The accompanying shiur is available on the Orthodox Union's parsha learning app: All Parsha.

Most people have heard of the Five Books of Moses, but have you ever heard of the Seven Books of Moses?

In our parsha, there are two verses that we recite each time we remove the Torah from the Aaron Kodesh. The Talmud considers these verses to be their own independent book of the Torah. They are the words:

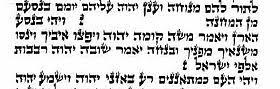

וַיְהִי בִּנְסֹעַ הָאָרֹן וַיֹּאמֶר מֹשֶׁה קוּמָה יְהֹוָה וְיָפֻצוּ אֹיְבֶיךָ וְיָנֻסוּ מְשַׂנְאֶיךָ מִפָּנֶיךָ׃

וּבְנֻחֹה יֹאמַר שׁוּבָה יְהֹוָה רִבְבוֹת אַלְפֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל׃

The Talmud explains that these two verses are considered their own book of the Torah. This means that there are really seven books of the Torah: Bereishis, Shemos, Vayikra, Bamidbar up until these verses, the verses of ויהי בנסוע הארון, the verses in the book of Bamidbar that follow these verses and the book of Devarim. These two verses essentially divide the book of Bamidbar into three separate books.

There is clearly something unique about these two verses. You may notice that inside the Sefer Torah, these two verses are bracketed by the letter nun.

What makes these verses so special? Why are they considered to be their own book in the Torah?

One opinion in the Talmud explains that these verses are actually written out of place. They should have been written elsewhere, but they were included here to break up the negative stories of the Jewish People leaving Sinai and then later complaining to God. It’s a strange reason to include verses out of place. Were the rabbis worried that readers of the Torah would become too sad if they read these stories back to back? Why exactly are the verses of ויהי בנסוע included here?

Rav Yaakov ben Asher, in his commentary Baal HaTurim, suggests an allusion to these two verses comprising their own book of the Torah. He explains that the verse ויהי בנסוע has 12 words corresponding to the last verse in the Torah which also has 12 words. And the second verse ובנחה יאמר has 7 words, the same number as the first verse in the Torah.

It is a clever allusion. Just like the verses in our parsha have seven and 12 words, so too the Torah itself begins with a verse that has seven words and ends with a verse that has 12 words—so we see the verses of ויהי בנסע are like their own book of the Torah.

There’s one obvious problem.

As Rav Tzadok points out, the allusion is backwards. The first verse in the Torah (בראשית ברא) has seven words and the last verse in the Torah has 12 words—so shouldn’t the first verse of ויהי בנסע have seven words and the verse of ובנחה יאמר have 12? As Rav Tzadok writes:

ויש להבין לפי רמז זה למה נרמז קודם נגד הפסוק דסוף התורה מספר י"ב ואחר כך מספר ז' תיבות כנגד הפסוק דתחלת התורה. ובתורה להיפך מתחיל בפסוק שיש בו ז' תיבות ומסיים בפ' שיש בו י"ב תיבות.

Why does the first verse, ויהי בנסוע, correspond to the last verse of the Torah, and the second verse, ובנחה יאמר, correspond to the first verse in the Torah? Isn’t it backwards?

To understand the meaning of this backwards allusion and the larger significance of the verses of ויהי בנסע in the Torah, let’s explore the notion of alternative history and its connection to Torah.

Most people encounter the concept of Alternative History not through studying Jewish history, but through their obsession with sports. Alternative History explores how the world might have been different if historical events had unfolded differently. It's a common parlor game among sports fans.

Bill Simmon’s The Book of Basketball dedicates an entire chapter to such questions, which he calls “The What-If Game.” Seasoned sports fans already know the most famous what-if question: What if the Portland Trail Blazers selected Michael Jordan with their pick in the 1984 NBA draft instead of Sam Bowie? Sports history is filled with such questions. What if Wayne Gretzky had never been traded to the Kings? What if Lebron James decided to play soccer as a kid instead of basketball? Sports Illustrated had a full issue exploring the greatest “what-ifs” of sports—they even designed mock “what-if” magazine covers imagining how they would have covered such events had they turned out differently.

The appeal of such “what-if” questions extends beyond sports. As Bill Simmons explains:

We spend an inordinate amount of time playing the what-if game. What if I never got married? What if I had gone to Harvard instead of Yale? What if I hadn’t punched my boss in the face?…You can’t go back, and you know you can’t go back, but you keep rehashing it anyway.

This of course is not a recent phenomenon. People have been reimagining draft orders or picturing their favorite shows or movies with different lead actors for as long as we've had imaginations. Imagine if Dwight Schrute of The Office was played by Seth Rogan who auditioned for the role instead of Rainn Wilson who, as we know, secured the role. Most of the time, however, such what-if speculation was reserved for more serious historical questions.

