Yosef's Ambiguous Apology

On Vayigash and two of Rav Kook's famous (and controversial) speeches

The accompanying shiur is available on the Orthodox Union's parsha learning app: All Parsha.

At long last Yehudah confronts his brother Yosef.

After being sold into slavery, exiled from his brothers, they are reunited. Yehudah confronts Yosef. And, in one of the most moving scenes in the entire Torah, Yosef clears the room of all of his advisors and finally reveals his identity to his brothers.

“I am Yosef your brother,” he says, “Is our father still alive?”

Don’t be distressed that you sold me into slavery, Yosef says as he comforts his brothers, this was all part of the divine plan.

It seems like a moving reconciliation. Everyone is good now, right?

Not quite.

If you read the Torah carefully, as Rabbeinu Bachye notes, Yosef never formally forgives his brothers for selling him into slavery. Yes, they came together. And yes, Yosef hugs Binyamin and kisses his brothers, but there is no formal declaration of forgiveness. Is hugging it out enough?

Rabbeinu Bachye does not seem to think so. He writes (Genesis 50:17):

The Torah does not spell out that Joseph actually forgave his brothers. Our sages (Bava Kama 92) point out that if a person has wronged his fellow man and regrets this wrong and determines not to act in the manner which had offended his fellow man he is not forgiven by God until after he has made an effort to obtain forgiveness by the aggrieved party first. At any rate, the Torah is not on record anywhere that Joseph did forgive his brothers. This was the reason why the sin committed against Joseph resulted in the ten martyrs being executed by torture at the hands of the Romans.

Seemingly, hugging it out is not, in fact, enough to grant forgiveness.

Interestingly, Rashi was asked this very question in a responsa (#245). There is no greater form of reconciliation, Rashi writes, than giving a hug and a kiss.

The reconciliation between Yosef and his brothers is left ambiguous. There was a kiss, there was an action, but no formal declaration. They acted conciliatory towards one another but, as Rabbeinu Bachye notes, Yosef’s heart was not fully mended.

Why is the denouement of this harrowing story so unclear? When will Yehudah’s confrontation with Yosef finally be resolved?

To understand this conclusion, let’s explore two incidents that contributed to much of the enduring controversies surrounding the legacy of Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook (1865-1935).

Rav Kook’s vision for a redemptive reconciliation among all the Jewish people was never realized. Instead, throughout his life, particularly after being appointed as the first Chief Rabbi of Palestine in 1921, he became a magnet for controversy.

Rav Kook’s life and legacy should never be reduced to the controversies that surrounded him, but in many ways, they are a lens to better understand what he was trying to accomplish. For those looking for a more comprehensive yet accessible overview of his life, I would urge you to read Yehudah Mirsky’s biography, Rav Kook: Mystic in a Time of Revolution.

Yet even from the controversy and criticism directed at Rav Kook one can appreciate his goals and dreams.

Following a 1921 visit to the land of Israel, Rav Avraham Mordechai Alter, the second Rebbe of Ger, known as the Imrei Emes, wrote a letter on his boat ride home reflecting on his meeting with Rav Kook. “Also it is public knowledge that he loathes money,” the Imrei Emes writes, “However his love for Zion surpasses all limit and he declares the impure pure.” Deliberately invoking the image of Rebbe Meir, one of the Mishnaitic sages, the Imrei Emes, while moved by Rav Kook’s works was concerned by his sensitivity to communal boundaries. As Bezalel Naor painstakingly details in his translation and commentary of Rav Kook’s Orot, Rav Kook throughout these controversies evinced “a noble tranquility of spirit.”

Theodore Herzl died on July 3rd, 1904 at the age of 44. In one of Rav Kook’s earliest controversies, he was asked to give at a memorial service for Herzl. Herzl, of course, was not an observant Jew, though his contributions to Judaism and the Jewish people were enormous. Rav Kook, who was recently appointed the Rabbi of Jaffa, was asked to offer words in a memorial service for Herzl. This put Rav Kook in a tough spot—it was unusual for a rabbi of his stature to eulogize a secular Jew, yet he also knew that refusing to give a eulogy would cause its own controversy. As Bezalel Naor details in his book When God Becomes History: Historical Essays of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook, there was no satisfactory solution.

Instead, Rav Kook memorialized the spirit and mission of Herzl, but not once throughout his speech does he explicitly mention Herzl. Instead, he focuses on a prophecy of Zecharia about a future eulogy that would one day take place in Jerusalem. The Talmud (Sukkah 52a) explains that Zecharia’s prophecy was about the eulogy for the death of Messiah son of Yosef.

