The accompanying shiur is available on the Orthodox Union's parsha learning app: All Parsha.

Yosef was finally seeing his dreams realized.

All of his brothers were beseeching him for mercy, bowing before him, just as his youthful dreams had predicted. Still, Yosef was not fully satisfied. Binyamin was missing, and his earlier dreams had shown a vision of all the brothers bowing before him. Yosef was on a mission, and he knew these dreams needed to be fulfilled. They were part of a much bigger plan.

In fact, Ramban explains, this is why Yosef never contacted Yaakov the entire time he was in Egypt. Even though he was only a few-days journey away, he never sent a message or checked on his father because he understood how important it was for his dreams to be realized. Yosef did not want to interrupt the unfolding of his dreams.

Looking back at the trajectory of Yosef’s life, we find something quite curious. The first half of Yosef’s life—his earlier dreams, led to him being sold into slavery, alienated from his family, fleeing from the house of Potifar, and ultimately alone in an Egyptian jail. The next chapter, however, is full of greatness—redemption from prison, rising to the top of Egyptian political power, and ultimately saving the country from famine.

What is the explanation for the disparity in the narrative of Yosef’s life?

To understand all of this, let’s explore a chapter in Chassidic history—a battle of the ownership of the Chabad library.

It was not a given that Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson would assume the mantle as the seventh Rebbe of Chabad. His father-in-law, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneerson, known as the Rebbe Rayatz, passed away on 10th of Shevat, 1950. An entire calendar year went by until Rabbi Menachem Mendel agreed to assume the leadership of the chassidim. He relented on the 10th of Shevat of 1951. After being presented with a letter from his chassidim beckoning him to accept, he finally agreed. “You all have to help me,” the Rebbe insisted.

The previous Rebbe had two daughters in America; his third daughter, the youngest, Shaina, was murdered in the Holocaust. His oldest daughter, Chana, married Shmaryahu Gurary, known as the Rashag. His middle daughter, Chaya Mushka, married Rabbi Menachem Mendel, who eventually became the Rebbe. But the Rashag was five years older than the eventual Rebbe and had taken on a significant amount of leadership responsibilities within the movement. Moreover, the Rashag had a son—Barry, who could serve as an eventual heir to Chabad leadership. The Rebbe and Rebbetzin were never blessed with children.

After the Rebbe assumed the mantle of leadership in 1951 with his famous maamar (a traditional chassidic discourse), “I have come into my garden,” the chassidim were ecstatic. Even his older brother-in-law, the Rashag, eventually embraced his leadership. His son, Barry, however, still felt spurned. While he would continue to visit 770, the headquarters of Chabad, he never accepted his uncle as Rebbe. As Chaim Miller reports in his biography, Turning Judaism Outwards, the custom at the Rebbe’s Passover Seder was for no one to lean in front of the Rebbe as a sign of respect. “At the Rebbe’s Seder in 770,” Miller writes, “none of the attendees leaned—except for Barry.”

Beginning in 1984, the divisions within the family grew far more serious. In need of extra money, Barry Gourary began sneaking into the library of his grandfather, the Rebbe Rayatz, and surreptitiously removing valuable books to resell. In early 1985 it became noticeable that valuable books from this historic library were missing. A video system was installed in order to discover the identity of the thief. Lo and behold, they discovered the culprit: Barry Gourary, the Rebbe’s nephew.

The Rebbe was distressed. This was about more than books. Stealing books for resale from the Chabad library was a challenge to the very authenticity of the Rebbe’s leadership. Was he, in fact, the 7th Rebbe of Chabad, or had the movement died along with his father-in-law, the Rebbe Rayatz, the 6th Rebbe?

As soon as the theft was realized a public statement was issued by Chabad warning people not to purchase the stolen books.

Barry Gourary stole over 500 books from the library. Of those, he sold 102. Chabad coordinated an effort to repuchase the stolen books. They were able to buy back almost all of the ones sold—94 out of 102—for $433,000.

Rabbi Moshe Bogomilsky, a dedicated chassid of the Rebbe, led much of the effort to track down and retrieve the stolen books. He enlisted the help of Rabbi Menashe Klein, Rav of Ungvar, to urge those who purchased stolen books to sell them back to the Chabad library. In Rabbi Bogomilsky’s memoir, he recounts that Rav Menashe Klein was shocked at how valuable some of these works were. When Rav Menashe Klein learned that the stolen 1760 Kitzee Haggadah was sold for nearly $150,000, he exclaimed, “Vos?! $150,000 far a Haggadah, zicher Pharoah hut alein ge’chasmet zein numen off es” (“What?! $150K for a Haggadah—must be Pharaoh himself signed it!”).

