The accompanying shiur is available on the Orthodox Union's parsha learning app: All Parsha.

The first rabbi I ever met was my grandfather, Rabbi Moshe Bekritsky. At a time when few sent their children to study in Yeshiva, my grandfather insisted on it. He was originally a student in Yeshiva Torah V’Daas, where he studied with Reb Shraga Feivel Mendelowitz. Even though Reb Shraga Feivel completed rabbinic ordination he insisted that his students call him Mr. Mendelowitz, which my grandfather dutifully did his entire life. When Rav Dovid Leibowitz established his yeshiva, named after his great-uncle Rav Yisroel Meir Kagen, the Chofetz Chaim, my grandfather joined him. My grandfather formally became a rabbi at the first chag hasemicha, rabbinic ordination celebration, of the newly established Yeshivas Chofetz Chaim.

In the sole existing picture of the ceremony, Rav Dovid Leibowitz is seated next to the then-mashgiach of the yeshiva, Rav Chaim Pinchas Scheinberg, who was then still in his mustache era before becoming instantly recognizable for wearing many many pairs of tzitzis, a custom he adopted much later in life.

Most importantly, at the first chag hasemicha of Yeshivas Chofetz Chaim, they wore tuxedos, a tradition I would urge Yeshivas to consider bringing back.

Nowadays, particularly in the United States, getting the title “Rabbi” is a lot easier. Many incredible rabbis I know have not completed rabbinic ordination. It doesn’t take all that much to be called “Rabbi.” Still, my mother insisted I formally complete semicha before using the title—my grandfather worked hard for it, and so should I.

But what exactly is semicha and where did the tradition of semicha begin?

The story happens to begin in our parsha, Pinchas.

After detailing the laws of inheritance, Moshe turns to God and asks, who will inherit his leadership? The Jewish People, Moshe says, should not be left like a flock without a shepherd.

Take your hand, God instructs Moshe, and place it upon Yehoshua bin Nun in front of Elazar the Kohen and the entire Jewish People. And then God tells Moshe:

וְנָתַתָּה מֵהוֹדְךָ עָלָיו לְמַעַן יִשְׁמְעוּ כׇּל־עֲדַת בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל׃

Invest him with some of your authority, so that the whole Israelite community may obey.

Moshe does everything God instructs.

Well, sort of. God told Moshe to rest one hand on Yehoshua, and Moshe rested both of his hands.

What is the point of Moshe resting either hand on Yehoshua? And what exactly does Hashem mean when he tells Moshe, וְנָתַתָּה מֵהוֹדְךָ עָלָיו, invest some of your authority upon Yehoshua?

Rambam writes that Moshe resting his hands upon Yehoshua became the basis for all future semicha, rabbinic ordination.

So to truly understand the meaning of semicha, let’s explore the history of rabbinic ordination.

Yehoshua was the first ordained rabbi. The Talmud derives all future ordinations from the first rabbinic ordination of Moshe to Yehoshua. Still, the Talmud acknowledges, that future ordinations do not actually require placing hands upon the student, as Moshe did to Yehoshua.

For generations, rabbinic ordination came with significant authority. Only rabbis with formal semicha could serve on a Beis Din for capital punishment, impose fines, sanctify the calendar, and, at least according to Tosafos, serve on a Beis Din for conversion.

So when did this original semicha stop?

A few decades after the destruction of the Temple, as the Roman government continued its persecution of the Jewish People, they made a concerted effort to end formal rabbinic ordination, and they were almost successful. Almost. Yehuda ben Bava, the Talmud recounts, ensured the continuation of ordination by formally ordaining five of his students. Shortly afterward, Yehuda ben Bava urged his students to run for their lives—now that they were ordained they would be subject to additional persecution from the Romans. Yehuda ben Bava, too elderly to flee, was murdered by the Romans. The institution of semicha, however, lived to see another day.

Most scholars assume that semicha continued for nearly two more centuries, until Hillel II’s institution of the fixed calendar around 360 CE. Some, however, have suggested that semicha continued into the first millennium.

Undoubtedly, the semicha we have today differs from the certification mentioned in the Talmud. Originally, semicha represented someone who possessed an unbroken tradition that dates back to Yehoshua—eventually, semicha became more like a doctoral degree—indicating that a student has now entered the class of scholars.

