The accompanying shiur is available on the Orthodox Union's parsha learning app: All Parsha.

Some jokes become so common and cliché that they serve more as social commentary than a recipe for laughter.

And particularly with Jewish jokes—especially the ones you’ve heard before—it’s less about the laughter the joke provokes (not much) and more about what the joke says about those who tell it and understand it.

So, with that unfunny introduction, here is a not-so-funny joke you’ve most likely heard before:

A Jewish man has been stranded on a island alone for 20 years. Finally, he is rescued.

The Jewish man insists on showing his rescuers the life that he has built for himself on the island.

They come across a small clearing with a bunch of makeshift buildings.

He points to the closest one, “That’s my home.” He continues to point to the other buildings as they walk by.

“There’s the supermarket. And the bank. And the saloon. Over there is my synagogue, where I went to pray that someone would come rescue me.”

A rescuer pointed to a lone building away from the rest. “And what’s that?” The Jewish man disdainfully says “Oh, that. That’s the other shul. We don’t go there.”

As I said, you probably heard it before.

But it is interesting that Jews are so known for break-off shuls and side minyanim, considering there seems to be an explicit prohibition exactly for that type of behavior.

In our parsha, we find the following:

בָּנִים אַתֶּם לַה’ אֱלֹהֵיכֶם לֹא תִתְגֹּדְדוּ וְלֹא־תָשִׂימוּ קׇרְחָה בֵּין עֵינֵיכֶם לָמֵת׃

You are children of your God. You shall not gash yourselves or shave the front of your heads because of the dead.

The Talmud interprets לא תתגדדו, which in plain translation means not to make a gash during a time of mourning, as also including a prohibition against breaking off from the central community.

(As an aside, I never understood the practice of cutting oneself while in mourning until I watched Kevin Costner in the titular role in Robin Hood Prince of Thieves cut his hand after the murder of his father)

Why does the Talmud find an allusion to not separating from the mainstream community from a verse that seems to be about not cutting oneself while in mourning?! These two actions seemingly have nothing to do with each other.

To understand this, let’s explore the history of the schism of Hungarian Jewry and the emergence of the Orthodox community.

The Hungarian Jewish community in the mid-nineteenth century did not take to reforms in Jewish life kindly. The legacy of the Rav Moshe Sofer, known as the Chassam Sofer, still hovered in the collective memory of communal leaders well beyond his passing in 1839.

His classic pun, “chadash assur min HaTorah” — a principle about eating grains from the new harvest (known as chadash) was applied instead to oppose all innovations in Jewish life and practice. During his lifetime, the Chassam Sofer battled against figures like Rabbi Aaron Chorin, whose ritual innovations were seen by the Chassam Sofer and his students as uprooting traditional Jewish life and practice. Of course, the Chassam Sofer himself was extraordinarily creative and innovative in his approach to Torah, but he still took a firmly conservative approach to those whose innovations were seen as threatening to the very foundation of traditional Jewish life.

Following the death of the Chassam Sofer, the traditional Jewish community had opposing factions on how to approach those advocating for more radical reforms in Jewish practice and Jewish life. Rav Azriel Hildesheimer advocated for a more conciliatory approach—favoring the idea of rabbis who were proficient in both traditional Torah learning as well as some of the more modern academic methods. He was vehemently opposed by many students of the Chassam Sofer including Rav Akiva Yosef Schlesinger, who studied under the son of the Chassam Sofer. Meanwhile, some reformers opposed both more traditional schools, such as Rabbi Leopold Löw. He championed a school of reform that was somewhat grounded in tradition—at least in contrast to more radical reformers in Germany and the United States—but used academic approaches to advocate for a more flexible and progressive interpretation of Jewish law.

Eventually, these warring factions led to the official schism of Hungarian Jewry in the 19th century. The Orthodox community sought to strictly adhere to traditional Jewish law and practices, rejecting modern influences. In contrast, the Neologue community embraced moderate reforms, such as adopting some aspects of modern culture and adjusting religious practices to fit contemporary life while still maintaining Jewish identity. The Status Quo community emerged as a middle ground, not aligning fully with the Orthodox or Neologue movements, and preferred a more flexible approach to religious observance. This division formalized after a government-mandated Congress in 1868-69 created lasting tensions and separate institutional structures within Hungarian Jewry.