Renowned alternative historian, Harry Turteldove, writes in his book The Best Alternate History Stories of the 20th Century that the first example of Alternate History dates back two millennia when Roman historian Titus Livius, often referred to as Livy, speculated what would have happened if Alexander the Great had succeeded in conquering Europe.

Jewish tradition does not dismiss the importance of such questions either. The Ohr HaChaim suggests, based on the Talmud in Sotah 9a, that had Moshe entered the land of Israel and built the Beis HaMikdash it could never have been destroyed. Instead, had the Jewish People sinned, God would have taken His wrath out on the Jewish People instead of destroying the Beis Hamikdash. Moshe, of course, did not enter the Land of Israel but such speculation of what would have happened had he entered is certainly a form of Alternative History.

Alternative History is sometimes quite bleak.

In 1976, Tradition Journal published an article by Gary Epstein, entitled “Could Judaism Survive Israel?” It is one of the few Tradition articles that was published with an introductory editorial note that stated, “Although the Editors of TRADITION regard the State of Israel as a pivotal instrumentality for the survival of Judaism in the modern world, they deem it important to open the pages of this journal for the discussion of controversial opinions.” This editorial warning was not enough to help the article skirt controversy. The article, which considers the future of Judaism if, God forbid, Israel was destroyed, provoked a storm of letters to the editor questioning the merit of publishing such speculation. “A more tasteless article than the one by Gary Epstein on his self-serving proposition that Judaism can survive the fall of Israel I have not read in a long time,” one letter to the editor read. Another letter paraphrased the famous line of the Kotzker Rebbe, “Much of this article should not have been thought about, more of it not spoken about, and most of it not put into printed form.” The purpose of Alternative History was clearly lost on many of the readers.

Of course, not all Alternative Jewish History is so bleak. Professor Jeffery Gurock uses Alternative History in his book, The Holocaust Averted: An Alternate History of American Jewry, 1938-1967, to shed light on his normal focus: actual American Jewish History. This is an important function of Alternative History—helping us better understand and appreciate the nature of our actual history. As Gurock explains:

How does this presumed saga help us understand and appreciate the real course of the postwar years for American Jews? Overlaying this dystopian counterfactual vision resides a series of provocative messages about the community’s actual history and ultimately its destiny. Through our foggy mirror of fiction, the legacy of real events is visible.

Others have followed in Gurock’s footsteps and used Alternative History to explore the actual history of the American Jewish Community. Professor Zev Eleff considered the Alternative History of a far more niche question: What if Rav Aharon Lichtenstein never made aliya and instead remained in the United States? Eleff explores how Rav Lichtenstein’s presence could have potentially impacted the selection process for the next president of Yeshiva University—perhaps Rabbi Emanuel Rackman would have been selected as YU President instead of Rabbi Lamm. Even when considering niche questions, Alternative History is still a precarious game to play. Eleff’s article provoked a response from Dr. Tovah Lichtenstein, Rav Lichtenstein’s wife, who criticized Eleff’s imagined history for assigning far too passive a role to Rav Lichtenstein had he stayed. In response, Zev Eleff published an article, cleverly entitled, “Retiring my Modern Orthodox DeLorean,” a reference to the famed car from the movie Back to the Future, that essentially concluded his career as an alternative historian. Eleff begins his response article with an apology for the potential insensitivity that Alternative History endeavors:

For most of us, Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein was a teacher and heroic symbol. That’s what has made the “What if Rav Aharon had Stayed” conversation so very interesting. Still, for others he was a husband, father and grandfather. Changing his life, retaining him for American Jewry, however fictitious, must have erased memories and milestones. I am sorry if the project appeared insensitive.

Despite the brevity of his career as an alternative historian, Professor Eleff’s retirement should not be seen as the end of Alternative History within the Modern Orthodox community. Many others have engaged in the practice as well. Just a month before Eleff’s article on Alternative History Leah Sarna published an article that explored a different provocative question: What if Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik had been a woman? The article, written in response to the Orthodox Union’s statement on Women’s Leadership, imagines an alternative universe where “Josefa Beila Soloveitchik would have studied Tanakh growing up, but she would not have been tutored in the complex methodologies of Brisk.” Similar to past examples of Alternative History, Sarna justified her speculation as a window to better understand the present moment. She writes:

Unfortunately, this is not some dystopian novel. This happens in every generation, including our own. Women of brilliance in mind and spirit are born into the Orthodox community, and our community actively deprives itself of their service—not because of their brains or potential, but their gender.

Good Alternative History will always help illuminate the actual course of history. As Gavriel Rosenfeld writes in his introduction to the book, What Ifs of Jewish History: From Abraham to Zionism, “Scholars employ counterfactual reasoning to better understand the forces of historical causality.” Anytime someone (other than Norm Macdonald) speculates about going in a time machine to kill baby Hitler they are really making a claim about the causes of the atrocities of the Holocaust—if Hitler was killed as a baby perhaps it could have been avoided, in whole or in part. “Whenever we make the causal claim that ‘x caused y,’” Rosenfeld writes, “we implicitly affirm that “y would not have occurred in the absence of x.”