Even after semicha’s representative status changed it remained an important tool of authority. As Jacob Katz explains in his fascinating article, “Rabbinical Authority and Authorization in the Middle Ages,” in 921 CE Rav Saadia Gaon, who lived in Babylonia, questioned the Jewish calendar calculations of Aaron Ben Meir, a scholar who lived in Jerusalem. Their debate soon revolved around the question of who possessed the actual authentic authority to definitively institute the Jewish calendar. Ben Meir wanted to “recover the authority previously held by the institutions of the Holy Land.” Rav Saadia Gaon, on the other hand, felt such authority had ceased once the formal chain of semicha disappeared. Instead, Rav Saadia Gaon understood that the calendar conundrum should be solved based on scholarly authority, which he argued he possessed far more than his counterpart in the Land of Israel. Here, the role of semicha sees its first change—from a certification of an unbroken tradition to a testimony of one’s scholarly acumen. As Katz explains:

The problem of religious authority shifted considerably when, in the wake of political events and processes, the centers of Jewish communal life shifted to the Mediterranean countries—North Africa, Italy, Spain and even France and Germany. The scholars of those countries could not base their authority on either a chain of personal linkage or the continuity of their institutions. The Semikah as the means of legitimation of authority based on Talmudic tradition nonetheless played a certain role.

Renewing Semicha

Semicha originally began as an exclusive institution for rabbinic leadership in the Land of Israel. Rambam writes that semicha must be given in the Land of Israel because, as Rav Soloveitchik later explained, semicha requires the consent of the entirety of the Jewish People, and it is only in the Land of Israel that the Jewish People have such a status.

For likely 500 years already, semicha as an authoritative link to tradition had disappeared. Rambam, however, speculates that there may be a mechanism to reintroduce formal semicha. Rambam writes:

נִרְאִין לִי הַדְּבָרִים שֶׁאִם הִסְכִּימוּ כָּל הַחֲכָמִים שֶׁבְּאֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל לְמַנּוֹת דַּיָּנִים וְלִסְמֹךְ אוֹתָם הֲרֵי אֵלּוּ סְמוּכִים וְיֵשׁ לָהֶן לָדוּן דִּינֵי קְנָסוֹת וְיֵשׁ לָהֶן לִסְמֹךְ לַאֲחֵרִים. אִם כֵּן לָמָּה הָיוּ הַחֲכָמִים מִצְטַעֲרִין עַל הַסְּמִיכָה כְּדֵי שֶׁלֹּא יִבָּטְלוּ דִּינֵי קְנָסוֹת מִיִּשְׂרָאֵל. לְפִי שֶׁיִּשְׂרָאֵל מְפֻזָּרִין וְאִי אֶפְשָׁר שֶׁיַּסְכִּימוּ כֻּלָּן. וְאִם הָיָה שָׁם סָמוּךְ מִפִּי סָמוּךְ אֵינוֹ צָרִיךְ דַּעַת כֻּלָּן אֶלָּא דָּן דִּינֵי קְנָסוֹת לַכּל שֶׁהֲרֵי נִסְמַךְ מִפִּי בֵּית דִּין. וְהַדָּבָר צָרִיךְ הֶכְרֵעַ:

It appears to me that if all the all the wise men in Eretz Yisrael agree to appoint judges and convey semichah upon them, the semichah is binding and these judges may adjudicate cases involving financial penalties and convey semichah upon others.

If so, why did the Sages suffer anguish over the institution of semichah, so that the judgment of cases involving financial penalties would not be nullified among the Jewish people? Because the Jewish people were dispersed, and it is impossible that all could agree. If, by contrast, there was a person who had received semichah from a person who had received semichah, he does not require the consent of all others. Instead, he may adjudicate cases involving financial penalties for everyone, for he received semichah from a court. The question whether semichah can be renewed requires resolution.

Rambam suggests that semicha could be renewed if all of the sages in the Land of Israel gather together and mutually agree on reinstituting semicha. He concludes, however, that this matter still requires further consideration. Notably, Rav Dov Revel, the first president of Yeshiva University, questions whether the Rambam himself even wrote those concluding words.