For a while, these divisions were a feature of Hungarian Jewry, with little parallel on American soil, where nearly all Jews agreed in some measure to interact with modernity and American culture. That all changed, however, in 1928 with a curious exchange in a little-known Torah journal called Apiryon.

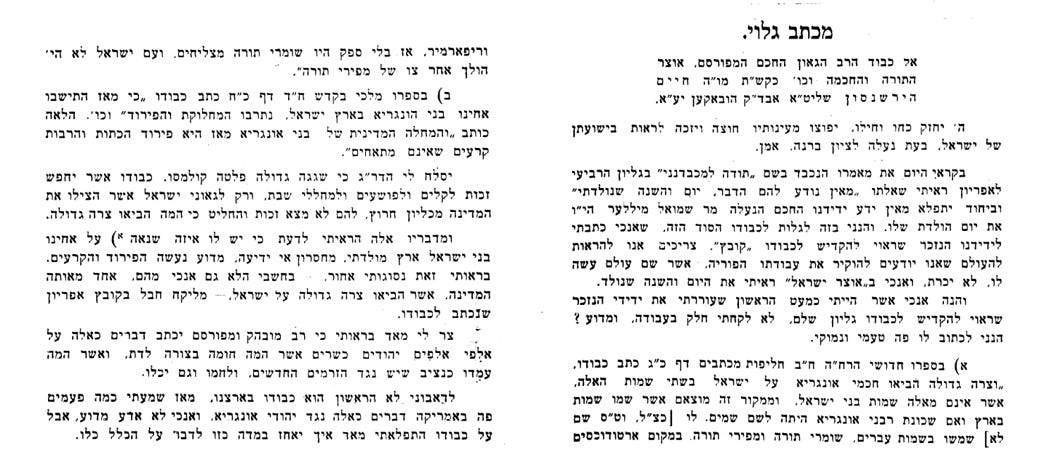

As discussed by Professor Adam Ferziger in his fantastic book, Beyond Sectarianism: The Realignment of American Orthodox Judaism, a letter was published in the journal Apiryon that was written by Rav Yekusial Yehudah Greenwald that was addressed to Rav Chaim Hirschenson.

It is a bit of a strange letter. It begins with an explanation as to how the editors of the journal knew to offer special birthday wishes to Rav Hirschenson, who had recently celebrated his 70th birthday. Rav Greenwald explained in his letter that it was, in fact, he who supplied Rav Hirschenson’s birthdate allowing for the glowing 70th birthday wishes. Then the letter takes a turn. Rav Greenwald explains why he himself did not participate in Rav Hirschenson’s birthday celebration despite the fact that the entire celebration had been his idea. Rav Greenwald writes—as translated by Professor Ferziger:

I did not participate in this work, why? . . . In your talmudic novellae . . . you wrote ‘‘And terrible trouble was brought by the Hungarian sages upon Israel . . .’’ [and] in the fourth volume of your work Malki ba-Kodesh . . . you recorded that ‘‘Ever since our brothers the sons of Hungary settled in the Land of Israel, infighting and division have grown . . . sectarian dissention and multiplication of irreparable splits has long been the national sickness of the children of Hungary.’’ Forgive me honorable one for your pen has spilled an inadvertent sin. You that labors to find goodness among the lighthearted evildoers who publicly desecrate the Sabbath, while regarding the brilliant rabbis of Israel that saved the country from total destruction, you find no redeeming qualities? . . . From these words I could only conclude that you possess hatred toward our brothers, the children of Israel from my birthplace, that stems from ignorance as to the reason for the division and the fissures. When I recognized this I made an about face—for I thought, am I not one of them, a person from that same country that brought terrible misery upon Israel?