Still, there is another reason—beyond historical causality—that we engage in Alternative History. And here Rosenfeld shares something truly illuminating:

The third and perhaps primary reason why we ask “what if?” lies in the broader area of human psychology. It is in our very nature as human beings to wonder “what if?” At various junctures in our lives, we may speculate about what might have happened if certain events had or had not occurred in our past: what if we had lived in a different place, attended a different school, taken a different job, married a different spouse? When we ask such questions, we are really expressing our feelings about the present. We are either grateful that things worked out as they did, or we regret that they did not occur differently. The same concerns are involved in the realm of counterfactual history. Counterfactual history explores the past less for its own sake than to utilize it instrumentally to comment upon the state of the contemporary world. When producers of counterfactual histories imagine how the past might have been different, they invariably express their own subjective hopes and fears.

And this brings us back to the verses of ויהי בנסע הארון.

Rav Soloveitchik has a truly remarkable thesis about the significance of these verses: They represent the alternative history of the Jewish People.

These verses appear just as the Jewish People are leaving their encampment at Mount Sinai. Once they leave their location at the site of Revelation, the Jewish People begin to unravel. They start complaining about the conditions of their journey to the Land of Israel. Jewish history itself begins to unravel following the departure of the Jewish people from Sinai—the sin of the spies, wandering for 40 years, and Moshe being condemned to never enter into the land of Israel.

The verses of ויהי בנסע dare to imagine an alternative history where the Jewish People travel directly from Mount Sinai into the Land of Israel. An alternative history where Moshe leads the Jewish People into the land of Israel.

As Rabbi Soloveitchik writes regarding that alternative version of Biblical history:

There would have been no need for an inverted nun at the beginning and inverted nun at the end. The verse would have been the climax of the whole story, not an inversion. Jewish history would have taken a different course. Had Moses entered the Land of Israel, our history would never have been taken from us. The messianic era would have commenced with the conquest of the Land of Israel by Moses.

But it was not to be. Once leaving Sinai, the Jewish People started to fall apart and the possibility of Moshe leading them directly into the Land of Israel was bracketed into the world of Alternative History. Rav Soloveitchik explains:

It was then that Vayehi bi-neso’a ha-aron lost its place. Instead of the march bringing them closer to the Land of Israel, it took them away from the Promised Land. The nuns were inverted, and with the inversion Jewish history became inverted—and it is still inverted. The parshah is still dislocated.

Despite the dislocation, these verses were still canonized. Everyone has an alternative history that hovers in the background of their minds. Every decision we make—who to marry, where to live, what profession to pursue—creates the alternative universe that asks “What if life had worked out differently?”

And this is why the allusion of the Baal haTurim is so profound—the verse of ויהי בנסע corresponds to the last verse in the Torah, while the second verse ובנחה יאמר corresponds to the first verse in the Torah. It is a prayer of sorts that our endings—how our lives actually unfold—should embody the same passion, idealism, and intentionality as our beginnings. Alternative history begins, where real life ends. And when we take the Torah from the Ark, we silently pray that however our life may have unfolded, wherever it may have ended, whatever moment we have before us, should have the same optimistic sentiment as our beginnings. Where Alternative History ends, real life begins: where we end up becomes a new beginning.

Shabbos Reads — Books/Articles Mentioned

The Book of Basketball: The NBA According to the Sports Guy, Bill Simmons

The Best Alternate History Stories of the 20th Century, Harry Turteldove

Could Judaism Survive Israel? Gary Epstein

The Holocaust Averted: An Alternate History of American Jewry, 1938-1967, Jeffery Gurock

What if Rav Aharon had Stayed? A Counter-History of Postwar Orthodox Judaism in the United States, Zev Eleff

Countering Counter-History: Re-Considering Rav Aharon’s Road Not Taken, Tovah Lichenstein

Retiring My Modern Orthodox DeLorean, Zev Eleff

An Alternative History of American Modern Orthodoxy, Leah Sarna

What Ifs of Jewish History: From Abraham to Zionism, Gavriel D. Rosenfeld

Vision and Leadership: Reflections on Joseph and Moses, Joseph B. Soloveitchik

Check out All Parsha, where you can find weekly audio of Reading Jewish History in the Parsha, as well as other incredible presenters and amazing features that will enhance your Parsha journey!

Reading Jewish History in the Parsha has been generously sponsored by my dearest friends Janet and Lior Hod and family with immense gratitude to Hashem.

https://misfittorah.substack.com/p/devar-torah-vayakhel-pekudei-chaos

This was an attempt at the kind of thing you're describing