Rav Kook’s eulogy for Herzl details his vision for Zionism couched in the personalities of Yehudah and Yosef. In Jewish tradition, we are told that there will be two messianic personalities: Messiah ben Yosef and Messiah ben Yehudah. Each represents a different aspect necessary for redemption—Yosef is universalist material success, while Yehudah represents particularistic spiritual grandeur. As Rav Kook explains (translated by Bezalel Naor):

Since it is impossible for our nation to attain its lofty destiny other than by actualizing these two components—the universalist symbolized by Joseph, and the particularist symbolized by Judah—there arise in the nation proponents of each aspect. Those who would enhance spirituality, prepare the way for Messiah son of David, whose focus is on the final destiny…Those who redress the material, general aspects of life, prepare the way for Messiah the son of Joseph.

Was Rav Kook comparing Herzl to a Messiah of sorts?

In a later letter that Rav Kook sent to his father-in-law, Rav Eliyahu Dovid Rabinowitz-Teumim, known as the Aderet, he distances himself from that interpretation—suggesting that there must have been some who saw it as such. “Of course, I spoke pleasantly and politely,” Rav Kook writes recounting his eulogy for Herzl, “but I did reveal the fundamental failure of their [the Zionists’] entire enterprise, namely the fact that they do not place at the top of their list of priorities the sanctity of God and His great name, which is the power that enables Israel to survive.” Rav Kook’s vision for Zionism, on the other hand, required a union of both Yosef and Yehudah.

It should be noted that Rav Kook was hardly the only serious rabbi to offer words memorializing Herzl’s passing. Rav Avraham Eliyahu Kaplan, one of the most cherished students of the Alter of Slabodka published an essay entitled “On Herzl” that is included in his work B’Ikvos Ha’Yirah. It is an appreciation to Herzl for fostering Jewish pride among the Jewish people. Herzl taught us, Rav Kaplan writes, how to say with pride, “I am a Jew!” The essay was recently translated by Rabbi Nathaniel Helfgot for the Hakirah Journal (vol. 34).

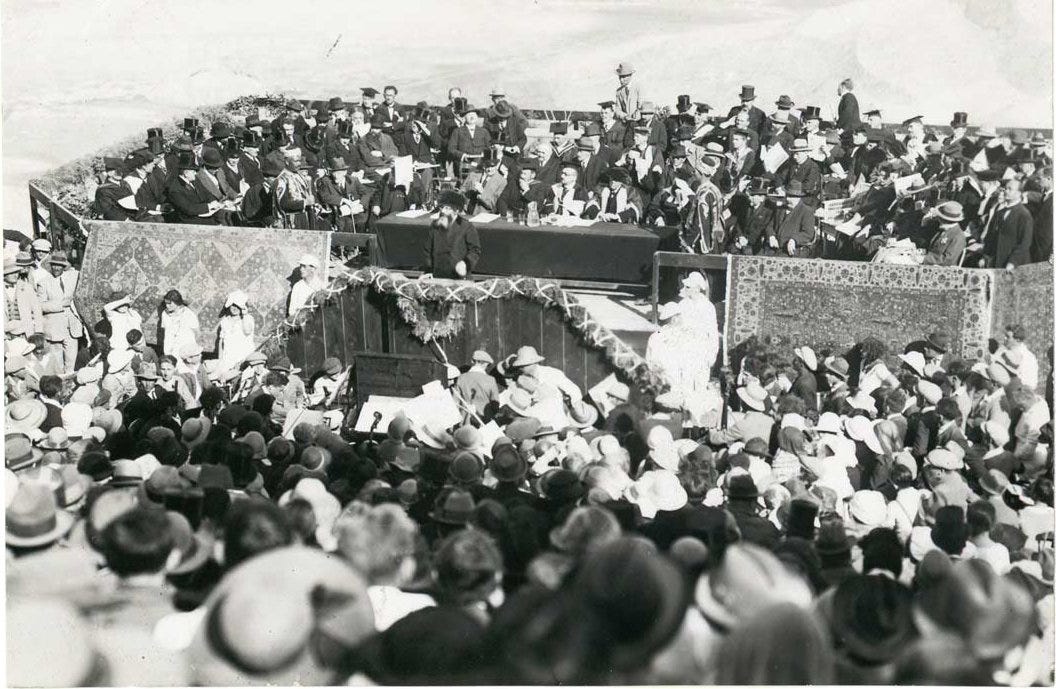

This was not the only public address to cause controversy for Rav Kook. In 1925, two decades after memorializing Herzl, Rav Kook gave the invocation at the inauguration of Hebrew University. Among the thousands present were Rabbi Hertz of England and the famed Israeli poets Bialik and Ahad Ha’Am. Lord Balfour himself spoke following Rav Kook.