At the heart of their debate was the merits of the Hungarian Jewish communal model. Interestingly, neither rabbi could be characterized by the more hardline conservative Orthodoxy of Hungary—both were somewhat moderate in their respective approaches to American Jewry. Rav Hirschenson, who was more than three decades older than Rav Greenwald, served as a Rav in Hoboken, New Jersey, where he was an early proponent of Religious Zionism and engaged with many of the secular trends of modernity sweeping the nation—egalitarianism, democracy, technology, and scientific discovery. Rav Greenwald was not exactly the paradigm of classic Hungarian traditionalism himself, despite his strong defense of their approach. As a Rabbi in Columbus, Ohio’s Beth Jacob, he invited Golda Meir to speak and even allowed separate seating without a mechitzah. On some matters, however, his uncompromising Hungarian approach from his upbringing was evident—he was extraordinarily strict on the laws of Shabbos, admonishing kosher butchers who opened their stores too soon after Shabbos. He excommunicated and burnt the siddur of Reconstructionist founder, Rabbi Mordechai Kaplan. Once, after learning a congregant had driven to shul, he canceled an entire series of Friday night lectures.

Despite his openness relative to the actual Hungarian model, Rav Greenwald still yearned for a more authentic expression of Jewish life in America. He was extraordinarily suspicious of the emerging Modern Orthodox approach in America, which seemed to him to compromise far too much for modern sensibilities.

In the introduction to Rav Greenwald’s work Ach L’tzarah, he minces no words in his disdain for Modern Orthodoxy:

I myself have heard a speaker who is known by the title rabbi that when eulogizing before the deceased spoke of the greatness of the Russian author Tolstoy. Once upon a time the children of Israel knew well that those who act in this way were called free thinkers, or the deviants of Israel, Reformers, who have no place among the kosher Israelites. Today, however, they speak in the name of Modern Orthodoxy, and the rabbi is Modern Orthodox, which means that he has the right to change, limit, or add as the times demand as long as he is called Orthodox.

He elaborates, somewhat comically, in a footnote about the ills of Modern Orthodoxy:

Modern Orthodoxy, a plague that does not appear in the Bible . . . they destroy all that is holy to us. On Sabbath evening they gather in the synagogue, arriving in automobiles, they park on all of the surrounding streets. The entire congregation sings tunes, women and men together, young ladies and women chant in front of the Holy Ark and the Modern Orthodox rabbi babbles about Spinoza, Schopenhauer, and other such friends. This is their Sabbath evening worship of God and they throw their spears on all who try to speak out against them . . . They eat their meals anywhere and even in the homes of women who desecrate the Sabbath in public . . . They also belittle the adultery laws and without proper investigation and testimony they declare a women to be eligible for marriage.

While this is not the first time the term “Modern Orthodox” appears, it was used here likely for the first time as a derisive label distinct from the more authentic Orthodoxy Rav Greenwald remembered from his youth in Hungary.

As Professor Ferziger explains:

In applying this latter tag to his adversaries Greenwald established that they were different from both the Reform and Conservative, but he simultaneously distinguished them from ‘‘true’’ or ‘‘authentic’’ Orthodox Jewry. This served him well, for it provided a clear branding for those who deviated from his traditionalist European style Orthodoxy. No longer did he need to complain about these figures and congregations usurping the name ‘‘Orthodox.’’ Rather, by highlighting the formal category of ‘‘Modern Orthodox,’’ he could spare the genuine Orthodox being classified in one broad rubric with less committed Jews. No training could have schooled him better for intuiting this boundary definition tool than his own upbringing in the heart of Hungarian Orthodoxy.

Questions of separatism continued to haunt the Orthodox Jewish community long after the passing of both Rav Hirschenson (d. 1935) and Rav Greenwald (d. 1955). In June 1956, a year after Rav Greenwald’s passing, a psak din (halachic ruling) was published in HaPardes, a popular rabbinic journal, by the leading American Roshei Yeshiva at the time forbidding participation in the Synagogue Council of America, an umbrella organization that included both Orthodox and non-Orthodox rabbis. Noticeably absent from the Roshei Yeshiva who signed was Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, a Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshiva University and acknowledged leader of the Modern Orthodox community.

As detailed by Jonathan J. Golden in his dissertation, “From Cooperation to Confrontation: The Rise and Fall of the Synagogue Council of America,” there was a significant amount of behind-the-scenes politics that marginalized Rabbi Soloveitchik despite his deep relationships with his fellow Roshei Yeshiva. Still, what was done was done and their differing approaches to the contours of Orthodox cooperation with the non-Orthodox world opened up deeper fissures within the Orthodox world that are still felt today. The question remains: How insular should the Orthodox community be?

