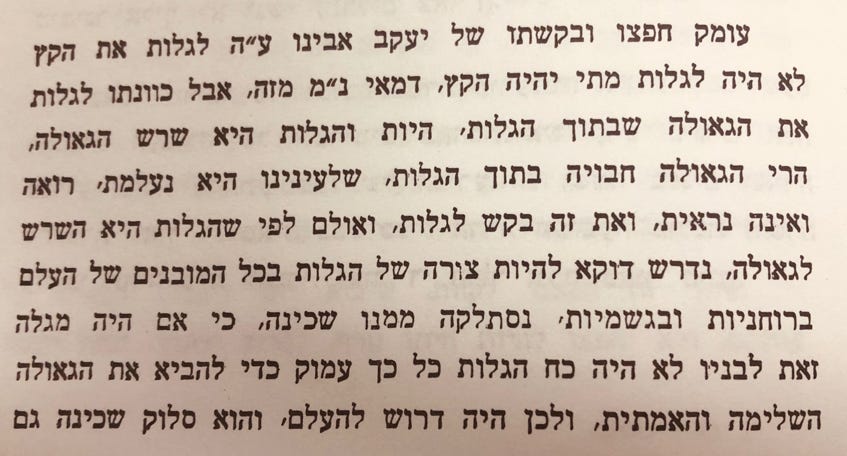

Rav Yaakov Moshe Charlop suggests something incredible.

Yaakov was not trying to reveal a date—what day will Mashiach come—rather he wanted to give his children the ability to discover redemption even amidst exile. Yaakov wanted his children to remain connected to redemption even while they were displaced in exile.

But exile and redemption are intertwined—if they knew too much about redemption, exile would lose its redemptive power.

So God prevented him from revealing the end.

As the Sefas Emes explains, in a teaching that poetically like Yaakov’s revelation stops in the middle, Yaakov wanted to reveal the end to make the middle—the experience in exile—easier. He wanted to help his children see redemption even in exile.

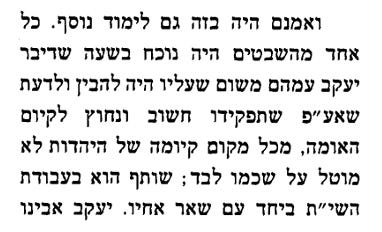

After Yaakov loses the ability to transmit his redemptive vision he does something else. The closest thing to actual redemption: he gives his children blessings.

This, Rav Yaakov Kaminetsky explains, provides a glimpse of redemption. Yaakov doesn’t just give each child a private blessing—he blesses each child in front of the rest to ensure that each child hears one another’s blessing. Yaakov wanted to impress on each of the tribes that every individual has their own strength and blessing, and each of your blessings differs from one another. More important than the blessing each child received, was the knowledge that each child learned that every child has a different blessing.

And that is a redemptive capacity—seeing the unique purpose and strength of all those around you. Each tribe, its own ability. Each tribe, finally found.

Shabbos Reads — Books/Articles Mentioned

Eldad’s Travels: A Journey from the Lost Tribes to the Present, Micha J. Perry

The Ten Lost Tribes: A World History, Zvi Ben-Dor Benite

Rembrandt’s Jews, Steven Nadler

Menasseh ben Israel: Rabbi of Amsterdam, Steven Nadler

The Hope of Israel, Menasseh ben Israel (eds. Henry Mechoulan and Gerard Nahon)

Check out All Parsha, where you can find weekly audio of Reading Jewish History in the Parsha, as well as other incredible presenters and amazing features that will enhance your Parsha journey!

Was England really the only place without Jews at that time? How did Menashe ben Israel think the coming of the Messiah was dependant on a British Jewish population?