Rav Kook invoked the verse, “Torah shall go forth from Zion,” a connection that many felt conflated secular studies with the value of Torah—a misunderstanding Rav Kook painstakingly followed up with colleagues to clarify.

Rav Yechezkel Sarna later remarked to Rav Moshe Tzvi Nerya that Rav Kook was only willing to speak at Hebrew University on the condition that they do not teach biblical criticism. Rav Kook was crestfallen when he later discovered they did, in fact, begin teaching biblical criticism at Hebrew University. Rav Kook’s student, Rav Yitzchak Hutner, described Rav Kook’s reaction upon learning this as “disappointment, frustration, and piercing pain.” Rav Hutner then self-reportedly remarked to his teacher, Rav Kook, “Evidently, in addition to knowing the roots of one’s soul (shoresh haneshamah), you must also know where the legs of the body actually stand.”

Rav Hutner’s remark, carefully researched by Rav Eitam Henkin hy”d in his book Studies in Halakha and Rabbinic History in a chapter entitled, “R. Hutner’s Testimony on R. Kook and Hebrew University,” in many ways cuts to the core of Rav Kook’s strengths and weaknesses. He was able to see past the exteriors and find the hidden sparks of holiness of Zionism at the roots of people’s soul—yet he sometimes underestimated the intractability of the present position in secularity. Rav Kook saw the unspoken but, as hard as he may have tried, was not always able to move the location on which people actually stood.

The ultimate reconciliation between Yosef and Yehudah still waits.

As Rav Kook explains in the memorial for Herzl, the union of Yosef and Yehudah—material and spiritual, universal and particular, will usher in the final redemption, each representing a different component of the realization of messianic times.

Until then, we only have the ambiguous forgiveness of the Torah. An apology through action that does not yet fully mend the inner spirit of the heart. They hug and kiss, but distance still remains in the recesses of their souls. Yosef grants this material reconciliation through action, as is Yosef’s essence, but the final reconciliation of the heart, the domain of Yehudah, still awaits.

They could stand together, to paraphrase Rav Hutner’s remark to Rav Kook, but the roots of their soul still await complete union.

Perhaps, in the moment we live today, we see the place where they stand and, most importantly, the roots of the respective souls of the Jewish people, slowly moving closer together.

Shabbos Reads — Books/Articles Mentioned

Rav Kook: Mystic in a Time of Revolution, Yehudah Mirsky

Orot, trans. Bezalel Naor

When God Becomes History: Historical Essays of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook, Bezalel Naor

“On Herzl” (1919) by Rabbi Avraham Eliyahu Kaplan, Nathaniel Helfgot

Rabbi Isaac Ha-Kohen Kook: Invocation at the Inauguration of the Hebrew University, Shnayer Z. Leiman

What’s the Truth about Rav Kook’s Hebrew University Invocation?, Ari Zivotofsky

Studies in Halakha and Rabbinic History, Eitam Henkin hy”d

Rav Hutner’s Testimony Concerning Rav Kook, Eitam Henkin hy”d

Check out All Parsha, where you can find weekly audio of Reading Jewish History in the Parsha, as well as other incredible presenters and amazing features that will enhance your Parsha journey!

Reading Jewish History in the Parsha has been generously sponsored by my dearest friends Janet and Lior Hod and family with immense gratitude to Hashem.

The translation for R Kooks hesped for Herzl can be found here:

https://www.machonso.org/uploads/images/13-D-10-lamentation.pdf

What was the story that R Ezra Neuberger told you about R Kook and The Alter? It sounds like it got cut off in the recording.

I would also take issue with the statement that R AE Kaplan said that Herzl was the one that taught us how to say "I am a Jew". R Kaplan clearly states that that was something that we where always able to say internally - Herzl was not the one to teach us Jewish pride. He was the one who taught us how to say it externally, when talking to the nations.

Thanks for this great show!

Wonderful devar Torah, Rabbi Bashevkin. I appreciate your close reading of the text in guiding us to the fact that the Torah is silent on the matter if Joseph formally forgave his brothers. Perhaps the Torah wants us to relate to the human condition that although Joseph and his brothers do hug and kiss, deep down Joseph was still hurt by their actions. I will share your devar Torah at my Shabes table.