In a Jewish Action Review of the collected writings of Rabbi Soloveitchik, Rav Moshe Meiselman, Rav Soloveitchik’s nephew, reflected on the aftermath of the Synagogue Council controversy:

The few letters in the volume regarding the issue of the Synagogue Council are but a tip of the iceberg of one of the major issues in Orthodox Jewish life of the ‘50s. Unfortunately, the time has not yet come when the background and details of this controversy can all come to the fore. In 1956, a letter was signed by eleven of the leading roshei yeshivah of the United States forbidding participation in rabbinic or synagogue groups together with members of the Conservative and Reform movements. This would have meant that members of the Rabbinical Council of America (RCA) could no longer be members of the Board of Rabbis—a mixed group—and that the Orthodox Union would no longer be able to continue its longstanding affiliation with the Synagogue Council of America. The letters of the Rav in this volume reflect that the publication of the issur (prohibition) of the eleven roshei yeshivah came as a surprise to the Rav. In the time immediately preceding the publication of the issur there was an intense dialogue between the Rav and Rav Aharon Kotler on reaching a compromise text, to which the Rav could be a signatory. Both of these gedolim were interested in avoiding the divisions within the Orthodox community that would result from the lack of a compromise. There were two other individuals whose political interests were served by a lack of compromise. These individuals published the earlier text, thereby aborting the dialogue about a compromise text. The Rav never forgave these two individuals for creating the unfortunate tensions and acrimony that resulted from the lack of a compromise text. One can debate whether the Orthodox community gained anything from the participation of the RCA in the Synagogue Council. However, the isolation of the Rav from the rest of the yeshivah world as a result of this controversy was certainly a tragedy that greatly limited his participation in, and impact on, the general yeshivah world.

And this brings us back to our parsha.

בָּנִים אַתֶּם לַה’ אֱלֹהֵיכֶם לֹא תִתְגֹּדְדוּ וְלֹא־תָשִׂימוּ קׇרְחָה בֵּין עֵינֵיכֶם לָמֵת׃

You are children of your God. You shall not gash yourselves or shave the front of your heads because of the dead.

The prohibition of separating from the community is couched within a verse whose plain meaning is discussing cutting oneself in mourning.

What do these prohibitions have to do with one another?

The answer lies at the beginning of the verse: You are all children of God.

How does this reason explain either prohibition—cutting during mourning or creating a separatist community?

At the heart of this statement—that the Jewish People are described as the children of God—is our distinct embodiment of transcendence and eternity. נצח ישראל לא ישקר—the eternity of the Jewish People is undeniable.

It is for this reason that we are cautioned against excessive mourning. Of course, it is ok to be sad, but excessive mourning evinces a detachment from the reality of the eternity of the Jewish soul and the Jewish People. A reminder that we are the children of Hashem is the very reason why our mourning should never become self-harm since a part of each of us continues within the eternal family that is the Jewish People.

And this is the very reason why we are cautioned from separating from the community. A family sticks together. Our differences—as long as they do not threaten the very essence of Jewish life—can be bridged. To remain part of Knesseth Yisroel—the collective soul of our people—is not merely a choice but a calling, reminding us that unity can prevail over division and that the ties that bind us are stronger than the disagreements that divide us.

Bonus Addition: Curb Your Parsha Enthusiasm

Parshas Re’eh is also the source for the prohibition of Yichud, secluding oneself with a sexually forbidden member of the opposite gender.

In the 8th episode of the 5th season of Curb Your Enthusiasm there is a fascinating episode that discusses this prohibition. Larry David, who is pretending to be Orthodox is stuck on a ski lift with Rachel Heineman, a genuinely frum woman. As it gets darker and darker the woman starts to worry. Here is the dialogue from the scene:

Larry: What's going on?

Rachel: Shkiyas hachama. That's what's going on here.

Larry: What?

Rachel: Shkiyas hachama. Sundown. I can't be here alone with you after sundown.

Larry: Why not?

Rachel: Because you're a man and I'm a single woman. So? So it's not allowed.

Larry: Who says so?Rachel: The law, the Torah says so. Hashem says so.

Larry: Hashem?

Rachel: Do you know anything?

Larry: No, Hashem, I know. Anyway, it's okay. There's extenuating circumstances here.

Rachel: No such thing as extenuating circumstances.

Larry: Well, you got another half hour.

Rachel: 5:41. Shkiyas hachama is at 5:41.