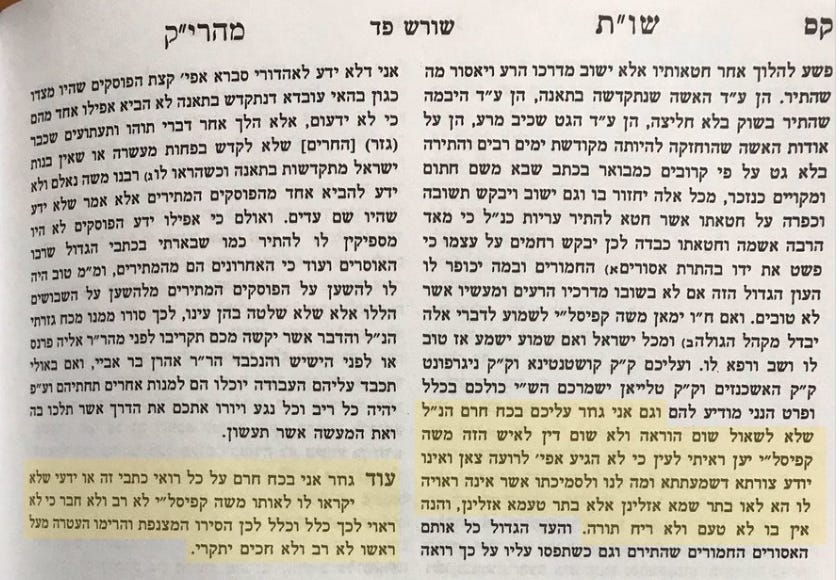

The potential innovation of the Rambam gave rise to several efforts throughout Jewish history to renew formal semicha. Most famous of all was the effort made in 1538 by Yaakov Beirav, known as Mahari Beirav, who assembled 25 leading rabbis of the holy city of Tzfat and conferred semicha upon, among others, Rav Yosef Karo, author of the Shulchan Aruch.

Why did Mahari Beirav want to reinstitute semicha?

Professor Jacob Katz, in his definitive and detailed article on the subject, “The Dispute between Jacob Berab and Lev ben Habib over Renewing Ordination,” rejects insinuations by earlier historians that he was motivated by some personal competitiveness to demonstrate the authority of the rabbinate in Tzfat over Jerusalem. Instead, Katz sees this initiative as deeply Messianic. Still reeling over the Spanish Expulsion in 1492, as well as the unfulfilled Messianic expectations heralded by Shlomo Molcho, there was widespread speculation that the End of Days was near. Mahari Beirav, who himself was exiled from Spain, hoped the renewal of semicha would be the first step in realizing those Messianic dreams. As Katz writes, “Ordination renewal is not a righteous act by virtue of which one gains Redemption, but constitutes the first stage in the process of Redemption.”

Some scholars have suggested that through the renewal of ordination, a better means of providing repentance would be made available for the anusim, sometimes called Marranos, who were forcibly converted to Christianity under Spanish rule. Anusim would be able to receive formal punishment in Beit Din, something only capable of being administered by those with semicha, thereby providing a higher form of repentance and ushering in the Messianic age.

Students of Jewish history surely know that one does not make rabbinic friends easily while trying to hasten the Messiah. The initiative of Mahari Beirav was fiercely opposed by Rav Levi ibn Chaviv, known by the acronym Maharalbach. As a child, Maharalbach was forcibly baptized before eventually emigrating to the Holy Land and assuming a position as a Rav in Jerusalem. He was much more suspicious of any attempts to proactively usher in redemption and declared that the reinstitution of semicha did not have any validity. Along with the agreement of R. Dovid ben Zimra, known as the Ridvaz, they successfully prevented the efforts to revive semicha from gaining any mainstream acceptance. Mahari Beirav, somewhat embarrassed by the controversy, did not attempt to give anyone rabbinic ordination again.

Interestingly, Rav Yosef Karo never explicitly discusses this incident in any of his works. Apart from a reference in his Maggid Meisharim, his mystical diary, predicting that he would one day be ordained, this incident is never discussed. Apparently, Rav Yosef Karo did ordain Rav Moshe Alshich, who in turn ordained Rav Chaim Vital, but this chain of ordination did not continue.

This was, of course, not the end for Messianic expectations or attempts to renew semicha. In 1830, Rav Yisrael of Shklov, one of the primary students of the Vilna Gaon, made similar attempts to hasten the redemption through the reinstitution of semicha. The most serious, coordinated efforts, however, were launched following the establishment of the State of Israel.

In 1951, Rav Yehudah Leib Maimon convened a rabbinic conference in Tiberias to renew ordination for the State of Israel in the hopes of reestablishing the Sanhedrin. The location of the conference was no coincidence. Rambam writes that the Sanhedrin finally disbanded in Tiberias and will likely be renewed from there.