In December of 1985 the dispute was brought to the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York. Agudas Chasidei Chabad v. Gourary would decide who owned the books and, in a larger sense, who was the rightful heir to Chabad.

Chabad was represented in court by Nat Lewin. The judge in the case, Charles P. Sifton, was the son-in-law of the famed theologian Reinhold Niebhur, who composed the Serenity Prayer popularized at Alcohol Anonymous meetings. Lewin was relieved that the judge was connected to such a theologian given the many theological undertones to the case.

At the heart of Chabad’s claim was that the books did not belong to the Rebbe as an individual but rather to the chassidic movement as a whole, therefore even Barry Gourary, a grandson, had no claim. To bolster Chabad’s position they pointed to several letters of the Rebbe Rayatz, which explicitly indicated that his library belonged to the chassidus. One letter, sent by the Rayatz in February of 1946 to Dr. Alexander Marx, head librarian of the Jewish Theological Seminary, in the hopes of enlisting his help retrieving books that remained in Europe, explicitly states, “These books are the property of Agudas Chasidei Chabad of America and Canada."

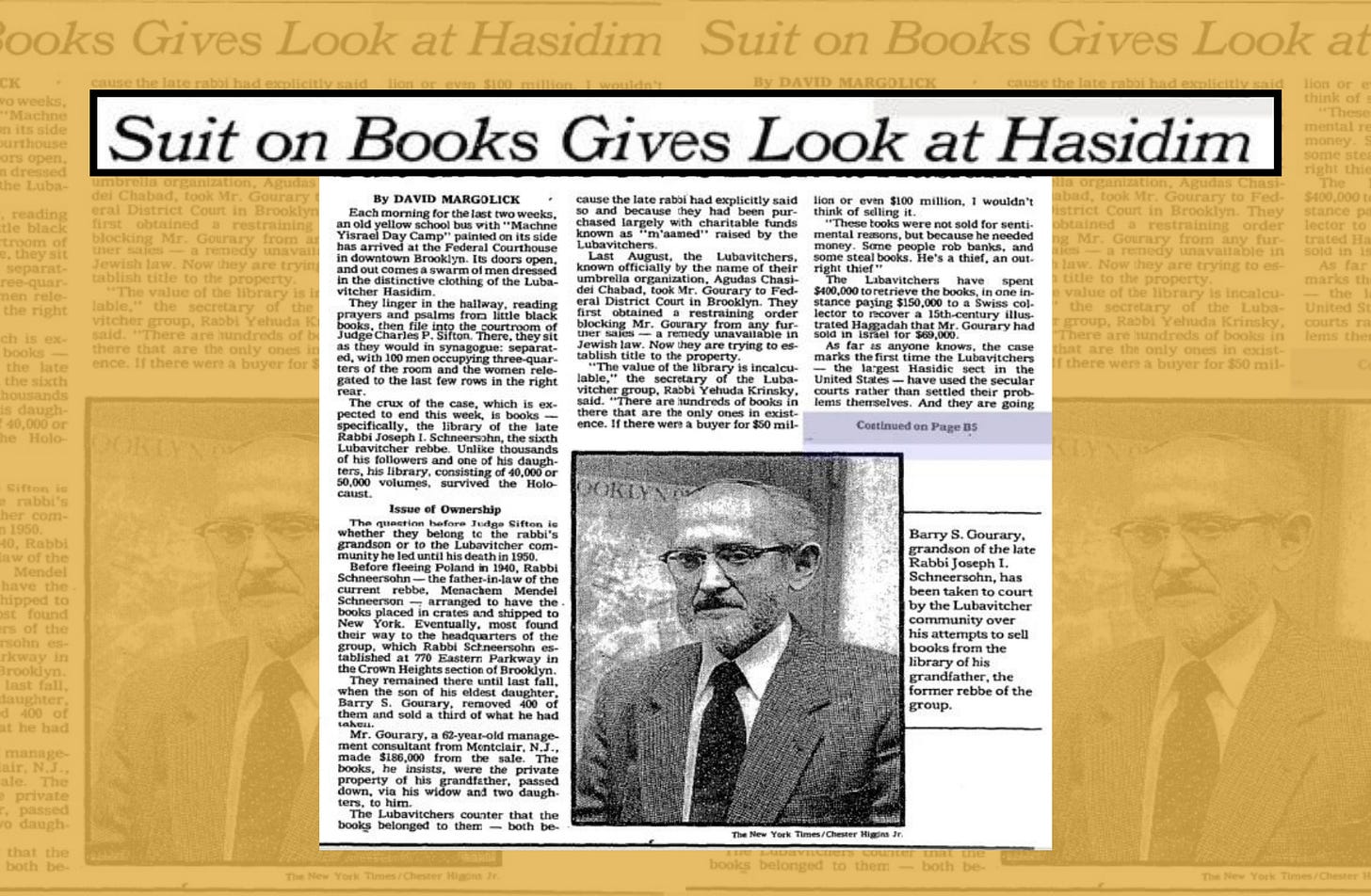

The case captured the nation.