Larry: All right well, that's a half hour.

Rachel: Just tell me how much time we have left.Larry: Well, I think you got about two minutes.

Rachel: Oh. Somebody's gonna have to jump.

Larry: Oh, stop.

Rachel: Stop what? I can't be here with you after sundown! There's no other way. Somebody's gonna have to jump! You're gonna have to jump! Are you gonna jump?

Larry: What, are you —— nuts? What? What are you doing? No, no!

It is a fascinating halachic question. Was Rachel Heineman correct—does one have to risk giving up their lives rather than violate the prohibition of yichud? This is a much larger discussion that my dearest friend, Rabbi Jake Sasson has written about in an unpublished essay analyzing the halachic principles of this episode of Curb.

But even more fascinating is that this is based on a true story!

Ruth Friedman, whose married name at the time was Ruth Eider, jumped off of a ski lift rather than violate the principles of yichud. She, represented by her father later sued in court. An August 1967 court decision ruled in her favor.

One question that always bothered me: How did Larry David hear about this lawsuit and court case? Surely, it could not be a coincidence that he wrote an episode about this exact scenario.

The answer is even more wild.

And, it involved—you definitely did not have this on your bingo card—RFK Jr., who recently dropped out of the presidential race. In an interview in Tablet Magazine RFK Jr., who is married to Curb actress Cheryl Hines, explained how he served as the source for this famous episode:

You are the source of another Curb Your Enthusiasm episode, right, which is very famous among Orthodox Jews, which is the one with the girl who’s stuck in the ski lift for Shabbat, the Sabbath, and then has to jump down.

Yeah. My first lawsuit when I was a summer associate at a law firm in New York, my first client was somebody who had been injured at a ski area. And the states that have ski areas normally pass shield laws, because the ski areas are huge economic drivers for the state, and they know a lot of people are going to get injured. They pass shield laws to make sure the ski areas are not just barraged in a deluge of lawsuits all the time.

So I was looking through the law books to try to find some precedent where anybody had successfully sued a ski area in New York, and I found this case, the only case I could find, which was two Hasidic Jews who got on a chair lift at the Bellayre area in the middle of the summer, and they were going to ride the ski lift up, and then they were going to hike down, which is a common thing that people do in the summer. You get a nice walk, but it’s all downhill. And the guy at the bottom had told the guy at the top, there’s a couple who just got on, and it was at the end of the day. So the guy at the top let a couple off, and shut off the lift. And he hiked down and he left these two people, the Hasidic couple, up on the lift. And it was at the highest point in the lift.

And in the Hasidic tradition, an unmarried male and female can’t be with each other after sundown. But the stigma’s on the woman. So there was an argument between them where she was trying to convince him to—

Jump.

And he refused to do it. And I told that to Larry and he thought that was the funniest thing he ever heard.

It is quite funny.

And then she did jump. And then she was grievously injured, and she successfully sued the ski area. But he didn’t believe it. And about a month later, somebody from his office called me and said, “Can you find that case?” Because he was checking.

This doesn’t quite relate to Jewish history, but I could not resist sharing. Maybe in future years when we do Pop Culture in the Parsha we can elaborate further.

Shabbos Reads — Books/Articles Mentioned

A House Divided: Orthodoxy and Schism in Nineteenth-Century Central European Jewry, Jacob Katz

Beyond Sectarianism: The Realignment of American Orthodox Judaism, Adam Ferziger

Hungarian Separatist Orthodoxy and the Migration of Its Legacy to America: The Greenwald-Hirschenson Debate, Adam Ferziger

From Cooperation to Confrontation: The Rise and Fall of the Synagogue Council of America, Jonathan J. Golden

Review of Community, Covenant and Commitment: Selected Letters and Communications, Moshe Meiselman

Check out All Parsha, where you can find weekly audio of Reading Jewish History in the Parsha, as well as other incredible presenters and amazing features that will enhance your Parsha journey!

Reading Jewish History in the Parsha has been generously sponsored by my dearest friends Janet and Lior Hod and family with immense gratitude to Hashem.

Wow, what a story from Rabbi Meiselman about Rav Soloveitchik and Rav Kotler's discussion on the ban. I'm so curious who are those "two individuals."

Wow, I can't believe that Curb episode was based on a true story!