Rav Herzog, the Chief Rabbi at the time, was opposed to Rav Maimon’s efforts even though he himself struggled with integrating halacha into the land of Israel without an authoritative Sanhedrin. My friend and teacher, Rav Yaakov Sasson, uncovered previously unpublished correspondence between Rav Herzog and Rav Maimon, where Rav Herzog cautions Rav Maimon to tread lightly as he approaches this sensitive subject. This modern effort was not successful as most of the authoritative rabbis at the time, including the Chazon Ish and the Brisker Rav remained vehemently opposed.

Still, that hasn’t stopped further efforts to establish a Sanhedrin in Israel. In 2004, attempts were made—initially with Rav Adin Steinsaltz—to renew the Sanhedrin. These efforts did not bear any concrete results but their website continues to function: thesanhedrin.org.

Revoking Semicha

אם לא תשוב אל יהא לך מושך חסד אספי מארץ כנעתיך. הורד עדיך מעליך הסר המצנפת והרם העטרה. שמך לא נאה לך ואתה לא נאה לשמך. לא יהא לך זכרון אצל חכמי ישראל וימחה שמך מתקנותינו ואל יקרא שמך עוד הדובר רבי זמלין כי אם זמלין כאחד מן הריקים. וכן לס"ת אל יקראוך החבר אלא שמואל בר' מנחם וימחה שמך מלקרותך רבי.

שו"ת מהר"י וויל ס' קמ"ז

Just because modern-day semicha is not as authoritative as it once was, does not mean that revoking it would not be a seriously symbolic act.

The 15th-century rabbi, Yosef Colon ben Solomon Trabotto, known by the acronym Maharik, revoked the ordination of Rav Moshe Capsali from Constantinople, the Chief Rabbi of the Ottoman Empire. As detailed by Harry Rabinowicz, in his article “Joseph Colon and Moses Capsali,” through unreliable reports, Maharik came to the conclusion that Rav Moshe Capsali was issuing faulty halachic rulings, particularly regarding the laws of marriage and divorce. Maharik urged that Rav Kapsali should no longer be referred to as rabbi.

As it turns out, it was Maharik who was at fault, relying too much on faulty information about Rav Capsali’s rulings. Thankfully, the story does not end there. At the end of his life, Maharik realized he was at fault and sent his son Peretz to seek Rav Capsali’s forgiveness, which he dutifully gave.

Revoking semicha has continued in contemporary times.

Professor Jonathan Sarna, in his work American Judaism, mentioned that Yeshiva University “nominally revoked the ordination of graduates if they continued to serve mixed-seating congregations after having been warned to leave them.” Similarly, Rav Aharon Rakeffet recounts in his biography Bernard Revel: Builder of American Jewish Orthodoxy:

When a Yeshiva graduate refused Revel’s request to leave a position which had both mixed pews and a mixed choir, his ordination was revoked. Revel wrote to a graduate on September 19, 1933: “It grieves me to inform you that since you refuse to leave the Temple…where the sacred laws of traditional Judaism are violated, I urgently request that you return the conditional document of ordination that you received from the Yeshiva. The basic purpose of the Yeshiva is to guard the sanctity of Jewish Law in this land. If you will not return the document of ordination, I will be obligated to publish newspaper announcements declaring the nullification of your ordination.” The rabbi did not heed Rabbi Revel’s request, and the Yeshiva publicly announced the cancellation of his ordination and proclaimed that “one can no longer rely on his answers to inquiries of Jewish Law.”

The significance of semicha has certainly changed since its original institution, yet the importance of its bestowal—and revocation—remains until today.

And this brings us back to the original semicha, from Moshe to Yehoshua.

Moshe is instructed to give Yehoshua some of his glory (or authority), but not all of it.

The Talmud, cited in part by Rashi, explains why:

״וְנָתַתָּה מֵהוֹדְךָ עָלָיו״ – וְלֹא כׇּל הוֹדְךָ; זְקֵנִים שֶׁבְּאוֹתוֹ הַדּוֹר אָמְרוּ: פְּנֵי מֹשֶׁה כִּפְנֵי חַמָּה, פְּנֵי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ כִּפְנֵי לְבָנָה; אוֹי לָהּ לְאוֹתָהּ בּוּשָׁה, אוֹי לָהּ לְאוֹתָהּ כְּלִימָּה.