For many, this was their first glimpse into the inner workings and structure of Hassidic communities. The December 18, 1985 New York Times headline read, “Suit on Books Gives Look at Hasidim.”

The Rebbe declined to participate in any depositions related to the case. His wife, however, Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka, wife of the Rebbe and daughter of the previous Rebbe, was deposed for over an hour. The video footage is still available online.

When the Rebbetzin was asked whether she thought the library belonged to the Rebbe or the Chassidim, her response was poignant. “It was for the chassidim,” she explained, “since my father belonged to the chassidim.”

In order to explain to Judge Sifton the nature of Chassidic movements in general and the Chabad movement in specific, Chabad turned to Rabbi Louis Jacobs who provided testimony to the court based on his extensive scholarship. His testimony was later published along with a foreword by Nat Lewin and a preface by my dearest friend Menachem Butler. In his preface, Lewin acknowledges that Rabbi Jacobs was a controversial choice, given the outcome of the Jacobs Affair when he was rejected from becoming the Chief Rabbi of England, but they remained confident that he would have the scholarly acumen to make the case for Chabad.

Rabbi Jacobs’s testimony is nearly 200 pages of court transcript. Throughout, Rabbi Jacobs gives a masterclass on the nature of Chassidic movements. He states emphatically, “It is true that you can’t have a chasid without your Rebbe—But you can’t have a Rebbe without chassidim.”

On January 6, 1987, the 5th of Teves, the court ruled in favor of Chabad. The books belonged to the Chassidim. The Chassidim, in a sense, vindicated the leadership of their Rebbe. “Didan netzach,” chassidim exclaimed, we won!

The Rebbe proclaimed the 5th of Teves an ongoing day of celebration of books and Torah learning. He urged his chassidim to buy books, learn from holy books and continue in the work of Yosef—both the Biblical personality and a reference to his father-in-law’s, the Rayatz, first name.

“Torah and Yiddishkeit should be spread,” the Rebbe urged, “and our wellsprings should go outwards—to the point where nothing else lies beyond.”

There’s an old Chassidic tale, I think I first heard from Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski.

A chassid walks into his rebbe’s chambers and says, “I think I am ready to start my own chassidic movement.”

The rebbe asks, “How do you know this?”

“Well,” the chassid explains, “every night I have a vivid dream that I am a rebbe for 300 chassidim.” Surely, this recurring dream must be a sign.

The Rebbe smiles.

“You don’t start your own chassidus when you have a dream that you have 300 chassidim—you start your own movement when 300 chassidim have a dream that you are the Rebbe.”

A rebbe’s dreams is not for himself but rather for the self-actualization of the movement.

And this distinction stands at the heart of the story of Yosef. His entire life is spent dreaming. But the first chapter of his life—jealousy of the brothers, sold into slavery, escape from Potifar’s home, and jail—drastically differs from the leadership and power of the second half of his life.

What is the difference?

The first half of Yosef’s life he was preoccupied with his own dreams, in the second chapter of his life Yosef begins to interpret the dreams of others.

True leadership is not fulfilling our dreams, but like the Biblical Yosef and Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneerson, leadership is about helping others actualize their dreams.

Shabbos Reads — Books/Articles Mentioned

Turning Judaism Outward: A Biography of the Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson, Chaim Miller

Hei Teves Didan Netzach: The Victory of the Seforim, Moshe Bogomilsky

The Original 1985 Courtroom Testimony in the Trial of Agudas Chasidei Chabad vs. Rabbi Sholom Dovber (Barry) Gourary, eds. Menachem Butler and Ivor Jacobs

Check out All Parsha, where you can find weekly audio of Reading Jewish History in the Parsha, as well as other incredible presenters and amazing features that will enhance your Parsha journey!

Reading Jewish History in the Parsha has been generously sponsored by my dearest friends Janet and Lior Hod and family with immense gratitude to Hashem.