In a similar manner, you can say that God said to Moshe about Yehoshua: “And you shall put of your honor upon him” (Numbers 27:20), which indicates that you should put some of your honor, but not all of your honor. The elders of that generation said: The face of Moshe was as bright as the face of the sun; the face of Yehoshua was like the face of the moon. Woe for this embarrassment, woe for this disgrace.

There’s an obvious question here. Why did the elders begin to cry? Is it so bad that Moshe is like the sun and Yehoshua, his student, is like the moon? I would have thought that would be very moving imagery to explain the relationship of the first rabbi to his teacher Moshe.

The answer gets to the very heart of what being a rabbi is all about.

The Midrash explains why Moshe chose specifically Yehoshua:

לפי שהיה משה סבור שבניו יורשין מקומו ונוטלין שררותו התחיל מבקש מאת הקב"ה יפקוד ה', אמר לו הקב"ה משה לא כמו שאתה סבור אין בניך יורשין את מקומך אתה יודע שהרבה שרתך יהושע והרבה חלק לך כבוד והוא היה משכים ומעריב בבית הועד שלך לסדר הספסלין ופורס את המחצלאות הוא יטול שררות לקיים מה שנאמר נוצר תאנה יאכל פריה.

Yehoshua was not chosen because he was the smartest. Yehoshua was not chosen because he was the most popular. Yehoshua was chosen because each morning he would arrive early to the Beit Midrash and organize the chairs and tables to ensure people had a place to sit.

This is the difference between the light of the sun and the moon. The light of the sun is too strong—like a massive flame—to brighten a home. Moshe’s light, the midrash describes, was like a torch—powerful but not all that functional. The light of the moon is different, softer, and constantly changing. Yehoshua’s light was focused on illuminating the actual lived experiences of the Jewish People—through all their changes, struggles, and challenges. It was not a torch, it was the soft light of the moon that waxes and wanes. It was the organic light that would illuminate the natural lives of the Jewish People in Israel.

And this is why the elders began to cry. They were not weeping over the loss of Moshe but because they had discovered the light of Yehoshua. They felt disgraced, realizing they lacked the traits Yehoshua exemplified. It was not just through impressive scholarship and revelatory drashos that Yehoshua distinguished himself—it was through his care and concern for the Jewish People.

When Moshe rested both of his hands on Yehoshua he was deliberately invoking the image of a korban (sacrifice). Yehoshua was not an actual korban—though some have described the rabbinate that way—instead it was through Yehoshua’s sacrifice on behalf of the lives of the Jewish People that he merited to be the first person ever to receive semicha.

Rav Chaim Soloveitchik, the famed genius rav of Brisk, was once asked to describe the job of a rabbi. He did not respond by discussing his brilliant interpretations on the Rambam. “The job of a rabbi,” Rav Chaim responded, “is to help the poor, widows, and orphans.” On Rav Chaim’s tombstone, the first superlative he is described with is “Rav Chessed,” a rabbi of loving-kindness.

Semicha has indeed changed quite a bit, but its initial goal—uplifting the Jewish People—remains ever the same.

Shabbos Reads — Books/Articles Mentioned

The Grandfather I Thought I Knew, Elana Moskowitz

Rabbinical Authority and Authorization in the Middle Ages, Jacob Katz

Semicha: Then and Now, Herschel Schachter

Can Semikha be Renewed Today?, Shimshon Nadel

Maimonides on the Renewal of Ordination, Gerald Blidstein

The Dispute between Jacob Berab and Lev ben Habib over Renewing Ordination, Jacob Katz

Hastening Redemption: Messianism and the Resettlement of the Land of Israel, Arie Morgenstein

The Invention of Jewish Theocracy: The Struggle for Legal Authority in Modern Israel, Alexander Kaye

Gems from Rav Herzog’s Archive (Part 2): Sanhedrin, Dateline, the Rav on Kahane, and More, Yaacov Sasson

Joseph Colon and Moses Capsali, Harry Rabinowicz

Revoking Ordination, Gil Student

American Judaism, Jonathan Sarna

Bernard Revel: Builder of American Jewish Orthodoxy, Aharon Rakeffet

Check out All Parsha, where you can find weekly audio of Reading Jewish History in the Parsha, as well as other incredible presenters and amazing features that will enhance your Parsha journey!

Reading Jewish History in the Parsha has been generously sponsored by my dearest friends Janet and Lior Hod and family with immense gratitude to Hashem.